Pricey camps. Family favors. Early dashes from work. How do parents survive summer?

- Share via

Kristen Dang’s tenuously planned child-care schedule is in full summer swing — a costly, worry-inducing logistical feat that has tested her maternal prowess. And she considers herself among the fortunate.

She nabbed a coveted six weeks of camp for her soon-to-be 9-year-old son, Brady, at the Reseda Recreation Center. Back in March, Dang’s husband waited three hours in line to secure an $80-a-week spot in the L.A. Department of Parks and Recreation program.

The two weeks they were shut out at the park will be filled with surf and baseball camps, but those take up only part of the work day and cost a stinging $900 total. Pick-up and drop-off schedules vary day by day as the parents juggle work schedules.

Come August, Dang must fill two empty weeks. Grandma will step in for one. Then Dang likely will take Brady to work with her at a private school’s IT department.

“Financially, it just is so hard,” Dang said. “I feel like some of these camps take advantage of the fact that parents … don’t have another option.”

Dang’s situation reflects the patchwork of summer camps, friendly favors, time off and leeway at work that parents weave together — often at a high cost. Two-thirds of children under 12 in California live in a household where all parents work, according to 2022 data.

The stress-provoking scramble is compounded by high demand and inflation that have pushed summer care expenses to an all-time high. A week of camp costs $530 on average in California, up nearly 18% from 2022, according to data from camp marketplace ActivityHero.

And unless money is no object, options are often scarce. Free and low-cost programs provided by school districts and cities aren’t open to everyone, and spots are limited. Plus, drop-off and pick-up times can vary at camps, upending schedules as parents figure out whether they can dash out of work a bit early or rely on friends for help.

“There’s this very obvious gap between what working families really need for their kids and the kinds of services that we have available to them,” said Hailey Gibbs, senior analyst for early-childhood policy at the Center for American Progress. “And we all sort of collectively shrug our shoulders and say, well, they’ll figure it out. And it really just doesn’t work that way.”

Engage with our community-funded journalism as we delve into child care, transitional kindergarten, health and other issues affecting children from birth through age 5.

Cost has been a big barrier for Marisa Pizano, who reduced her summer course load at Cal State Channel Islands and switched to online classes in order to care for her three children. The preschool her twin daughters attend is closed during the summer months. Summer school at her son’s Fillmore elementary campus ends at noon and doesn’t span the full break.

Even now, in these first weeks of July, Pizano, 24, remains on the wait list at Child Development Resources of Ventura County, a nonprofit that helps connect families with child care, in the hopes of receiving a state voucher meant to supplement the cost of summer and after school care for low-income families. Last time, her oldest son aged out of the program before Pizano was able to secure help.

“It’s a huge process but nearly impossible, it feels like,” said Pizano, who recently attended a Zoom session with more than 200 other parents near the top of the wait list.

Parents can choose from an assortment of early childhood programs, ranging from child care to preschool to transitional kindergarten. Here’s what they offer.

Parents often must braid together care arrangements they consider to be of less-than-ideal quality, which can make things even more difficult, Gibbs said.

And how a child spends the months-long summer stretch can affect academic outcomes, according to American University professor Taryn Morrissey, who studies public policies for children and families.

“It has short-term repercussions in the classroom come September, but it also has long-term repercussions for educational attainment,” Morrissey said. “It certainly seems that children are spending their time in really different ways based on what their families can afford.”

Find expert tips, must-read books and local resources to help your child get hooked on reading.

Summer relief in California

California public schools have received additional state funding since 2021 to help close the affordability and access gap surrounding summer care programs. At districts such as LAUSD and San Diego Unified, many students can now paint, play soccer, surf, learn guitar or visit the zoo for free or low cost.

The state gave districts until September to either use or lose the funds they have been allocated so far, money that must be spent on care that prioritizes students who are low-income, English learners or in foster care.

More than 1,600 districts, charter schools and county education offices are taking advantage of the $4 billion in Expanded Learning Opportunities Program funding to offer 30 nine-hour days of programming when school is not in session for students in transitional kindergarten through sixth grade, according to the California Department of Education.

Deciding between preschool and transitional kindergarten isn’t easy for parents. Here’s how eligibility, structure and academic environment may differ.

