What if Hillary had dumped Bill? A novelist imagines a different 2016 — and beyond

- Share via

I know you want to know what happens in the second half of Curtis Sittenfeld’s “Rodham.” The premise of the much-anticipated novel by the author of “Prep” — that Hillary rejects Bill Clinton’s proposals of marriage and goes on to lead a different life than the one we’ve all picked over like a headful of lice — is titillating. Especially for a quarantined reading populace craving a rewrite of our cursed trajectory. Especially from a writer who’s already published a novel, “American Wife,” that brings an enigmatic first lady (Laura Bush) to life.

The first thing Sittenfeld and I discuss by phone one quarantined morning is how much to reveal, because too much would constitute a literary sin. Here’s what we agree upon:

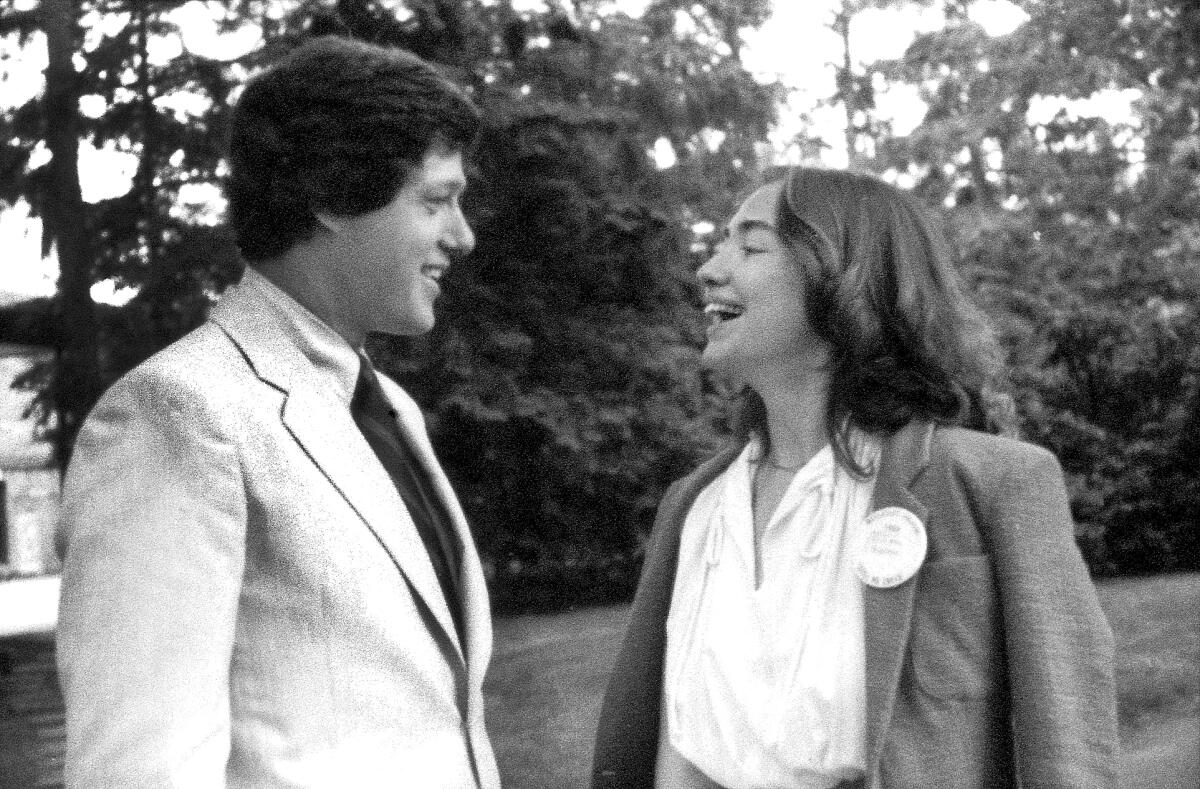

In 1970, Hillary Rodham, a Yale Law student with a penchant for earnest activism and committee leadership, catches sight of Bill Clinton, “a handsome lion … a person who took up more than his share of oxygen.” They fall in love after two dates and spend a few years in swoony (and erotic) bliss. Bill asks Hillary once, twice, to marry him, and she agrees. But there’s a snap in the relationship (you’ll probably guess why) and then a feeling in Hillary’s gut that she can’t intellectualize away. She stays a Rodham, never a Clinton.

I can tell you she considers a run for public office, that the propulsive life Sittenfeld has invented for her — in a smartly structured character study and a stay-up-all-night plot — zooms all the way to the 2016 election, with cameos from more than a few political celebrities. I can say there are dozens of Easter eggs along the way, concordances between Hillary-as-Rodham and Hillary-as-Clinton, some based on scandals so memorable they are practically erected in neon.

And yet for all the jacket copy about reimagining Hillary, Sittenfeld says she was driven by a different question. “The conversation about Hillary Clinton for 30 years has been, What does Hillary mean? What do the American people think of Hillary? And, what I wanted to ask was, What does Hillary think of the American people?”

