Metro advances rail extension in the South Bay, and not everyone is happy

- Share via

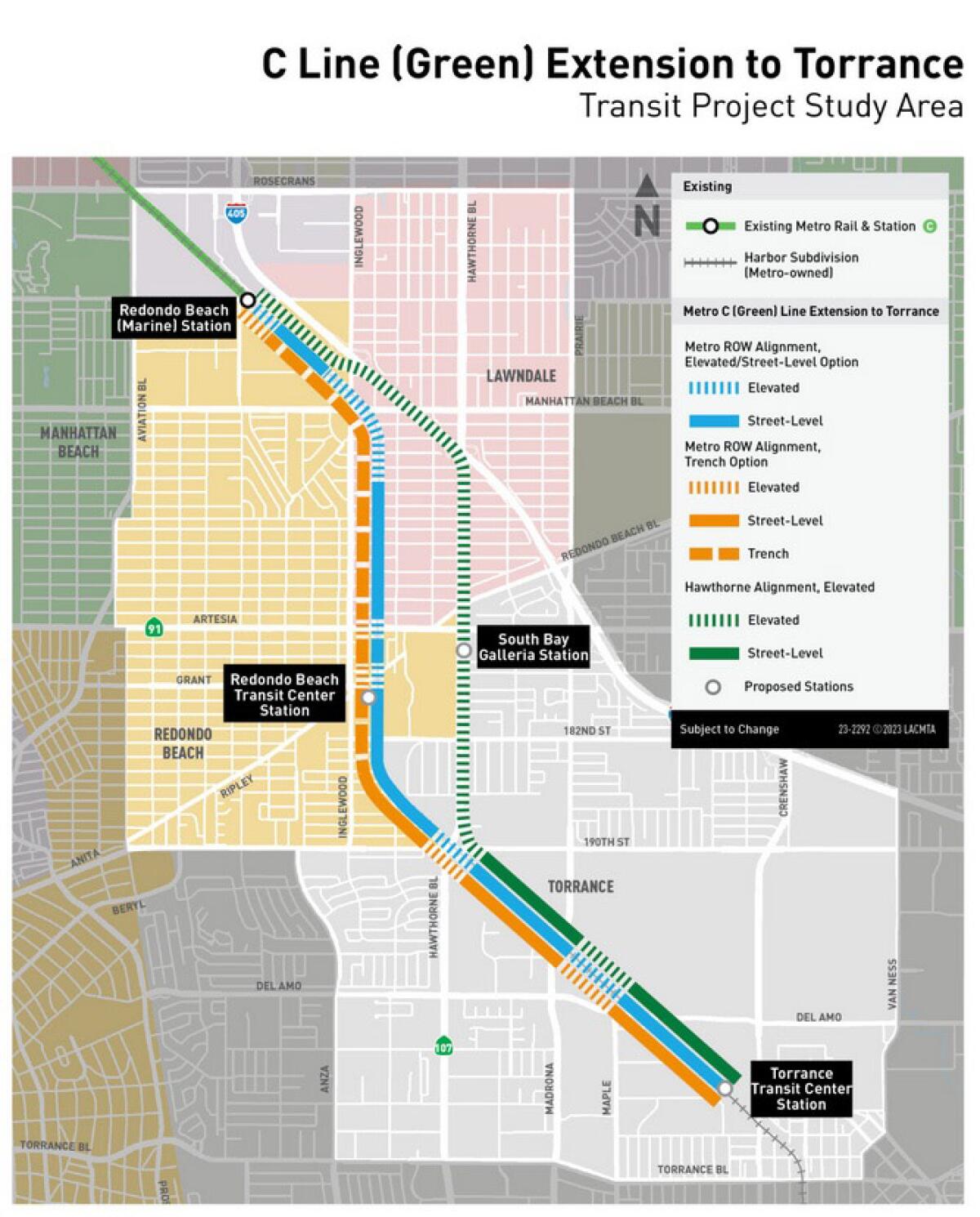

Metro board members advanced a two-stop, 4.5-mile light rail extension of the C Line through the South Bay on Thursday, while leaving an opening to reverse course, as many residents voiced opposition to the plan.

Residents of Redondo Beach and Lawndale packed in at a Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority board meeting, asking the nine members present to vote against a route that would run along a rail right-of-way behind homes, known as ROW. Many wore red shirts that said “No to Row” and pushed for a more costly path that would draw more riders down Hawthorne Boulevard, where the old Pacific Electric Railway Red Cars once ran.

After more than two hours of public comment on both sides, the board unanimously gave the green light to further environmental analysis of the ROW route, a crucial step to developing the project. The route was backed by Metro staff because it would cost $800 million less and because it took advantage of already existing transit stations in Redondo Beach and Torrance. Advocates that want to see denser housing and more transit also backed it, as did the city of Torrance.

