Review: Los Angeles under a theorist’s microscope, only sometimes in sharp focus

- Share via

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There’s a wall of books about L.A. that are much worse than “City at the Edge of Forever” by Peter Lunenfeld. But my guess is this UCLA professor’s first non-academic title might serve as better source material for a subsequent, more urgent project — one that focuses less on theory and more on making us care. An often intellectually rigorous exploration — with explosive bits of insight and erudition, sections that feel like promises for what could have been — this wide-ranging collection of essays is alas too-often clunky and haphazard, reading like notes toward a more complete and engaging book.

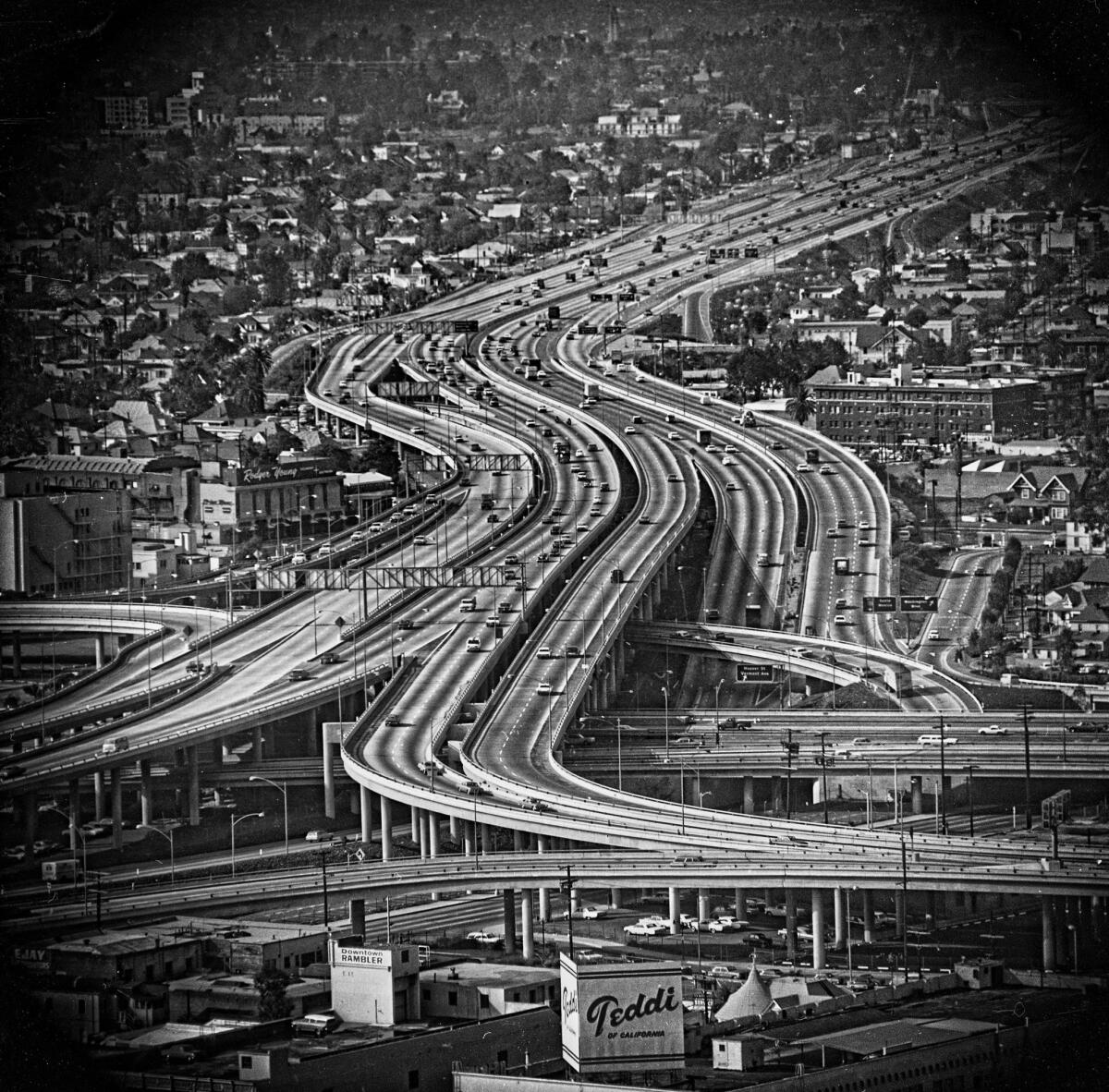

Not a small thing: The chapter headings include gorgeous photos of highway overpasses foregrounded by juicy and surprising quotes from Angeleno (or at least L.A.-adjacent) icons as various as Raymond Chandler, Robert Heinlein, Ray Eames, Roy Choi and Bruce Lee. The chapter titles and subheads are a delightful mouthful. (Example: “Freud, Dora (No, Not That Dora), and the Secret Austro-Hungarian Roots of Surfing.”). Yes, please.

