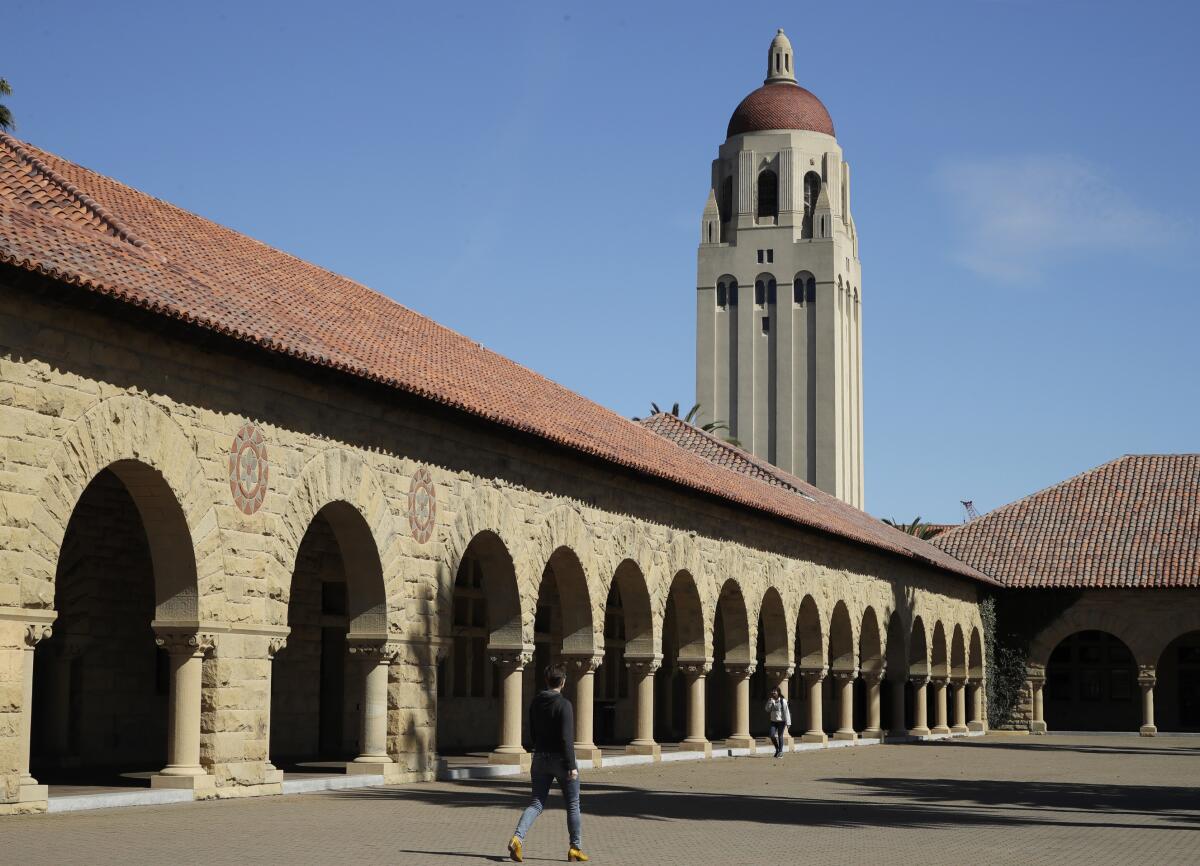

California effort to crack down on legacy and donor admissions could hit USC, Stanford

- Share via

As scrutiny over fairness in college admissions intensifies, a California lawmaker renewed efforts Wednesday to ban state financial aid to private campuses — including USC and Stanford University — that give admissions preferences to children of alumni and donors.

Those preferences, known as legacy admissions, have come under growing attack following the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling last June striking down race-based affirmative action in cases involving Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Critics say legacy admissions disproportionately favor affluent applicants — most of whom are white — and should be eliminated, just as race was banned in deciding who gets access to the nation’s most selective colleges and universities.

“We want to make sure that every student applying into the most elite schools in our state have an opportunity, that it’s fair, that it’s equitable,” Assemblyman Phil Ting (D-San Francisco), said Wednesday as he unveiled his new bill at a Sacramento press conference with equity advocates and two Stanford students.

USC, Stanford and Santa Clara University are the largest providers of legacy and donor preferences in California, according to annual data they submitted to the state for the last four years.

The University of California and California State University systems do not give preferential treatment to children of alumni and donors, and some private institutions, such as Occidental and Pomona Colleges, have dropped the practice in recent years.

