Review: How Reagan and the finance bros gave us Trump

- Share via

On the Shelf

On the Reagan Legacy

Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America

By Kurt Andersen

Random House: 464 pages, $30

Reaganland: America’s Right Turn 1976-1980

By Rick Perlstein

Simon & Schuster: 1,120 pages, $40

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

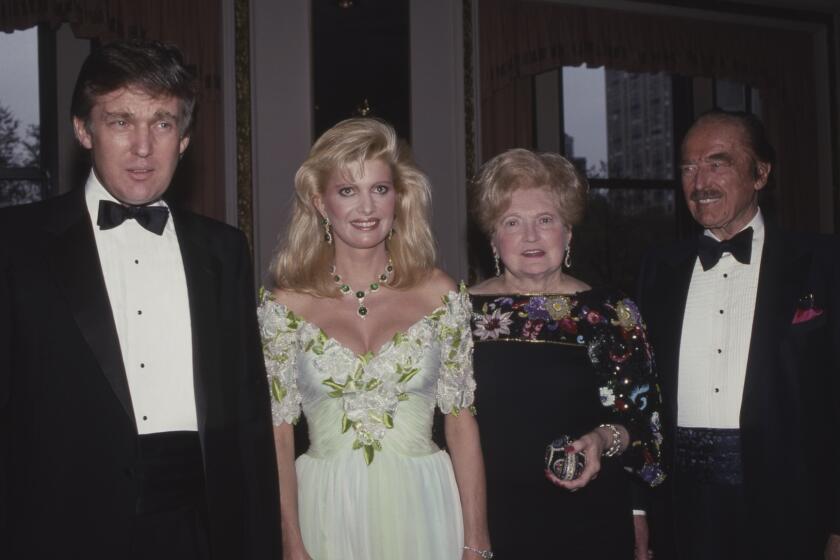

The 1980s brought with them a new social type, a sub-Nietzschean popinjay we’ll call Finance Guy. A bantam alpha, gut sucked into his chest, shoulders padded out like a linebacker, hair center-parted and pomaded back; the little creep who makes nothing but takes a fee on it anyway. The Reagan revolution had handed power — real power, the power to shape our collective fate — back to the bankers, who’d been laid low since 1929; and this, in turn, unleashed an epidemic of ridiculous self-importance for which Spy magazine was the perfect antidote.

A lampoon founded in 1986, Spy immediately took its place within ’80s New York, a city giving itself over to the rackety energies of the vulgar and profane. (Along with Finance Guy, Spy’s favorite target was Donald Trump, whom it famously labeled a “short-fingered vulgarian.”) The magazine’s tone — part awe, part gleeful scorn, all postmodern cheek — was later mimicked by the New York Observer, passed off to Gawker and “The Daily Show,” and is now a default setting on Twitter. There is an intelligent way to honor this legacy while being made uneasy by it. Wherever power is corrupt, satire thrives, and humor has been a necessary coping mechanism in neoliberal America; but it also helped those who know better reap the benefits of a world gone stupid without entirely losing their dignity.

I say this admiringly: No one has been better at this balancing act than Spy cofounder Kurt Andersen. Since leaving Spy, Andersen has been editor of New York magazine, a journalist, a novelist, as well as the companionable host of the Public Radio International show “Studio 360.” Now he has written “Evil Geniuses,” a book about the era in which he and Trump made their respective names. As Andersen says, his “voluminous” research led him to conclude “one important big thing: what happened around 1980 and afterward was larger and uglier and more multifaceted than I’d known.” The wreckage here is elaborate. It includes inequality, climate tragedy, oligopoly, endemic corruption and universal precarity among everyone but the ultra-rich.

Perhaps no other medium has better helped us process 2020. Our fall books special brings you the books and authors who’ve helped make sense of it.

Andersen begins his story with a potted history of the country. Appealing to our allegedly better natures, he says we Americans are creatures of the future, a forward-looking people that has betrayed its own can-do optimism. The bulk of the book, though, is a greatest-hits summary of the plutocratic takeover of America. The Powell memo, the Laffer Curve, pseudoscholarly think tanks — much of this will be familiar to readers of “Dark Money” and related titles, but Andersen is a confident synthesizer and writes with the zeal of the recently converted. His most original insight is the linking of Milton Friedman, first among free market evangelists, to the spirit of the ’60s counterculture. “Both sides,” he says, “could find common ground concerning ultra-individualism and mistrust of government.”

