- Share via

The dilemma arose just a few days before the book was set to go to press.

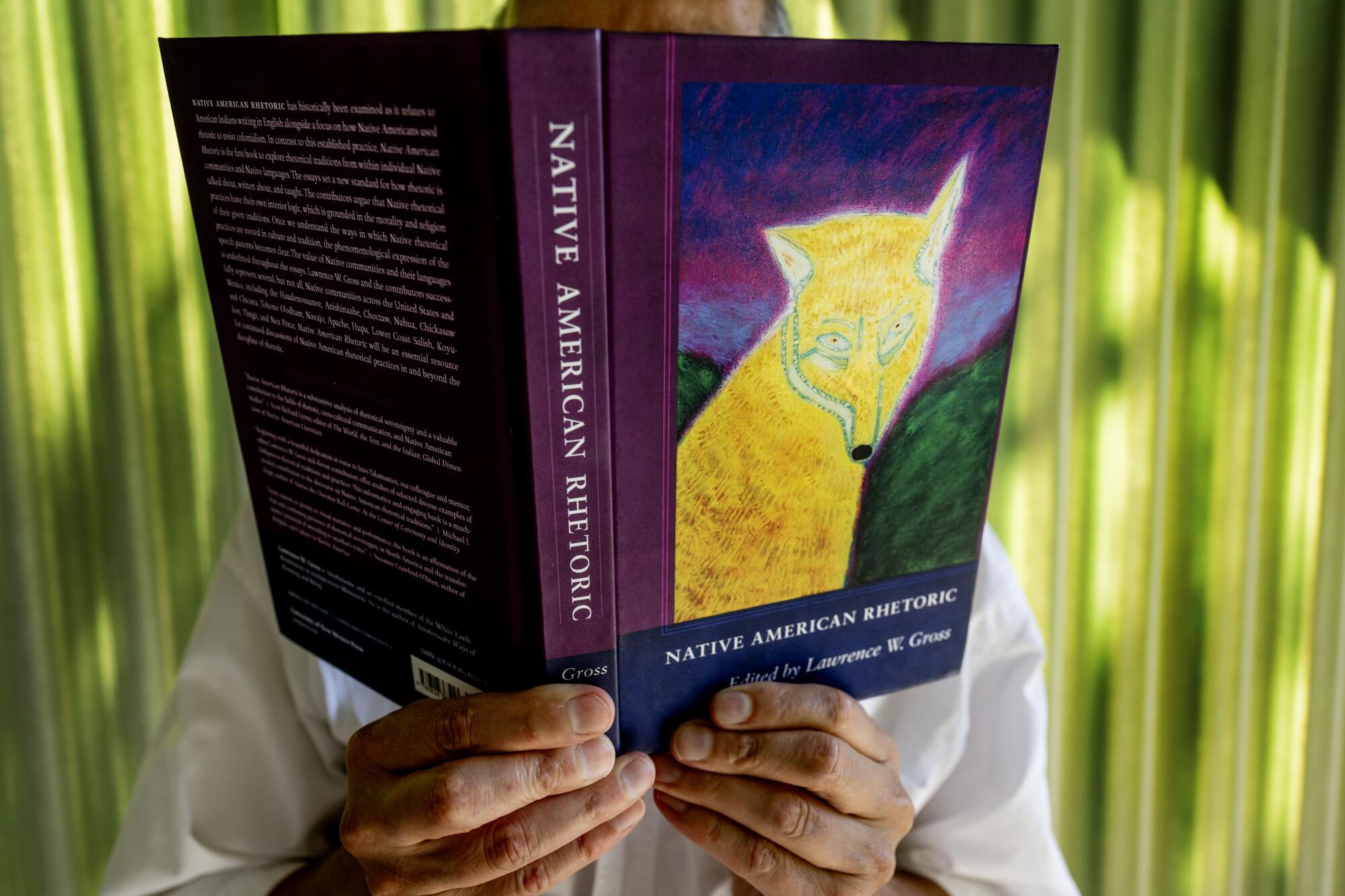

Two contributing authors confronted their editor, Larry Gross, an associate professor of race and ethnic studies at University of Redlands, who had worked for months to assemble the anthology, “Native American Rhetoric.”

The two authors wanted to talk to Gross about a fellow contributor to the book. As a classmate at UC Santa Barbara, she had always identified to them as white, the writers told Gross. But in the book she claimed ancestry from the Chippewa, Sioux and Crow tribes.

The matter, Gross recalled, was “of grave concern to me and caused me to feel alarmed. I did not want our book and the contributors to be ... tainted.”