Sittenfeld knows she’s lucky. “I have as stable a writing career as a novelist can have without being Stephen King,” she says. When she brought the idea for “Rodham” to Random House, her publisher of 17 years, they let her run with it without seeing a full draft. It helps that Sittenfeld’s work occupies the sweet spot of the Venn diagram composed of what the writer Emily Gould, Sittenfeld’s friend, calls “literary fiction and, for lack of a better term, women’s fiction.”

Yet Sittenfeld didn’t just helicopter in and land on top of the heap. She is an archetype of the fiction writer who is lucky because she hit every milestone on the way up. Like her latest subject, she knew her path to success because she’d tossed it out in front of herself, a breadcrumb trail of future accomplishments.

“Rodham” was announced in 2017, as many Americans walked around with the equivalent of a political concussion. Its publication date is coincidental, Sittenfeld says: “It was not some master plan to make it come out around the 2020 election.” She appears sensitive to the idea that she can manufacture buzz. “After the fact,” she says, “a successful or unsuccessful book seems inevitable. But I think you actually cannot game publishing.” Especially during a pandemic, it’s impossible to know whether the reading public will show up for yet another take on Hillary, a woman whom even many Democrats never want to hear from again.

“I was a senior in high school when Bill Clinton was elected,” Sittenfeld explains to me from her house in Minneapolis one April morning. “I was impressed by [Hillary], and it was endearing to me that he was married to her. He had married an opinionated, professionally successful woman.” That’s not exactly a high bar now, Sittenfeld knows, but in 1992 Hillary’s braininess and policy chops were seen as violations of the First Lady Code.

Like Hillary herself, Sittenfeld was (and is) an ambitious Midwesterner. Raised in Cincinnati in an upper-middle-class family, she trotted off to prep school at Groton School and then racked up all sorts of frameable accomplishments. She won Seventeen magazine’s fiction contest for high schoolers with a story about a young girl at prep school. When she was at Stanford, Glamour named her a College Woman of the Year. The accompanying photo showed all the other winners kicking their legs like can-can girls and Sittenfeld “in a dowdy black dress and huge plastic glasses, frowning and not kicking my legs at all.” (“The Christmas I was 17,” she once wrote, “the only present I asked for was a copy of ‘The Bell Jar.’”)

After teaching at the posh, all-boys St. Albans School in D.C.’s “upper caucasia” and some time in journalism, she sold “Prep” for the unremarkable sum of $40,000. Its success was immediate — “a surprise bestseller,” she says, it’s sold nearly a million copies in print — and entirely unexpected. Critics contained their enthusiasm, but audiences turned it into something much more than a cult classic. Its spare J. Crew catalog of a cover, with a flamingo pink and lime green grosgrain belt, was a subway status symbol.

Her next novel, “The Man of My Dreams,” hit a sophomore slump. And then she re-encountered Hillary Clinton — as research for “American Wife,” her quietly absorbing first lady roman a clef. Reading Clinton’s 2003 memoir, “Living History,” Sittenfeld saw her afresh. “There has been, for my entire adult life, reflexive cynicism toward [Hillary],” she says. The memoir “made me kind of reconsider it.”

Sittenfeld says the idea for “Rodham” didn’t occur to her until almost a decade later, just after Hillary accepted the Democratic nomination. “American Wife” had been released to acclaim, followed by “Eligible,” a “Pride and Prejudice” rewrite, and “Sisterland,” about psychic twins, which prompted the New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani to dismiss her “high-concept gimmicks.” In light of that trajectory, a return to first lady lore was, depending on how you look at it, either a doubling down or an incredible risk.

“American Wife” defends Laura Bush (in the guise of narrator Alice Lindgren), offering her up as a kind of resistance hero who secretly votes against her own husband and then admits on television that she’s against the Iraq War. In a review, Joyce Carol Oates felt that it went too easy on the Bushes and tucked away “unconscionable, even criminal behavior cloaked in the reassuring tones of the domestic.” Sittenfeld’s Hillary, in contrast, is relieved of her scandalous patriarchal burden in the early going. A critic’s reflexive instinct is to see a pattern here — Hillary as the next step on a path tentatively trod by Alice/Laura. Laura rebelled against her man; Hillary outright rejected hers.

When an editor at Esquire reached out to Sittenfeld in February 2016 to ask for a short story imagining Hillary’s state of mind at the coming summer convention, “I wasn’t even immediately certain I wanted to do it,” Sittenfeld says. She raised the question of what the magazine might do if Bernie got the nomination instead. “I wondered how the story would correspond with reality,” she says with an undertone of chagrin, “but it turned out I did not wonder in the right way.”

It was a few months later Sittenfeld had a moment of internal reckoning. “I thought, Have I ever written fiction from the point of view of a professionally successful woman? … What’s up with that?”