The author, he confesses, used to be a New Democrat, unencumbered by ideology and not “viscerally, actively skeptical of business or Wall Street either.” Once a “complacent neoliberal,” now Andersen is an “appalled social democrat.”

The President’s “only niece,” clinical psychologist Mary Trump, portrays a man warped by his family in “Too Much and Never Enough.”

What lies behind the conversion? The story he offers, of an encounter with two airline pilots, rings a little hollow. These were “successful all-American middle-class professionals who’d worked hard and played by the rules” but felt they were being disrespected in bankruptcy negotiations while their CEO walked off with a big pay raise. Should it take a random chat with an “all-American” (meaning white) guy’s guy in a bomber jacket to awaken your conscience? He indicates this “slow-road-to-Damascus moment” was a recent occurrence. And yet his own thesis is that for 40 years the country has been going to seed. What gives?

“It didn’t feel quite like a paradigm shift,” he says, trying out an alibi, “because it was mainly carried out by of a thousand wonky adjustments to government rules and laws, and obscure financial inventions, and big companies one by one changing how they operated and getting away with it.”

Nope. I was a kid when Reagan was elected and, knowing nothing about the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act, I knew enough to hate the man as a red-baiting snitch and a racist phony. The junk bond salesmen, meanwhile, told us to our faces they were rigging the game. Not only had the paradigm obviously shifted by, say, 1984, when Reagan declared it Morning in America and Madonna hymned the material world, but Andersen himself — first as a reporter at Time, then at Spy — cut his teeth covering it.

He says he knew something was amiss when he noticed the passing decades were no longer taking on distinctive styles. “The 1990s looked and sounded extremely different than the 1970s, but by comparison, the 2010s were almost indistinguishable from the 1990s, as 2020 is almost indistinguishable from 2000.” This may be true, but it is of a piece with the book’s exasperating confusions of scale. I often found myself wondering: Are we talking about an epochal shift or a random shudder in the zeitgeist? A journalist at heart, Andersen has been trained to believe in the decade as the “the standard unit of historical time,” as the social critic Christopher Lasch once put it. The shift we are undergoing now lies so much deeper than that.

Albert Camus’ “The Plague,” read in quarantine for the first time, warns us to reset our own priorities

When credit markets failed in 2008, Finance Guy was revealed as something more than an amusing cheat. He was, in fact, a liar of Orwellian proportions. He was happy to take a trillion-dollar handout from a government he’d demonized for 30 years; he’d been rigging prices while talking up the “free” market as an infallible, algorithmic god. What happened next was even more astounding: He lost all his authority but none of his power. For sinking the global economy, he wasn’t fired, much less sent to jail; and though no one believed his fairy tales anymore, the U.S. economy was converted, via a share-buyback spree, into as pure a vehicle for mindless self-enrichment as ever existed. His tax-cheating avatar is now president. This is a recipe for social rage of a kind that turns a wry, go-along, get-along no-politics politics into an offensive nonstarter.

Andersen is a gifted simplifier, and he is undeniably correct; the right has been well-funded and monomaniacal in the goal of rolling back social democracy, even in its pitifully attenuated American form. But the pitchfork and guillotine suit him poorly. As he rolled through his roster of usual suspects — Justice Powell, Arthur Laffer, trickle down, think tanks — it began to sing-song in my head like the old Billy Joel song. “We didn’t start the fire,” Andersen is saying, by way of offloading a collective guilt onto a handful of devious super villains. In “Evil Geniuses,” Andersen has served up a big helping of culpa, hold the mea. Who can blame him? He is trying to hustle one last zeitgeist. And what is the zeitgeist saying in return? OK, boomer.

**

When Donald Trump emerged as a national figure in the 80s, he was understood to be something more than a pitchman for his real estate interests. Here was an overdrawn cartoon whose purpose was driving home the new logic of hyper-competition to the masses. It’s not just that Trump was foolish, solipsistic, and physically and morally ugly. It’s that you couldn’t imagine him alone. (What he must have suffered through at Walter Reed.) Only the presence of a subordinated Other brings Trump out of his nonexistence. Hence the peculiar emphasis on the deal instead of, say, buildings. What Trump makes is suckers, and whatever else spills out of that perpetually open mouth, the subtext is always the same: Losing makes you contemptible.

