Are Little Free Libraries helping locals survive COVID? L.A. weighs in

- Share via

Two weeks after we installed our Little Free Library, the first “Star Trek” novel appeared. After a week, my spouse, the family curator of our blue box of books, took the novel off the top shelf — deliberating whether to read it or recycle it. The next morning, he decided to return it and had an unexpected encounter: another “Star Trek” novel.

This one, it should be noted, was the second book in a four-part series, unrelated to the previous “Star Trek” novel.

“Who does this?” bemoaned my spouse, “Why do people give away unreadable books?”

A few days later, a third one showed up.

On some level, little libraries have always existed. The idea is simple and timeless: boxes, tables and stoops loaded up with free books. The philosophy behind them is also simple: Take a book, leave a book.

Since the 2009 establishment of Little Free Library, the official nonprofit organization that maps and sells these public bookshelves, charters have flourished. The group lists more than 100,000 registered libraries in 108 countries.

The nonprofit is doing its best to weather the pandemic. While revenues have been “a bit down,” according to an email from executive director Greig Metzger, direct sales are up around 8%. “More people and organizations are joining in.”

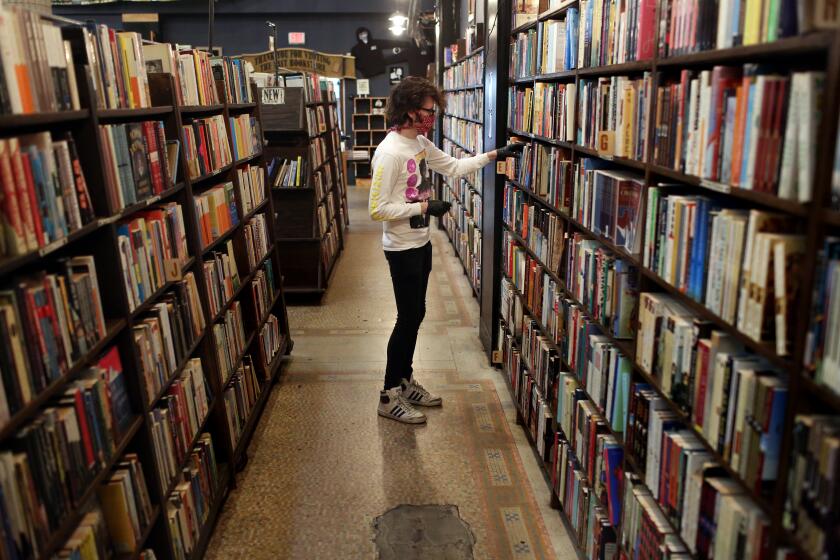

Like their peers across the U.S., booksellers in L.A. are adjusting to partially reopening their stores for curbside pickup amid the coronavirus.

Little Free Library started up during the Great Recession, at a time when massive unemployment threatened many communities’ access to books. It seems just as important today, as the pandemic has forced people to buy and borrow as locally as possible.

Poet and Bell Gardens native Vickie Vértiz has seen the little structures, often shaped like schoolhouses, throughout various neighborhoods in Los Angeles. She remembers the camaraderie fostered by sharing books with her neighbors as a child. With plenty of people under quarantine, Vértiz said by phone, small interactions at a book exchange can be crucial.

“Little Free Libraries are now emerging as cool places where community can still exist,” said Vértiz.

Sarah Rafael García, director of the LibroMobile project and bookstore in Santa Ana, believes free books can help mitigate the area’s gentrification. Her little library is an homage to places like Librería Martínez, “a landmark in my hometown, the first bookstore that focused on Latino/Latina literature that I encountered.”

When Librería Martínez closed in 2016, García put together a grant for LibroMobile. Four years later, it has grown into a small installation in an alleyway that boasts its own Little Free Library, made of a painted board and three bolted crates.

“One of our goals is always to make relevant literature accessible, so we’ve always had a Little Free Library part to our bookstore,” said García by phone. “Even though we don’t sell books over $20, you can still walk away with something.”

And yet, all across town, free books have lately gotten harder to come by — never mind good ones.

“One of the boxes we usually visit is shut down — like they taped it up … they didn’t want to be spreading germs,” said actor and Eagle Rock resident Jay Duplass. “I have not seen people frequenting them, and we’ve not frequented [any libraries] since this all started. … We love Little Free Libraries, but this was in pre-COVID-19 times.”

No one touches anything they don’t have to these days, and books are no exception. Even with reduced hours and staff, customer quotas and other safety precautions, bookstores remain mostly empty, with the bulk of sales happening online.

As California bookstores gradually being to reopen during the coronavirus pandemic, here’s a closer look at the state of the industry.

Libraries also have had to contend with upheaval. The Los Angeles Public Library offers “Library to Go” services at some locations, but this requires requesting a book and then navigating an overstressed system.

