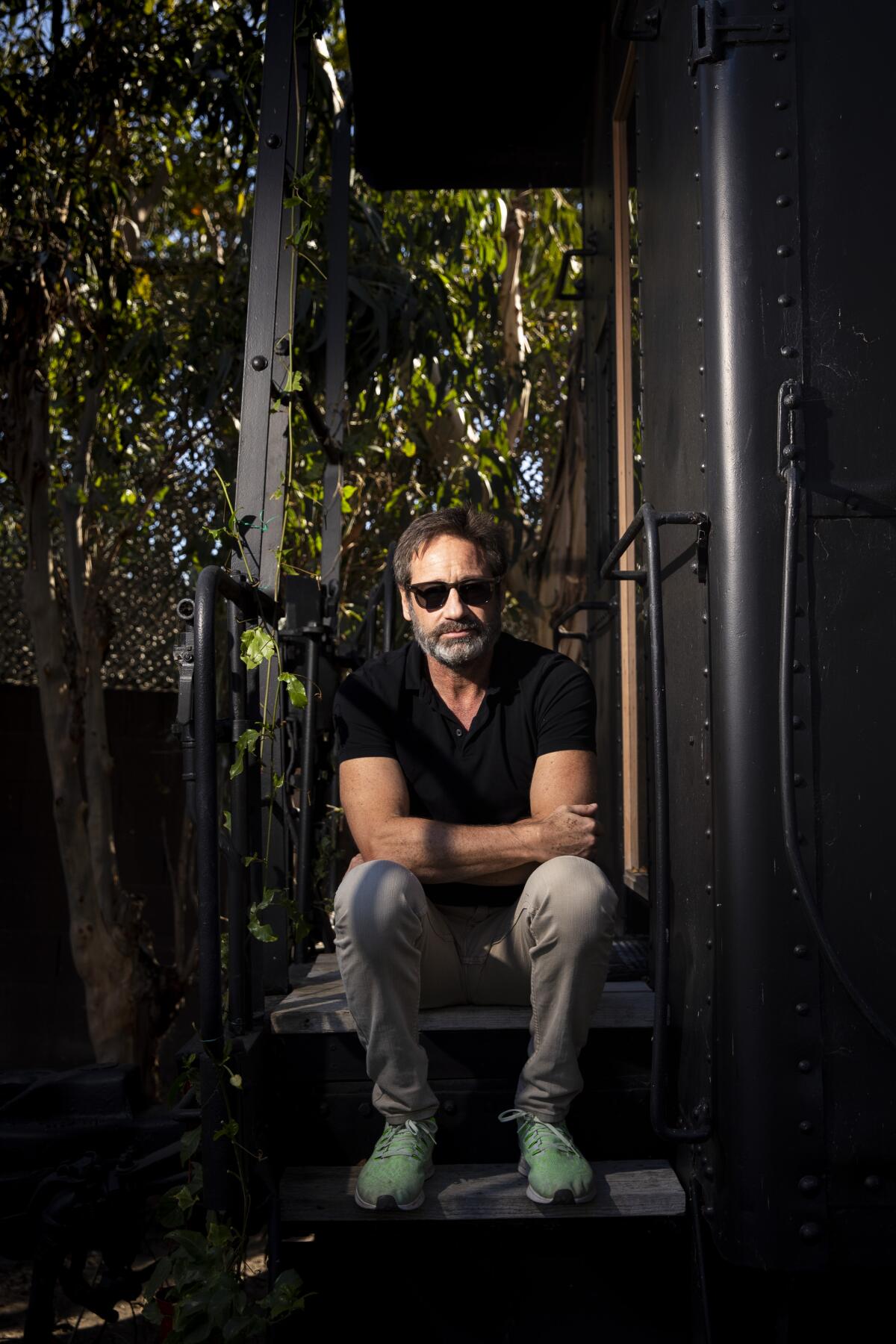

David Duchovny has more passions than his new protagonist has wives

- Share via

“Every review of a book written by an actor asks why an actor would write a book. I resent it.”

David Duchovny wants you to know he has thoughts. Big ones. And opinions and feelings. As mentioned, he uses multiple art forms to express them. Duchovny is best known for his role as FBI agent Fox Mulder on “The X-Files.” He also played Hank Moody in “Californication,” for which he won his second Golden Globe (the first was for “The X-Files”). He has also acted in dozens of other TV shows, movies and plays; released three rock albums; and just published his fourth novel.

“Truly Like Lightning” is the sprawling tale of former Hollywood stuntman and converted Mormon Bronson Power, who ditches the grid with his three wives and 10 children for a homestead in Joshua Tree. When an LSD-fueled real-estate developer on a motorcycle literally crashes Bronson’s scene, she introduces financial, social, and ethical challenges to their painstakingly constructed Eden. The story and the issues it raises feel timely and relevant, but the biggest news might be that Duchovny is good at this.

The proud multihyphenate’s polymathy was evident and nourished from childhood. Born in New York, his father a Jewish writer-publicist and his mother a teacher from Scotland, he earned a fine pedigree — sniffy, private Collegiate, summa cum laude at Princeton, a dissertation short of a Ph.D. from Yale.

“Truly Like Lightning” is about leaving all that behind — not just the trappings of meritocracy but also the worries of the Trump era. It’s a diverting read even now that Duchovny’s pre-election anti-Trump song, “Layin’ on the Tracks,” feels a bit less urgent. Duchovny spoke with The Times about the joys of writing, the power of empathy and the limitations of “political correctness.”