With the book deadline bearing down on him, Gross, an enrolled member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, decided to conduct his own investigation of the graduate student’s background.

His inquiry would raise the larger questions that have come to loom over discussions of Native identity: What does it mean to be Native American? And who gets to decide?

After centuries of population declines, more and more people are self-identifying as Native American.

The number of Americans identifying as Native American alone or in combination with other races rose 86% in the 2020 census from the 2010 census.

The sharp increase is not due to a baby boom, but reflects people changing how they identify at some point during their lives.

“This population increase appears to be dominated by ... ‘racial shifters,’ individuals who have changed their racial self-identification on the U.S. census from non-Indian to Indian in recent years,” wrote Circe Sturm in her book “Becoming Indian,” which traces the population increase to at least 1960.

This influx has been met with some skepticism within Native American communities, fueling fears that those with limited or faked connections to tribal life might leach scarce resources and misrepresent Native beliefs or opinions.

In the 1970s and 1980s, such people were called Native American “wannabes,” said Kim TallBear, a professor at the University of Alberta and enrolled member of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Some “wannabes” claimed Native identity to secure federal or state resources, while others were seeking spiritual regeneration they associated with Native American communities. Others believed sometimes unprovable family lore about Native roots.

Back then, family stories were more difficult to trace.

In the decades since, at-home DNA testing and online genealogical records have helped many Americans discover or confirm Native heritage. The same tools, however, have also made it easier to reveal the opposite. Makers of meritless claims run the risk of being labeled “Pretendian.”

“People who started Prentendianism before advent of the internet probably never expected this level of data,” TallBear said.

Beyond concerns about scholarships and grants, fraudulent claims of Native American identity are inherently harmful to Native Americans, said Lianna Costantino, who runs the Tribal Alliance Against Frauds, an independent group that investigates allegations of ethnic fraud.

“A lot of us were doing genealogy and we were seeing how many unfounded unverified family myths are out there,” said Costantino, who is Cherokee. “Then we began seeing all the fraud that was being associated with it. People taking up space intended for Indian people. We decided we needed to do something about it.”

For those working in academia or media, allegations of ethnic fraud could jeopardize their career prospects.

Andrea Smith, a professor at UC Riverside, resigned in 2023 after battling allegations that she falsely identified as Cherokee for decades, despite not being enrolled in the tribe and not having clear family connections to it.

At UC Berkeley, Elizabeth Hoover remains a professor after apologizing last year for identifying incorrectly as being of Mohawk and Mi’kmaq descent.

The battles can be bitterly personal and confined to one academic institution, or they can play out on the national stage, as with Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

But there is no consensus among Native Americans on whether granular inquiries into individual identity are the correct way to deal with the problem.

In the years before the release of “Native American Rhetoric,” fellow graduate students at UC Santa Barbara thought they knew Alesha Claveria. She was a white woman passionate about Native American theater.

Delores Mondragon was teaching a Native American religious traditions class with Claveria while both were grad students in 2017 when something surprising happened after a class.

A student approached Mondragon, an enrolled member of the Chickasaw Nation, then decided to speak with Claveria instead.

“‘I’m going to talk with the other Native teaching assistant,’” Mondragon recalled the student saying.

Mondragon was caught off guard.

“I went up to Alesha and said, ‘When did you become Native?’” Mondragon said. “She says, ‘I don’t have time to talk right now.’”

The two went to one more conference together but never again addressed Claveria’s change in identification, according to Mondragon.

“I had already asked her in person and she hadn’t really responded. After that she avoided me,” Mondragon said.

Four years later, the two were working on submissions for Gross’ book, as was a third graduate student, Felicia Lopez.

When Gross shared the contributors’ biographies with the group, Lopez and Mondragon were shocked by how Claveria described her heritage.

“Her work is influenced by her mixed Chippewa, Sioux, Crow, and Norwegian heritage and by the peoples and places in and around Montana, her home,” she wrote in her biography.

That prompted an email by Lopez on June 11, 2021, to Claveria and the other book contributors: “Dear Alesha (and all), It has been about four years since we spoke at length about these kinds of things, but last I recall, you were exploring your family history via DNA and an ancestry service and had not found any Native relatives — just family stories. It looks like this has changed, and you now have three different Native communities! I know these journeys of recovery can be complicated, and I don’t want to speak without knowledge of the facts, but I hope you will share a little about what has motivated this change in self-identification. I look forward to your story of recovery and reconnection, and I wish you well. Best, Felicia.”