Rick Perlstein’s “Reaganland” offers a majestic backstory to this meanness, in both that word’s senses: the pettiness and the cruelness of Trump’s petty cruelty. The book takes us meticulously through the latter half of the 1970s, when liberalism tottered and the country verged on nervous collapse and when the New Right, capitalizing on both trends, achieved its ultimate triumph with the election of Ronald Reagan. This is the final installment in Perlstein’s multivolume history of the New Right, told as a kind of “To the Finland Station” in reverse. Beginning with “Before the Storm,“ he has traced the virus of injustice as it worked its way from the fringes into the political mainstream, from Goldwater’s landslide defeat up to Reagan striding confidently into the Oval Office.

Perlstein’s books are uninhibitedly large items, constructed, apparently, on the principle of maximum inclusion. He is not a creature of the archives either: These are heavily anecdotal narratives, combining a rehashing of big, media-driven spectacles with a deft appreciation for the smaller tremors. The John Wayne Gacy murders, the Jonestown massacre, gas lines, gas riots, disco riots, “Star Wars,” “Rocky” — Perlstein sees American culture holistically, and his method is to implant you into the whole of a living tissue. “Reaganland” is so mammoth in scope and so scrupulously agnostic in presentation, each reader will likely find their own book in there. I walked away grateful for its larger arc.

The last major health crisis to face a president took place in March 1981 -- the shooting of Ronald Reagan. He won a bond with the public. Trump may not.

Reagan may have been a lightweight, a Hollywood hanger-on, an empty “yes, boss” corporate pitchman, but the country, by 1980, was ready for him. The Cold War establishment had lied and blundered its way through Vietnam, had strained the federal budget with the war and the Great Society and, perhaps most critically, had lost control of the currency. Carter only compounded it all by admitting, “We cannot afford to live beyond our means.” At the time, it was strictly true. But facts are no antidote to being a man out of time.

Most of us can recite a version of the Carter-Reagan bedtime story by heart. The two candidates were locked in a battle to define a single word: future. Carter felt that since our future was one of inevitable scarcity, Americans would need a wartime level of sobriety to brave it. Reagan, meanwhile — a member of the Greatest Generation who skipped out on World War II — refused to concede anything to the ideal of heroic sacrifice. “An American,” Reagan said, “lives in anticipation of the future, because he knows it will be a great place.” As Carter delivered a four-year eulogy to abundance, Reagan mastered a dream language of national innocence and middle-class entitlement. Reagan won the battle, and consequently we live in the ruins of a panacea — in a huckster’s dream, come predictably untrue.

Yes, but. Reliving this period via Perlstein in what feels like real-time detail, one is shocked to discover how much of our politics remains shaped not by Reagan, but by Carter. Carter posed a specific and very strategic challenge to the right. He was evangelical, white, Southern, racially liberal and a centrist. In response, the right consciously manufactured a new political identity out of Southernerness, evangelical Protestantism, racial intolerance and hardcore conservatism. This coalition was purely, cynically instrumental. The New Right may have had money and a vision, but as one columnist noted at the time, “The only thing it doesn’t have a lot of, it seems, is votes.” Reaganism unleashed a feedback loop: As more and more Americans get left behind economically, the right can only sustain its political success by doubling, tripling, quadrupling down on the fused identity — i.e., by fomenting a culture war.

A new documentary, “Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President,” examines the former POTUS’ relationships with icons such as Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan and Gregg Allman.

What’s most unsettling about the ’80s is only hinted at in “Reaganland”: Malaise was cured in the end by mania. That decade, ugly as it was, returned a degree of social cohesion to American life. Watching Trump “debate,” I thought for the nth time: What is holding up this sack of wind? Mysterious as that scaffolding is, we built it together — a top-down, bottom-up, fringes-in, middle-out effort. The only conspiracy here involves acquiescence. Why not own up to it? Democracy dies in broad daylight.

Metcalf is co-host of Slate’s “Culture Gabfest” podcast and is writing a book about the 1980s.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.