In Sittenfeld’s Esquire piece, “The Nominee,” Clinton sits backstage with a reporter who has doggedly tracked her career; Hillary has much the same opinion of the journalist that many Americans seem to have about her. The reporter has a “blazing, undeniable intelligence,” but there is something off-putting about her, a sense of entitlement. (This journalist, Sittenfeld offers, is based on a composite of two people, but is decidedly not Amy Chozick.) At the end of the story, Hillary imagines herself blurting out the unsayable: “You’ve mentioned many times over the years that you find me unlikable. How do you think I find you?”

That voice — exacting and plainspoken, sharp but perplexed at her inability to win hearts — carries over into the novel. “Rodham” is essentially a fictional version of a memoir Hillary might have written.

Perhaps for that reason, it takes a while to settle into. Hillary Rodham, like IRL Hillary Clinton, is not a weaver of yarns. For the first 20 pages or so, Gould worried: “She’s not going to be able to pull this off,” she thought, “I’ll never believe this as a plausible alternative history.” But Sittenfeld knows she’s surprising us, using this dry, unconventional voice to build a captivating and durable story containing rooms within rooms. “Rodham” turns into a high-speed bildungsroman about a woman of formidable intellect and self-insight. As Gould concluded, “She totally pulls it off.”

Only about two paragraphs made the transition from short story to novel. In one of them, Hillary remembers being at her friend Carol Gurski’s birthday party, age 10. Seated at the table with her piece of cake, she opines in detail about Ernie Banks and the ill-fated Chicago Cubs. Carol’s father smiles “unpleasantly” at this vivacious little girl, “in a way I had never previously recognized but have observed on a daily basis ever since.” He then offers, “You’re awfully opinionated for a girl.”

Versions of this sentiment pop up throughout Hillary’s life. An elementary school crush tells her, “You’re more like a boy than a girl.” A Harvard Divinity grad student shuts down any possibility of romance by saying: “I really enjoy discussing theology with you.” Her interactions with the opposite sex and her confusion about exactly how she might properly modulate her intellect, form a knot at the center of her identity. Hillary doesn’t want to have it all, per se; she just wants to know what she is allowed to have. “I always hoped a man would fall in love with me for my brain,” she tells her friends. She’s smart and knows it, a combination that can prove poisonous for a 20th-century woman.

It’s a typically Sittenfeldian character — the well-meaning white woman missing the social clues her more intuitive peers seem to navigate effortlessly. “She lets us see into people’s intentions, and at the same time we can see how those intentions are about to pan out,” says memoirist Mary Laura Philpott. “You read with one hand half-covering your eyes because you see the inevitable embarrassment coming.”

In “Prep,” Lee Fiora boxed herself into the role of imperious outsider; the 2018 story collection “You Think It, I’ll Say It” teemed with women who misread social cues. Such mishaps have a literary whiff of the 19th century; it’s not hard to see the classics in which teenage Sittenfeld immersed herself bubbling up in her fiction. (“Emma,” anyone?) But Sittenfeld’s women encounter decidedly modern problems, like starring in unflattering viral videos — or, in the case of Hillary Rodham, pursuing a life of professional exceptionalism. These are novels of manners set in an age of radically shifting norms. The protagonists can’t keep up — until we get to Hillary.

On the cover of “Rodham,” a young, almost life-size Hillary, in her Wellesley graduation robe, stares into the distance. It’s both an enticement and a challenge. “It’s not everyone’s dream come true to read a novel imagining Hillary hadn’t married Bill and how that might have changed 2016,” Sittenfeld says with a laugh. “If someone says, ‘I do not want to read “Rodham,”’ I think, you do not have to!”

It’s not that Sittenfeld isn’t thinking of sales, just that she’s thinking of them differently. “American Wife” played coy with its subject; its cover showed the torso of a woman in a modest silk wedding gown, her long white-gloved hands folded sedately on her lap. It was a book setting out to liberate a woman from her husband’s legacy, without quite defining her independently or even speaking her name.

“Rodham” is on a different mission. “At one point,” Sittenfeld says, “I talked to my American publisher about different titles, and one title floated was ‘Significant Others.’ Let’s say the title had been ‘Significant Others’ and then there’s a woman in a pantsuit and you see her from the side, or you see pearls …” That’s a totally different book, I posit. She agrees. For years, women’s faces have been cropped out of covers, their identities hidden behind archetypes. By putting Hillary’s name and face front and center, Sittenfeld has not only made Rodham’s ambitions plain; she’s also announced her own — to rewrite a piece of contemporary American history from an unapologetically personal perspective. “I just thought, it’s about Hillary. She’s called Hillary. Just let the book be what it is.”

I ask if Clinton has read the book; Sittenfeld says she isn’t sure. “I feel a little confused about what to do,” she says with a laugh. After all, this isn’t a gift or an offering. The novel isn’t for Hillary. She knows her own life, and she doesn’t need a do-over, fictional or otherwise. It’s readers who want that, and Sittenfeld who wants to give it to them.

Kelly’s work has been published in New York Magazine, Vogue, the New York Times Book Review and elsewhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.