Anthropologist Hanna Garth, who lives on the border of Los Feliz and Silver Lake, weighed her options and decided that a Little Free Library was the best choice.

“It would be worth the small risk of getting COVID if I could find a great book,” Garth wrote in an email. “I rationalized it as less exposure than actually going to a bookstore.” Moreover, “I washed my hands as soon as I got home, as I always do after walks. I left [the book] in the closet to quarantine it for 24 hours.”

Unfortunately, it wasn’t worth it. The book “was quite terrible — ableist, homophobic, racist and just plain boring. I thought that was some sort of karmic response of the universe telling me not to take books out of free [libraries] during a pandemic.”

Of course, any free book carries the risk of disappointment — but the risk of disease only magnifies it.

“I find the little libraries incredibly annoying,” said Highland Park writer Myriam Gurba by phone. “They’re often eyesores — just not attractive. They’re supposedly-cute trash receptacles full of books that should have never been published. I don’t want to touch them, especially now but maybe not ever.”

Inside a packed room in Culver City on Thursday, Myriam Gurba, Roxane Gay and other writers of color talked about “American Dirt,” Macmillan and the “crisis” in U.S. publishing.

As Emory University librarian Karen Garrabrant pointed out by phone, “People often use Little Free Libraries to clean out their old books, because we have a subconscious inability to throw them away.”

When I explained my “Star Trek” novel problem, Garrabrant laughed.

“That makes perfect sense,” she said. “Sci-fi/fantasy readers read more than anyone I know. The people who are most generous with Little Free Libraries are sci-fi people. They just always have a book on them.”

Duplass, for all his love of the libraries, can’t help agreeing. “Sometimes they put the worst books in there,” he said. “One of the libraries I visit, that will go unnamed, is a place where books go to die.”

It’s a vicious cycle but can also be a virtuous one, says the actor. “If you rely on this one library, and they give you good books, you are more likely to take your good books and deposit them there. It creates its own goodwill cycle. [But] we would never take a nice book of ours and put it in that trash-depository bookshelf. … We can’t support that situation, you know?”

For Gurba, the stakes are higher than just a bad book: “We’re not discussing whether or not the owners of these libraries are good curators.” In other words, COVID or not, a cute curbside bookhouse is no educational substitute for a robust library system.

“The best libraries are the carefully curated ones,” says Garrabrant. “Community engagement creates more engagement, which leads to better books. Now, it’d be interesting if public libraries got involved.” Perhaps, she adds, “We could rethink the work of a librarian now that people can’t go into libraries.”

As Garrabrant points out, physical libraries don’t always have the best books either. “That’s the point of browsing: to find the gem.”

The Little Free Library has evolved during the pandemic to take on new functions. Many now offer hand sanitizer, toilet paper and other necessary items. Some have even removed books completely to become neighborhood pantries. But books always have a way of coming back.

Inglewood resident Maygan Orr runs a “blessing box,” containing nonperishable foods and pandemic supplies. Recently, the contents of the box have been changing.

“I’ve noticed that people have not only been donating food,” Orr wrote in an email, “but also DVDs, books and informational materials from the Inglewood Public Library. We’re keeping people well-fed and well-read!”

Over the last three months, 17 writers provided diaries to the Times of their days in isolation, followed by weeks of protest. This is their story.

For some, the quality of the books feels irrelevant. “Those boxes can be vital in low-income neighborhoods with lots of kids,” said Vértiz. “Every neighborhood should have one, but … maybe that’s an issue. I don’t really see Little Free Libraries here in [Bell Gardens].”

Metzger, the Little Free Library executive, says the situation is improving. “Historically, the distribution skewed toward suburban neighborhoods. And while that is still the case in percentage terms, through our Impact Library program we are providing more book exchanges to under-resourced communities, be they urban, suburban or rural, in absolute numbers.”

It’s the urban and rural locations that need them the most. Little Free Library offers some starter books on its website, mostly geared toward children. Childhood literacy and access was the organization’s founding mission after all.

As its website notes, “Children growing up in homes without books are on average three years behind.” What will that mean during a pandemic, when access to books is even more scarce?

My neighbor finally admitted to putting the “Star Trek” novels in our library. They were duplicates, she explained, and perhaps someone was missing exactly this book in the series. After I decided the books should stay, my spouse made a rule: If no one grabs them in a couple of months, we’re recycling them.

Whatever comes of the “Star Trek” books, the pleasure of browsing remains: scanning a shelf, laughing at the disappointments and reaching over — even during a pandemic, even when the world is on fire and the library shuttered — to pull out a good read.

As long as you quarantine it first.

Quarantined in Riverside, novelist Susan Straight watches “Gunsmoke” and “Gentefied” and gives away Judy Blume and National Geographic.

Ramírez is a poet and the author of “Dead Boys.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.