Claveria did not respond to numerous phone calls, texts or emails asking for comment for this story. But the day after Lopez’s email, she emailed Lopez and the other contributors.

“What you’ve written misrepresents me, and I don’t appreciate it,” she wrote.

In a separate email, Claveria addressed Gross directly.

“In including all the contributors and the publisher, [Lopez] has addressed me in a very public way and puts me in the position of having to answer for how I self-identify. This is hurtful as I have been open about both my family and cultural connections,” Claveria wrote. “Naming the part of my heritage that includes the nations of my ancestors as I have heard them named is one way I choose to honor and remember them.”

Indigenous identity can be complicated. It is something that people ascribe to themselves and something that tribes can confer onto people via enrollment or a certificate of degree of blood.

In the U.S., there are different ways by which people identify as Native American. The first and most unassailable is to be enrolled in one of the 574 federally recognized tribes. Each tribe determines its own enrollment, but a common requirement is lineal descendancy from someone on the tribal roll.

Others may not be enrolled, but have family members in a tribe and are accepted members of the community.

Still other Americans were displaced from their Native communities or reservations long ago — due to displacement or forced adoption programs — and are trying to rediscover their place in tribes.

Some don’t even need tribal ancestry for enrollment. Black people whose ancestors were enslaved by the Cherokee Nation can now apply for citizenship, the tribe’s top court ruled in 2021.

Others claim their ancestors made the difficult decision to pass as white to evade bigotry and anti-Native American laws limiting where they could live and their rights to own land.

Centuries of intermarriage, meanwhile, has resulted in millions of people with a small percentage of Native American ancestry.

A key to Native American identity, TallBear says, is being connected to a living community. It’s inherently relational between a person and a tribe — not something one can decide without recognition and acceptance from a community.

“You cannot connect to bones in the ground,” she said. “When you’re talking about five, six, seven, 20 generations back, there is nothing to connect to. You and your family have been socialized as non-Native.”

According to Jacqueline Keeler, an independent journalist and enrolled member of the Navajo Nation, it’s rather straightforward: “Were your ancestors subject to Indian federal policy? It should be in your immediate family. Your grandparents, your great-grandparents. That’s what affects you.”

For the record:

8:30 p.m. Feb. 23, 2024An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Jacqueline Keeler began her list in 2015. This update clarifies that the list was a Google Doc and that it was published in 2021.

Keeler has gained notoriety in some circles and respect in others for compiling an “Alleged Pretendians List,” which she first published in 2021 “to verify these people’s tribal claims.” Visitors to the Google Doc added 200 names, though it is not currently available for the public to view.

Critics of the list found its targets arbitrary and questioned Keeler’s intent and methodology.

“There’s not a clear process on how this research is being conducted or how individuals are singled out for suspicion,” wrote Angela Newsom in a post on Pow Wows, a website with articles and information about Native communities.

“These decisions should ultimately be made by the tribes/communities in question and not by any self-appointed arbiter of Indian identity who isn’t a member of all of the tribes in question,” a group of writers argued in a public letter on the website “Last Real Indians.”

Andrew Jolivette, an enrolled member of the unrecognized Atakapa-Ishak tribe from Louisiana and director of UC San Diego’s Native American and Indigenous Studies program, helped draft the open letter. He said that Keeler’s focus on federal recognition of tribes in itself contributes to a “colonial framework” that defines what it means to be Native American.

Why, Jolivette wondered, should a person have to be part of a tribe recognized by the government — a colonial government that disenfranchised them — in order to prove their identity?

His public opposition to the list resulted in him being the focus of one of Keeler’s investigations.

Bridget Neconie, a member of the federally recognized Pueblo of Acoma in New Mexico, said her stance on who can be considered Native American has softened in recent years.

Neconie used to work in the admissions office at UC Berkeley, where she changed the system so students had to send as proof a federal tribal enrollment number if they identified as Native American.

But since leaving higher education, she has broadened her view to be inclusive of those in state-recognized tribes or non-recognized tribes.

“There’s a lot more to be said for state recognized, not recognized or mixed race people,” Neconie said. “I think there’s room for everybody.”

The investigations start with an allegation: Someone who claims to be Native American is not.

Generations of family history are typically dredged up through Ancestry.com. Investigators also can ask a tribe if a person is enrolled or has family enrolled.

That’s what Gross, the book editor, did. He bought an Ancestry.com account, made spreadsheets and emailed tribes about Claveria. After a weekend of digging, Gross was unable to find proof that Claveria — or any of her family members — had Native American ancestry.