The bill, AB 1780, would prohibit colleges and universities from participating in the Cal Grant program if they provide preferential treatment in admissions to an applicant related to a donor or alumni. The Cal Grant program provides financial aid covering full tuition and fees to qualified financially needy students at UC and CSU and some support for students at private institutions. Some living expenses are also provided on a limited basis.

USC accepted 1,740 applicants with legacy or donor connections, or 14.4% of the fall 2022 admitted class, according to data submitted to the state. Of those, 96% were relatives of alumni and nearly 4% were connected only to donors. Stanford offered admission to 287 students, or 13.8% of the class — with 92% related to alumni and 8% with ties only to donors.

A chaotic rollout of a new federal financial aid form is roiling high schools and upending college admissions, impeding students from filling out the all-important FAFSA form.

Santa Clara admitted 1,133 students with alumni or donor connections, representing 13.1% of the class. Four other campuses that used preferences did so more sparingly, amounting to 1% to 3.6% of the fall 2022 admitted class. Their data were not disaggregated for alumni and donor-only connections in the Assn. of Independent California Colleges and Universities’ report to the state.

Stanford has not yet taken a position on Ting’s legislation, said campus spokeswoman Dee Mostofi. She said Stanford uses a holistic admissions process that considers legacy status as one of many factors as it seeks to enroll students who contribute “diversity of thought, background, identity, and experience.”

Stanford students received $3.2 million in Cal Grant support for 2022-23, Mostofi said, compared with $263 million in total institutional aid. She added that the campus has expanded support for lower and middle-income students in recent years, including full coverage for tuition for students with family incomes up to $150,000. Additional aid covers room and board for those with family incomes of $100,000 or less. In 2018, Stanford removed home equity from financial aid calculations.

USC also has not taken a position on Ting’s legislation. In a statement last year, USC said it was deeply committed to diversity, with 1 in 5 admitted students from low-income backgrounds or the first in their families to attend college. The campus said then that all admitted students met high academic standards and were reviewed in a holistic process that “values each student’s lived experience, considers how they will contribute to the vibrancy of our campus, thrive in our community, benefit from a USC education and fulfill the commitments of our unifying values.”

Santa Clara University did not provide responses to questions.

According to state data, 2,972 USC students received $26.6 million in Cal Grant financial aid in 2021-22. At Santa Clara, 507 students received nearly $4.6 million, according to the California Student Aid Commission.

Such funding could be jeopardized if Ting’s bill succeeds. The Assn. of Independent California Colleges and Universities had opposed his earlier bill, saying it could deprive low-income students of needed financial aid.

Ting said campuses that continue legacy admissions “have plenty of money to continue to offer those students scholarships, and they should offer the students scholarships.”

Two alums who fought for ethnic studies as student protesters in the 1960s have donated $10 million to the UCLA Institute of American Culture, the largest such gift, to endow posts in Asian American, Black, Chicano and Native American programs.

The high court ruling against affirmative action and new research have changed the national climate around legacy admissions, which could improve the legislation’s chance of passage compared with an unsuccessful attempt in 2019, Ting said. That earlier bill was later amended to require private institutions to annually report to the state their data on legacy admissions and was signed into law.

Ting noted that a Harvard study last fall found legacy admissions was a major factor in why Ivy League and other elite universities were more than twice as likely to admit students from high-income families — those in the top 1% earning more than $611,000 — compared with less-affluent peers with comparable standardized test scores.

Legacy applicants were admitted at higher rates at all levels of parental income, but the biggest boost was awarded to those from families in the top 1% of income earners, who were five times more likely to be admitted to the eight Ivy League campuses along with the University of Chicago, Duke, MIT and Stanford, according to the study.

The findings were “fairly shocking even for me, who obviously knew that folks at higher income level get an advantage,” Ting said.

Just days after the high court’s affirmative action ruling, three civil rights groups filed a complaint against Harvard with the U.S. Department of Education. The groups alleged that Harvard’s preferential policy for undergraduate applicants who are related to alumni or donors overwhelmingly benefits white students at the expense of students of color, violating federal law banning racial discrimination.

The complaint asserted that nearly 70% of Harvard applicants with family ties to donors or alumni are white and are about six times more likely to be admitted than other applicants.

Sophie Callcott, a Stanford senior, said Wednesday that legacy was factored into her admission because she is the daughter of two Stanford alumni, but she wants the practice to end.

“I do not want my achievements to be overshadowed or questioned by the possibility that I only got into Stanford because my parents went there,” she said at the news conference. “I also recognize that abolishing legacy admissions is one critical step to take on a larger path towards equitable admissions and higher education across the board.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.