But the approval came with a caveat, introduced by board member and Inglewood Mayor James Butts, who represents the region on the board: The agency has to come up with refined cost estimates for both routes and an exploration of funding sources, and study issues raised by community members during the recent environmental process. Those include vibration from trains, proximity to homes, moving of jet fuel pipes that run near homes and any residential displacement.

“The game is not over,” Butts told the crowd, which was clearly deflated by the vote. “What this means in essence is that we live to fight another day.”

Lawndale and Redondo Beach warned they would explore legal options should the ROW route move forward.

But the action by Butts offered some reason for optimism.

“This will shed some light on how much it’s going to cost to relocate those fuel pipes or protect them,” Redondo Beach Councilmember Zein Obagi said after the meeting. “That potentially could really push the budgeting of those projects.”

Expect to wait for help if you crash in the desert on Interstate 15 from Los Angeles to Vegas. There’s only one fire station dedicated to the stretch. Last year, the five-person crew answered nearly 1,000 calls.

Although the decision, decades in the making, is not final, it paves the way for final environmental clearances necessary to build. Those studies can take more than a year and seldom are dashed, making a course reversal unlikely.

Still, Supervisor Holly Mitchell said that “this isn’t the end of the process” and pointed out that Metro has previously ditched projects — pointing to the reversal of the 710 Freeway expansion.

Mitchell, who represents the South Bay, had earlier delayed the vote and made efforts to find available funds. She said next time the project returns to the board, she expects to see details of how the project can be paid for and what kind of community improvements it will include.

Estimated to cost roughly $2.23 billion, the project is one of several ambitious rail projects the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority is undertaking in the coming years. It has stirred an emotionally charged debate in the region over where rail lines should be, what it will mean to the communities they traverse and how Metro addresses residents’ concerns. The line, while extending off what is now the C Line, will eventually be a segment of the yet-to-be-completed K Line, creating an even more complex transit network.

“It’s just exhausting,” said Niki Negrete-Mitchell, who owns a Redondo Beach home along one of the proposed routes and has gone to dozens of meetings to voice her opposition. “It’s killing me. If this thing were to happen ... I personally would need to be relocated.”

Negrete-Mitchell, 65, is one of the hundreds of residents who live along a freight rail corridor Metro purchased in 1993 when the specter of rail expansion began to take shape. For years, she said, only one train a day would pass by. Neighbors would use the corridor to let dogs run and take walks. There was even talk about making the land into a parkway. Many like Negrete-Mitchell, who bought her home 16 years ago, didn’t know or grasp Metro’s plan. When she went to her first community meeting, she was in disbelief.

Since then she has been part of a group of residents who have dogged the agency, attending public meetings to argue that its assessments don’t paint the full picture of the challenges the route poses behind homes. The group said they have gotten more than 1,500 signatures of residents opposed.

The chosen extension proposal runs along a BNSF freight corridor. If built out for Metro, passenger rail cars would run all day long between the Redondo Beach (Marine) station and a newly built Redondo Beach Transit Center, with a southern terminus at the Mary K. Giordano Regional Transit Center in Torrance. Neighbors complain that the corridor is too narrow.

Metro’s staff argues that a configuration of that route, putting a rail line alongside freight tracks, while adding grade separations near elementary schools at 170th and East 182nd Streets, is the most cost-effective and least disruptive of the different options considered. Torrance supports the choice, but the Daily Breeze reported its City Council is divided.

“We understand the concerns of noise to adjacent community along with safety concerns,” Torrance Mayor George Chen told a Metro committee considering the item ahead of the vote. The ROW path, he pointed out, leverages the millions in funding the region has sunk into two transit stations recently opened, one in Redondo Beach and the other in Torrance, that will feed into rail.

Negrete-Mitchell and residents near the corridor disagree. They fought for another route, an elevated path down a median of Hawthorne Boulevard, a six-lane Caltrans-owned state highway that runs both through Torrance and Lawndale.

The line runs from the Redondo Beach station and cuts across the 405 Freeway before heading south down Hawthorne Boulevard. That route would take it to a station near the South Bay Galleria before arriving at the same endpoint in Torrance. The owners of the plaza support that route and plan on building housing near the route. But staff reports show it would cost nearly $3 billion.

“This is infrastructure that’s going to be here for the next 100 years,” said Redondo Beach Mayor Jim Light. “You want to build it right, not fast and cheap. We should be doing it to maximize ridership.”

These are arguments the agency will continue to contend with as it builds more rail, said Ethan Elkind, who a decade ago published the book “Railtown: The Fight for the Los Angeles Metro Rail and the Future of the City.” When rail was being built in Los Angeles in the ’80s and ’90s there was a rule of thumb, you didn’t want to build in areas with more than 50% homeownership rates because residents would have the resources to push back and fight against the rail lines coming through.

The pushback from cities can tie up projects. “The issue is so hyperlocal,” Elkind said. “It’s kind of an insane system that we have. You’re basically asking for dysfunction when it’s so decentralized, and there’s so many veto points.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.