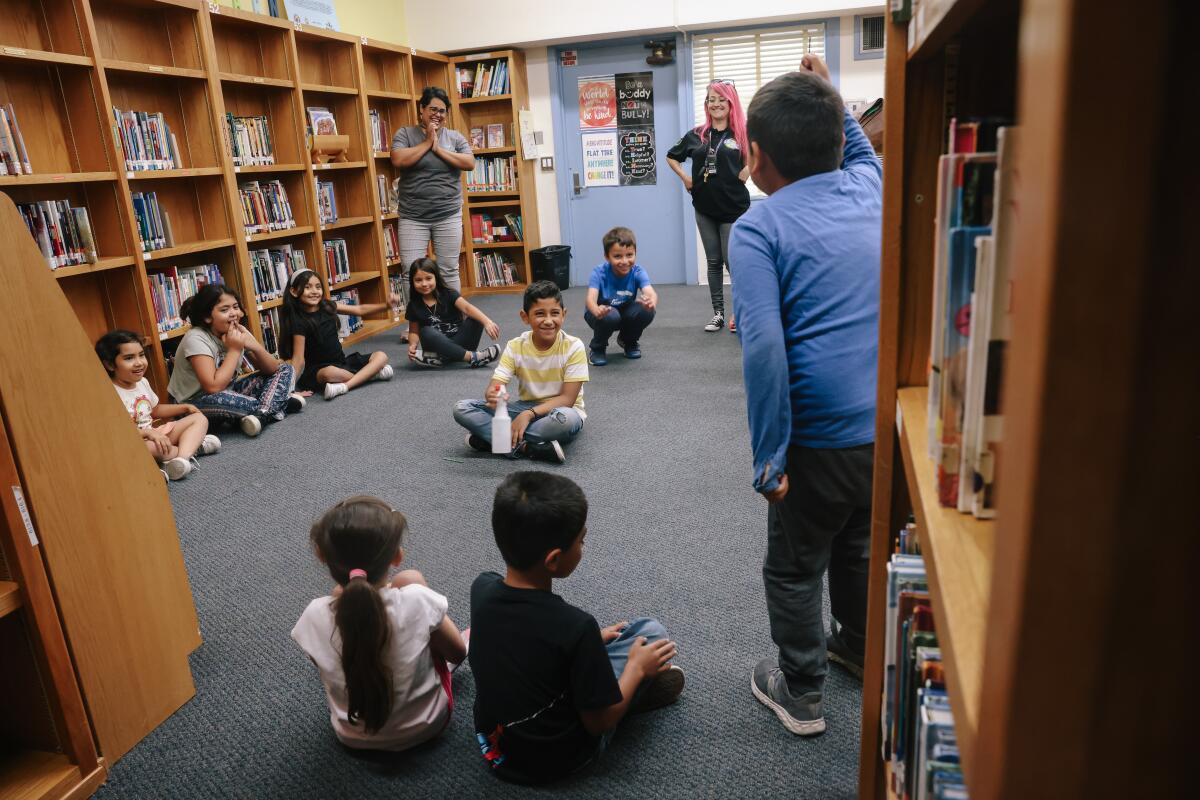

Some have chosen to partner with community organizations to provide further summer learning and enrichment opportunities both on and off school campuses. Woodcraft Rangers, which partners with LAUSD as well as other districts and charter schools across L.A. County, has seen exponential growth because of the funding, expanding from a few hundred participants in 2018 up to 5,000 students this summer, according to Chief Executive Julee Brooks.

Being able to rely on the free programming has been a huge help for Karen Gayles of Baldwin Hills, whose son attends a program run by Woodcraft Rangers at 99th Street Elementary in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Every day, the incoming first-grader plays basketball, runs around the track and spends time in the library. Gayles can drop him off as early as 7:45 a.m. and pick him up at 6 p.m., without having to change her schedule.

“I really, really love the vibe,” Gayles said. “They’ve been extremely patient with him.”

But the program runs only until July 26. School starts on Aug. 12. Gayles will likely rely on her parents to step in.

San Diego Unified has addressed the need for additional care by using Expanded Learning Opportunities Program funds to keep some camps going until the week before school starts. But the wait list is 400 students long.

Only districts with a high proportion of underserved families — which includes LAUSD — must guarantee a spot in the expanded learning program to all students. San Diego Unified is considering testing a low-cost option next year to expand beyond the underserved families it’s required to prioritize.

‘It’s just a mess.’ The race to secure subsidized child care

Thousands of L.A. families are desperate for low-cost alternatives. But spots at subsidized camps such as those run by the parks department aren’t easy to secure. This year, the camps are serving 6,300 kids per week across 124 recreation centers. Families earning less than $91,000 pay a subsidized rate of $25 per week for each child at select sites. Families who make more can still secure a spot, but at slightly higher rates, said Chinyere Stoneham, the assistant general manager of the recreational services branch.

This year — like most years — the website crashes on sign-up day. That’s why Dang’s family took no chances and went to the park to register in person, despite the hours-long line.

Because of website confusion, Rachel Ceasar couldn’t secure all of the spots she wanted. Her daughter ended up on a wait list this year, causing Ceasar to pay $250 for a more expensive camp. By the time she got off the wait list, it was too late.

“It was, it’s just a mess,” Ceasar said.

Nabbing spots in summer programs run by the Boys and Girls Club isn’t easy either, according to one Canoga Park mother who works as a nanny but struggles to find care for her own child. She asked that her name not be used to protect her privacy. She was relieved that her daughter, who turns 11 this month, got preference when enrolling in the free program run through LAUSD since she had participated in it before.

Many parents allow children more than double the TV and tablet time experts suggest. Families are turning to screens for learning and distraction, clashing with advice.

When camp concludes at the end of July, she will take a few unpaid days off. Then her daughter will likely spend some time both at her former daycare — where she’ll be the oldest child — and at home alone while the mother keeps an eye on her through security cameras.

“You figure out whatever you can do to handle it, and it is what it is,” the mother said. “We’re basically grasping at straws because there aren’t that many programs available.”

This article is part of The Times’ early childhood education initiative, focusing on the learning and development of California children from birth to age 5. For more information about the initiative and its philanthropic funders, go to latimes.com/earlyed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.