How the coronavirus will change book publishing, now and forever

- Share via

On Monday night, the literary agent, editor and publisher Andrew Blauner sent his contacts a PDF of “The Patient’s Checklist” by Elizabeth Bailey. The book is currently out of print, and with no digital copies available, Blauner wanted people to have access to the text should they fall ill and have to go to the hospital. “You can send this version to anyone you’d like, anyone you think might be helped by it. It’s the book which [doctor and author] Atul Gawande said ‘could save your life.’ ”

Blauner is just one member of the homebound publishing community still trying to find a way to work, even if it means giving away a book that sold a respectable 17,000 copies when it was published in 2011. The editors and writers who create books, most based in the U.S. epicenter of the pandemic, New York, and the retailers across the country who put them into customers’ hands are not considered essential businesses. They are effectively on hiatus.

And yet this crisis should be an opportunity for book publishing, a period of high demand from readers stuck at home. Ebooks and digital audiobooks are selling better than usual, alongside the print books Amazon and a few others manage to deliver. So what does the overall picture look like for publishing at a moment when readers need the industry the most? And just as important, what might it look like on the other side of the pandemic?

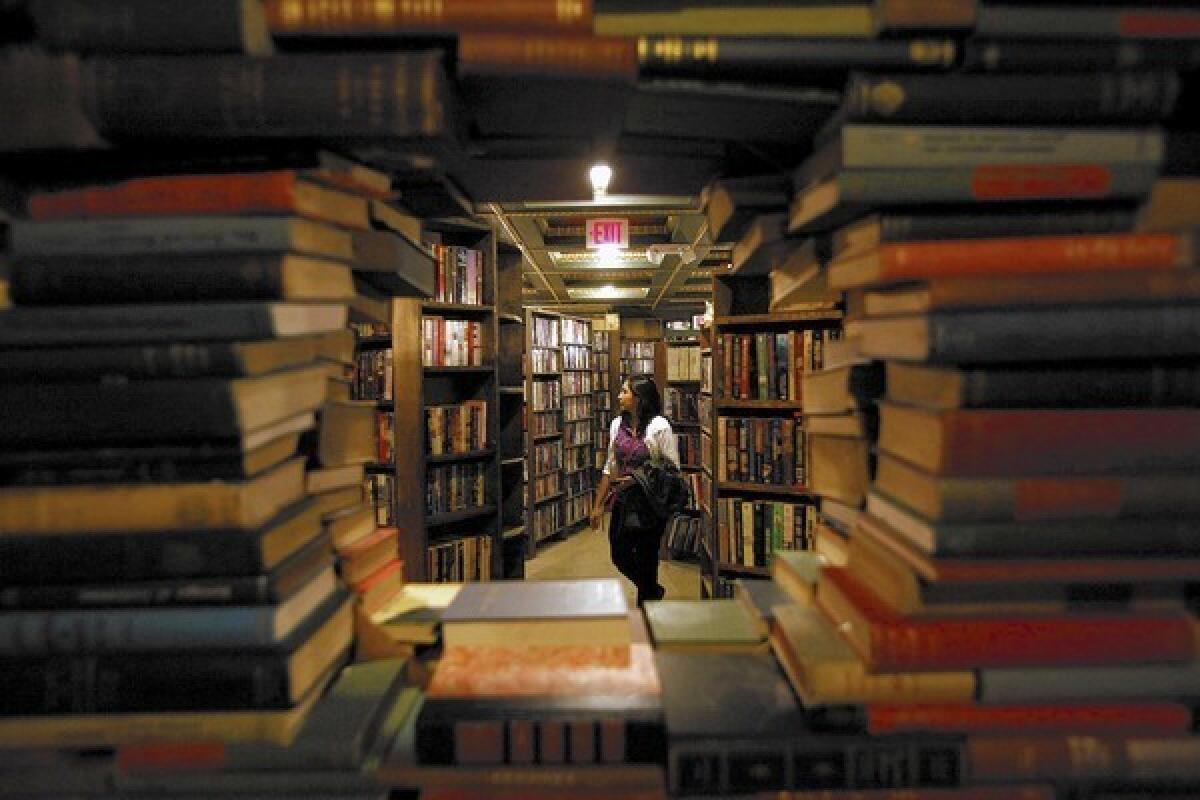

First, there is the short-term tragedy of the independent bookstores, which some segment of the population considers essential — especially store owners themselves. Nancy Bass Wyden, owner of the Strand bookstore in Manhattan, filed a request with the New York governor’s office to stay open just a day after laying off 188 booksellers. “We strongly believe that our 18 miles of books are a vital resource the world could really use right now,” she said in a statement posted online. If anyone understands the levers of government power, she does: her husband is Ronald Lee Wyden, the senior U.S. Senator from Oregon, whom she is said to have met while visiting the famous Powell’s Books in Portland, Ore. — a bookstore chain that, incidentally, laid off more than 360 of its own unionized employees last week.

Bookstores outside of shelter-in-place zones have done their best to shift to telephone or online orders (though many still don’t offer online ordering). To sell a book, they generally have two options: They can pull one from their own shelves and deliver it curbside or to the customer’s home; or if it isn’t in stock, they can have it shipped by one of the handful of national book distribution companies, which have been deemed essential and remain open but are equally vulnerable to illnesses or further lockdowns.

