‘Inu-Oh,’ a tale of cutting-edge artists in ancient times, is like nothing you’ve seen

- Share via

“Inu-Oh,” the animated film depicting 14th century Japan, starts conventionally with the look and exposition one might expect of such a venture. After all, it’s adapted from Hideo Furukawa’s historical novel “Tales of the Heike: Inu-Oh,” set during a period of warring clans in the 1300s. Still, there are hints early on that this won’t be like other period epics: It focuses on biwa priests and Noh performers. There’s a fleeting glimpse of a baby born impossibly deformed. And a mystical accident leaves Tomona, a fisherman’s son, fatherless and blind.

Then things get crazy.

Visionary animation director Masaaki Yuasa says through an interpreter, “The turning point, going from traditional to unconventional, is when Inu-Oh [a Noh performer] and Tomona meet. From there on, a lot of strange things happen, unexpected things. Things get innovative.”

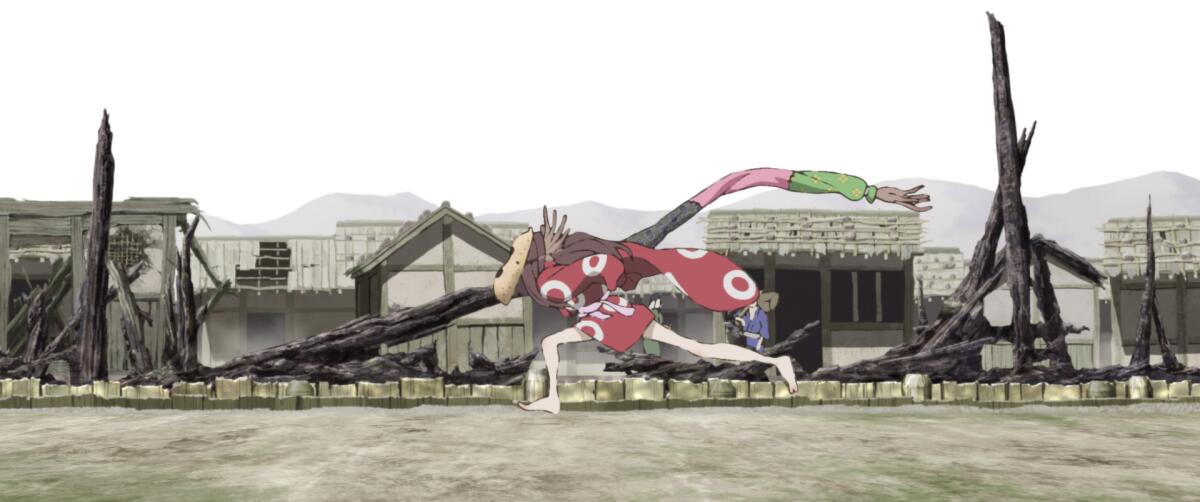

The maker of “Lu Over the Wall,” “The Night Is Short, Walk on Girl” and “Ride Your Wave” isn’t kidding. Blind Tomona grows up to become a biwa priest (playing a Japanese instrument much like a lute, singing traditional stories of the Heike clan). As he learns of a series of murders of biwa players, he makes the acquaintance of Inu-Oh, the now-grown child of a Noh performer with bizarre abnormalities including scaly skin, a third arm and an extremely elongated right arm. The two hit it off.

What follows is a burst of unhinged imagination by the filmmakers and creativity by Tomona and Inu-Oh. The outsiders become wildly popular with wild new performance styles that get them in trouble with the establishment. How ahead of their time are they? Audiences of “Inu-Oh” might recognize some Michael Jackson-esque dance moves in their new Noh and some acid-rock vibes in their impassioned grooves. And as their performances become more and more magical, Inu-Oh evolves as well.

“I wanted Inu-Oh to be totally high-tension, a lot of movements from athletes, gymnasts, jumpers and kung fu stars like Jackie Chan. Then he would gradually get more and more elegant as he becomes more human,” says Yuasa.

“For Tomona, I wanted him to be one of those performers that would die at 27. I modeled him after Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix. A huge star, like the Beatles. And I wanted to put in some elements — body exposure — sexy elements, too.”

If this sounds bizarre, it is — in the best way. It’s not just the music that is unexpected; the performances are kaleidoscopic riots of color and unexplained pyrotechnics.

“I think maybe some crazy music was around then, in the 14th century. But maybe it was too crazy; nobody wanted to talk about it. The performers, to live, to survive, they had to have the audiences, so they were performing like they could die. They were taking all these risks. Maybe the people back then, when they saw Inu-Oh, it was total astonishment, it was eye-opening. I exaggerated so people watching the movie would be astonished as well.”

But isn’t this a historical film? Sort of. There really was a Noh performer named Inu-Oh, and he shows up in some contemporary accounts. He apparently performed for the shogun and the emperor of the time. But though he was apparently extremely popular, nothing of his work has survived.

“Inu-Oh has a name in history, but nothing else — no record of his performances or what he wrote. Zeami [the most famous Noh artist of the day] had in his act one short sentence saying that Inu-Oh was a very elegant performer and he was influenced by him. [Novelist Furukawa] and I thought, ‘He was really popular, even more popular than they were, but there’s no record of what he did. Why? What was he like?’ That was our inspiration.”

In the imagination of the filmmakers, it’s as if we were handed down the works of Marlowe or Salieri and told they were the great masterpieces of the day, while records existed of someone named Shakespeare or Mozart but their art was lost forever.

Beyond the story of artists running afoul of the powers that be is one of a bond of deep friendship, a kinship that transcends literal logic. It’s expressed in the film’s beautiful and surreal ending, which feels right in line with its flights of fantasy.

All of which has the effect of making it feel immediate today. Yuasa says the art of Noh isn’t particularly popular in his country anymore, but “in the 14th century, everybody loved it, everybody was crazy about it. It was really influential to everybody in the villages, everywhere in Japan. For me, the rock and roll from the ‘60s and ‘70s, it had that same kind of impact.

“If you have no knowledge of Japanese history, that’s OK by me. What’s most important is that audiences enjoy the songs and dance and music just as the people 600 years ago in the film — so the experience is like being at a concert.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.