Out with the essay collection ‘No One Asked For This,’ David talks candidly about nepotism, Pete Davidson and a terrifying, hilarious web of neuroses.

I read that in 2017, you put your acting career on hold to focus on writing and making music. Is that true?

Not really. That’s the kind of bull— people say when they’re not getting the work they want. I tried to develop three different shows during that span. They didn’t get made. I didn’t want to be an actor for hire, but if they’d sent me an amazing script, I would have gone back to acting. Which I’m hoping to do soon. Showtime optioned “Truly Like Lightning” for an original series. Who knows if it’ll actually get on the air, but if it does, I’ll get to tell Bronson’s story in another medium that moves people in a different way.

By writing the screenplay?

No. By playing Bronson. Writing my own novel as 12 episodes would be like pulling scabs.

Strong language about something a lot of novelists dream of doing.

My inspiration to write Bronson’s story has come and gone. When I wrote it, the inspiration was pure and new. I like the guys who are going to adapt my book. They’ll make it their own. The book is the book. The show is the show. I like collaboration. That’s why you find me in the places you find me. Acting, directing, music, everything except writing — they’re all collaborative.

You obviously drew from your acting life for Bronson’s character. Why’d you make him a Mormon?

The idea for the novel came from Harold Bloom calling [Mormon Church founder] Joseph Smith “an American genius.” If Bloom says you’re a genius, that’s enough for me. So I started studying Mormonism. Which I found fascinating. Then I thought, “Uh-oh, now I have to go to Utah for a year?” Please don’t hate me. I have nothing against Utah. The problem is, I’m lazy as [crap]. I didn’t want to get off my ass. But I had to really know the area I was writing about. So I started researching, by which I mean I hired a researcher, and asked her to find out where there are Mormons besides Utah. Turns out San Bernardino, which is like two hours from L.A., was settled by Mormons. That’s where Joshua Tree is. I love Joshua Tree.

You wrote of Bronson’s escape, “He would raise a family free of the wounds an unjust society of men had inflicted upon his father and that his father had inflicted upon him.” What do you see as the “wounds of an unjust society of men”?

They call it the toxic patriarchy. There’s a lot of poison in that father-to-son stuff. As a dad, I tried to shield my kids from as much of that as I could, but so much is unconscious. You just get it. I’d find myself at my son’s baseball games when he was 10, getting furious because they weren’t winning. My dad didn’t do that. I don’t know where that was coming from. But there it was.

‘The Meaning of Mariah Carey,’ the pop star’s tell-some memoir, sparkles and entertains and explains its subject, despite a few too many I-don’t-know-hers.

How is publishing a novel different from putting out a show?

Just before you called, I got my first copy of my book in the mail. It’s a beautiful object, and I’m proud of it. Not because “I did it.” More like, I trusted myself enough to let the story announce itself to me. To allow that magic to happen. It feels like being a magician for a minute, being relaxed enough to take your hands off the wheel. All I did was open myself up. That’s not nothing. It’s hard to do. I try for the same thing with acting and music.

Which medium makes you happiest?

All of them, and none of them. I’m a depressive person. I deal with it by doing stuff. As they say, your mind is a bad neighborhood. I figured out way before the pandemic that the best thing for me is to get out of my own head and get to work. Luckily, my work is interesting to me. I do best when I feel like I’m helping other people, maybe even entertaining people. “Californication” was really good for me that way. It was playful, and I hope it helped move our puritanical society toward a less judgmental sexuality. Some people looked at it askance. They said, “Sex can be hurtful, it’s a serious subject, why are you joking about it?” Well, sex is also ridiculous, so it makes a great basis for a comedy.

The novel makes your targets crystal clear — Trump, climate denial, real-estate developers. Are you worried about alienating more conservative fans?

As a writer, I’ve actually felt more pressure from the left than I have from the right. All discourse is political now. I’m scared to write the wrong thing, to be labeled politically incorrect. That’s death to a writer. I don’t want my words taken away from me. I don’t want words put in my mouth. I feel it when I sit down to write. I’m asking myself, “Is it going to be worth it?” You can’t legislate through art. That’s called propaganda. As angry as I am at Trump, I’m also angry at feeling I can’t think out loud. A novelist has to be able to make mistakes. That’s where the good stuff is going to be.

Are you saying writers shouldn’t consider how their language might hurt people?

I understand the impulse to keep a person from writing outside their identity or experience, because that’s been part of the history of pain and injustice. I’m not saying language can’t cause problems. I’m saying the cure is empathy, putting yourself in other people’s shoes. We’re all asking other people to understand us. The desire to understand and be understood is a beautiful thing. A healing thing. That’s what writing is about: trying to create a common language that builds a bridge. That’s why I like art.

By your standards, is this novel a success?

To me, the greatest success was sitting there receiving what came to me. I’d love it if people bought the book and liked it, and if it turned into a TV show that people watched and liked because I did a good, authentic job as an actor. Actors all want to be authentic, to have feelings happen organically on film or onstage. That’s not always possible, but sometimes if you fake it, you actually start to feel it. One reason I like writing is that I don’t have to fake anything. And I definitely didn’t have to fake feeling happy when I lifted my book out of the box today.

Jim Carrey’s new semi-true novel, “Memoirs and Misinformation,” is unlike any show biz chronicle you’ve read.

Maran is the author of a dozen books, including “The New Old Me” and “Why We Write.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.