“If [the book distributors] shut down, it’s going to be a nightmare for us,” said Mitchell Kaplan, who runs Books & Books, which has five stores in Miami and is now online-only after letting 90 employees go.

Like most others, the industry is holding its breath and counting its meager blessings. The booksellers who have managed to keep things going by shifting to online orders and deliveries have seen a small surge in sales, but the majority report that the volume doesn’t come close to that of a typical day. There’s also widespread skepticism that customers will keep it up — fear that this is just a temporary show of collective goodwill.

Allison Hill took over as chief executive of the American Booksellers Assn., the trade group that represents some 1,880 companies, on March 1. Prior to working for the ABA, Hill was a long-time resident of Los Angeles, where she was the president and CEO of Vroman’s in Pasadena and BookSoup in West Hollywood. Now, she spends her days lobbying the government for relief and support for bookstores, many of which are now under threat of closing permanently. Despite what has for several years been touted as a resurgence of independent booksellers, only a third of indie bookstores were profitable before the coronavirus, according to the ABA, which said several were “getting killed in the retail apocalypse.” Even the most successful and beloved bookstores are desperate. Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor, Mich. — Publishers Weekly’s 2019 Bookstore of the Year — just crowdfunded $100,000 in working capital to ensure its survival.

How bad is it for bookstores, really? Just ask the Book Industry Charitable Foundation, a modest nonprofit that offers help to booksellers in need. They have raised $700,000 since the start of the crisis and anticipate a minimum of one thousand booksellers needing at least $1,000 each in the near term.

So with stores closed and thousands of booksellers unemployed, who might step up to serve increasing demand? Online retailers are reporting a surge in demand for print books. The ABA’s own online bookselling sites clocked a 250% increase in traffic; Bookshop.org, which just launched in February and partners with indies and media, reported a 400% increase in sales, which put $100,000 back into bookstores’ bank accounts.

Presumably, this surge extends to Walmart and Amazon.com, though the latter, which accounts for as much as 50% of U.S. book sales, has officially “deprioritized” delivering books and now lists many bestsellers as not shipping for several weeks. Barnes & Noble, still the nation’s biggest bookstore chain, has managed to keep its stores open wherever it can. Last week, CEO James Daunt said, “Our sales are up very strongly but we’re necessarily preparing our company and our booksellers for the potential that it could come to a standstill.” Were that to happen, mass layoffs might dwarf those of the indies.

The big question in publishing is whether this is the moment people turn to ebooks. Book lovers have never quite embraced them to the extent that was predicted when Jeff Bezos first introduced the Kindle in 2007. Sales have been in a slow, steady decline, partly due to the fast-rising popularity of downloadable audiobooks.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, ebooks are selling at “about the level we would see during the holidays,” Michael Tamblyn, CEO of ebook and audiobook seller Rakuten Kobo, told this reporter for a piece in Publishers Weekly. Libro.fm, which sells downloadable audiobooks through independent bookstores, reported “record sales” since the start of the crisis. If these smaller retailers are seeing such a big boost, major digital platforms like Apple, Google, Amazon and its subsidiary Audible surely are as well. (Big tech is cagey about releasing sales numbers.) Libraries across the U.S., also shuttered, are shifting resources away from print books and pouring money into ebooks.

Despite the shift in habits, temporary as it may be, the industry as a whole — never a fast-moving one — is now frozen. Author tours are canceled; book printings are on hold; layoffs may be coming. Publishers are pulling out of springtime industry gatherings such as New York’s BookExpo — now postponed until summer while its venue, the Javits Center, becomes a temporary hospital.

The great debate is over what to do with forthcoming books: Do you move them, like the new James Bond movie, at the risk of doing the once-unthinkable — putting out a big book in the middle of a presidential election? Or do you plow ahead, and hope the social media gods will look kindly on your efforts (provided the publishers don’t lay off their Gen Z social media marketing team under a “last-in, first-out” policy)?

Publishing’s glacial production and sales schedule, in which even a hot book takes a year or two to reach the market, means that some of the most urgent stories will not get told as quickly. And because of its complicated business model, it will be well into the latter half of this year before we know whether or not gains in ebook sales will mitigate lost print revenue.

Looking ahead, only one thing is certain: Writers now have a lot more time on their hands to write. The end of the crisis may find literary agents inundated with fresh manuscripts. The problem is that by then, there may not be enough agents — or booksellers or publishers — left in the business to absorb all the submissions.

“While the coming months will provide more writing time for a lot of people, many will see their time reduced,” said literary agent Jennifer Carlson, partner at Dunow, Carlson & Lerner Literary Agency. “Many of us will bear excruciating grief and hardship, while others of us may get away more with discomfort and upheaval.”

Still, she was looking forward to the forthcoming material: in nonfiction, “even more about our ever-deepening systemwide global and domestic sinkholes”; while in fiction, “I suspect that magical realism and genre bending could do a lot to address current reality — a ‘Calgon take me away’ setup with a firm grip on human ingenuity and undiluted rage.”

And who is likely to benefit most from all this chaos, ingenuity and undiluted rage?

The last publisher assured to be left standing, the one that has a built-in audience and will never have a shortage of customers, the one with a parent company that is actually benefiting in this dire moment, the inventor of the Kindle and unagented self-publishing: Amazon.

Nawotka is the bookselling and international editor of Publishers Weekly.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.