According to Ancestry.com records reviewed by The Times, her grandparents were all listed on draft cards and census documents as white, as were her great-grandparents. Gross traced some family back to Norway.

Gross got a letter from the Crow Nation in Montana stating that Claveria is not enrolled. The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana also said they had no Alesha Claveria on the rolls, nor did her parents have any affiliation with the tribe.

The Chippewa Cree Tribe of Rocky Boy Montana also denied that Claveria was enrolled. The Fort Peck Sioux Tribe also said she was not enrolled or eligible to be enrolled.

It’s possible Claveria’s family and ancestors identified as white on official documents but were actually Native American. But Gross said that, based on the information he collected, he had not seen evidence of Native American heritage.

The issue, Gross said, was not Claveria’s ancestry, but her biography, which he considered a violation of academic ethics. Gross said Claveria never provided him “credible evidence” of Sioux, Chippewa and Crow ancestry, beyond saying her grandmother said she was a part of those tribes.

Her grandmother, Marion Gerrish, in an interview with The Times, said her father-in-law was “half Chippewa Cree.”

That man would be Claveria’s great-grandfather, Wilfred Chester Noice, who is listed as white in the 1940 U.S. Census.

Gross said that family stories alone are insufficient evidence of Native American identity.

He decided to remove her chapter from the book.

“I would advise Alesha to be careful with making claims of being of Native heritage,” Gross wrote in the June 14, 2021, email to all contributors to the book. “If she is not Native, she can still be a very powerful ally for Native people. There is still time for her to give up any false claims of being Native before they potentially damage her career.

“If she is of Native descent, she needs to be prepared to provide better evidence of her Native heritage than I could find. I am trying to be supportive of Alesha here. I hope she will take my advice in the spirit it is intended.”

Some contributors celebrated the decision in emails to Gross.

“Thank you for doing this difficult work Larry. I consider it [to] be work on the behalf of the volume, all of us who are contributing authors, and to the profession,” said Philip Arnold, a professor of religion at Syracuse University, who is not Native American, though his wife and children are Iroquois.

But Gross’ decision had at least one detractor — another contributor to the book.

Margaret McMurtrey, a graduate student at UC Santa Barbara, who is an enrolled member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, said she was “disappointed” in Gross’ response. McMurtrey is part of leadership in the university’s Native American and Indigenous Collective.

“From what I understand Alesha was not given an opportunity to share her family history with Larry,” she wrote in an email to contributors. “The assessment that Larry has made is of course his prerogative as the editor; however, I believe it is short sighted and participates in character assasination [sic] of Alesha regarding her identity, integrity, and scholarship. Larry you have contributed to a campaign of slander and identity policing that I find abhorrent. I am deeply disappointed in your process and handling of this matter.

“For me the situation is intolerable and I can no longer in good conscience be a part of this collection and by remaining in the collection appear silently to condone these collective actions.”

McMurtrey asked that her chapter be removed from the book.

“I do not want to be affiliated with a publication which perpetuates the settler state and contributes to the historical trauma imposed upon Native Peoples of the Americas,” she wrote.

“In Alesha’s case ... I believe that she acted in good faith,” McMurtrey told The Times. “I don’t believe she ever was trying to mislead people.”

McMurtrey does not support genealogical investigations into Native-ness and believes they allow laymen to attempt to determine whether people are too white.

“Is that the way a Native person would approach this? It contributes to dividing communities. That person is and that person isn’t. To me, we’re doing the colonizers’ work for them. That was the plan all the way back to Jefferson. Let’s get them marrying white people so they eventually have no bloodline left,” McMurtrey said.

The book, “Native American Rhetoric,” was released in 2021 — sans chapters from Claveria or McMurtrey.

It is unclear whether Claveria continues to identify as Native American. She got a job teaching at Cal State Northridge in 2022 and her bio does not say anything about her background. A school spokesperson said that, by law, it cannot consider a job applicant’s ethnic background.

“CSUN does not seek or discuss such information with job applicants,” said Carmen Chandler, the spokesperson, noting that allegations of Pretendianism are “incredibly complex and are case-by-case specific.”

The year she joined CSUN, Claveria published her doctoral thesis on Native North American drama and thanked “the elders” and “the ancestors.”

“Thank you for doing what it took so that we could have life,” she wrote in September 2022.

A few months later, Claveria was on a panel at UC Santa Barbara about Thanksgiving and was asked twice by a student moderator about what Thanksgiving was like growing up Native American. She did not answer the question directly either time.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.