But, surprise! Lunenfeld’s an ex-New Yorker, which is not necessarily fatal but does spawn some clunkers. “[P]eople on the West Coast wear their learning more lightly than I was used to,” he writes wistfully, but then signals his evolution: “I learned that the place I’d moved to, hoping it would have so little history that I make have a chance to make some myself, instead rewarded constant digging and curiosity.” And yet still, now that he’s lived here 30 years, a lingering Gotham-centric posture can result in lines like this: “But people with brains (often from New York) kept streaming west regardless,” a level of implicit condescension that should sound familiar to anyone with a New York Times subscription.

A New York Times reporter who covers online culture is relocating to Los Angeles, and she needs your advice.

To use some of the book’s cultural vernacular: When it’s really good, it’s like a Dead Kennedys song, which is to say sharp, fast, surprising, confrontational, a bit profound. When the book is bad, it’s like an entire Dead Kennedys album: fast, dutiful, unsurprising, flat and a bit silly.

The Vice Chair of UCLA’s Design Media Arts department, Lunenfeld is at his best in chapters like “Gidget on the Couch,” lingering at the intersection of art and the way we actually live: “Just as surfing is a sport that most people experience through photography — there are lots of readers of Surfer and Surfline.com in Indiana and Arkansas — so, too, is high-modern architecture something that most people experience only through images.” He continues, “It can even be said that surfing and modern architecture are designed for the perfect moment of photography: in surfing that instant in the tube before the wave closes in, in architecture that brief interval between the end of construction and the day the clients move in their possessions.”

Leaning into his expertise, Lunenfeld is equally adept at narrating changes in the way we’ve made our homes. “The floor plans of middle-class homes expanded,” he writes of the 1950s, “so that the sounds and smells of sex were cordoned off from the rest of the household …The children born in the second half of the twentieth century were truly modern. ‘Things’ didn’t happen to them; they and the adults around them made ‘things’ happen for them.” Further riffs on Disney and Playboy come in his chapter “The Factory Model of Desire,” resulting in this kind of serious fun: “In Southern California, when asked what they did for a living, Walt’s people would say, ‘I work for the mouse,’ while Hef’s responded, ‘I work for the bunny.’”

Likewise, Lunenfeld’s on fire when he speculates on the consequences of Southern California’s many secret aviation projects, concluding that “homes, communities, and whole regions that require secrecy simultaneously demand hypocrisy.” You can feel the author lighting up in these moments, delighting us and himself. Chapters that sing include micro-histories (of Bruce Lee or Ray and Charles Eames or the Sunset Strip riots) are so richly textured and engaging that they almost feel like comic books, or an episode of the “X-Files.”

Waldie, whose paean to his native Lakewood, “Holy Land,” was a 1990s classic of Los Angeles writing, pulls it off again, though a little more darkly.

But at many other junctures, you sense his heart just isn’t in this; the micro-histories can feel like gasping, run-on summaries. The killer gives way to filler, as in the aviation essay: “By the 1930s, the economy took to the skies”; “air’s ascendancy was linked to conflict, and even on the home front it was hardly an era of harmonious relationships.”

It’s not impossible, of course, to be an academic and write well for a larger audience. Maybe more of the author’s skin in the game would’ve helped? Or a more brutal pruning of his many cliches (War machine money? “[L]ike a rain of gold.” The original Gidget? She’s “ninety-five pounds when wet.” Freud was “that famous son of Vienna,” and so on.) In the acknowledgments he describes walking on the beach with the surfing story’s actual inspiration, Kathy Kohner-Zuckerman. Why not make that a scene?

At times, the accumulation of references (Scheherazade, Timothy Leary) and half-cool patter makes you feel like you’re stuck in an elevator, on acid, with a possibly dosed professor trying too hard and not knowing when to stop. Whoa, Dennis Hopper worked with a witch who’d had sex with a dead man? Please stand clear of the doors ... of perception!

A finer vein of discomfort and attraction: some of Lunenfeld’s politics feel distilled from a mid-1990s copy of Adbusters. Which is great. Who doesn’t want razor-sharp skepticism of capitalism and its attendant power structures? But that posture can grate against the problems of today — as when he writes that Disney “could stand to be a bit more woke.” Or when Lunenfeld theorizes about “Wife Swap” and “Supernanny” or — just chuckling to himself or with us? — when he muses that the producers at HGTV, in renovating the original Brady Bunch House, should have read some Baudrillard. OK.

It’s an old saw, the idea that you can come here to reinvent yourself, but Lunenfeld does a decent job of giving it a new metaphor, calling his hometown an “ever-refreshing Etch A Sketch, a tabula rasa that could never be filled, free[ing] generations to explore their own possibilities[.]” Later, he points out succinctly that what we get by living here is “space, light, and opportunity, the classic California trio.”

“Discovering Griffith Park,” a history-rich guidebook by Casey Schreiner, gives one of the country’s largest, greatest city parks its due.

So what’s this book actually about? A sort-of cultural history, a semi-treatise on design, a bit of music criticism — but certainly a modest addition to the L.A. canon. In that spirit, we can all enjoy Lunenfeld’s brio when he reports that an optional carbon fiber cup holder on a new Ferrari costs $3,533.

Deuel is the author of “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.”

City at the Edge of Forever

Peter Lunenfeld

Viking: 336 pages, $28

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.