‘More pleasure, more sex, more fun’: An L.A. writer draws lessons from ancient Greece

- Share via

On the Shelf

Rude Talk in Athens: Ancient Rivals, the Birth of Comedy, and a Writer's Journey Through Greece

By Mark Haskell Smith

Unnamed: 208 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

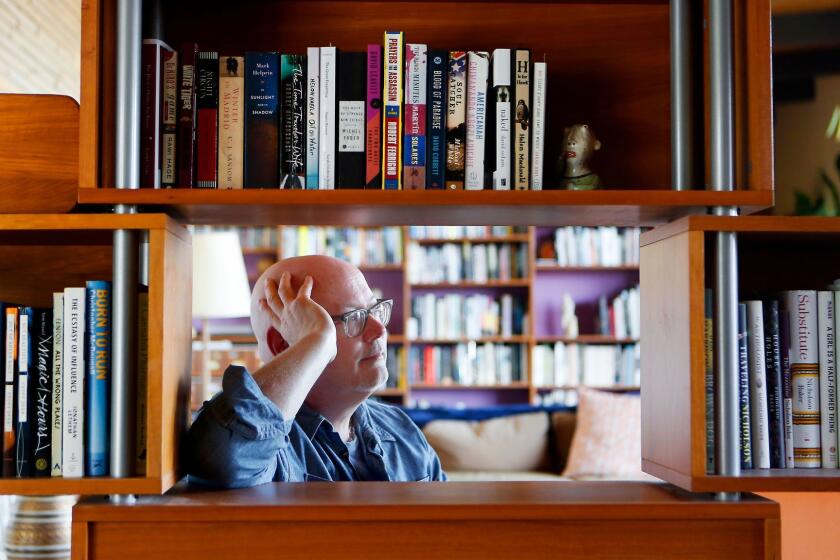

L.A.-based novelist Mark Haskell Smith has written two books of nonfiction — “Heart of Dankness,” about cannabis farmers, and “Naked at Lunch,” about nudists. His latest is in one sense a departure, a historical work about an ancient Greek playwright. But this being Mark Haskell Smith, his subject is a little offbeat: Ariphrades was best remembered not for his writings but, according to a British historian, for his “notoriety as a practitioner of cunnilingus.”

“Rude Talk in Athens: Ancient Rivals, the Birth of Comedy, and a Writer’s Journey Through Greece,” chronicles Smith’s travels to Greece and the ancient past, emerging with musings on what makes for literary posterity. It’s a rich subject when considering Ariphrades; as far as historians know, nothing of his work has survived to the present day.

Smith discovered the playwright while researching a book he meant to focus on the Greek philosopher Epicurus. He came across a reference to Ariphrades made by a playwright of more enduring fame, Aristophanes. Intrigued, Smith switched gears. Reading “Rude Talk in Athens” is like taking an epic tour of Greek drama and politics with an irreverent expert in the driver’s seat. Smith spoke to The Times via a video chat about fame, the political power of comedy and why oral sex is tantamount to revolution. An edited version of our conversation follows.

How far did you get with your original idea about Epicurus before you realized the real story was elsewhere?

I had a whole book proposal. I’d spent six months to a year working on it, and my agent said, “Mark, I just don’t want to read a chapter about nipple clamps.” She had a bunch of notes. Once I found out about Ariphrades, that was really pulling me the whole time. I explained it to her and she said, “Don’t try to write a proposal. Just write the book and then we’ll just see what we can do.” I wrote it on spec, as they say.

You cover a lot here: Ariphrades, contemporary Greece, the idea of a literary legacy. How did you find the scope of the book?

I got to a point where I said, I have nothing more I can add that’s not just repetitious. There’s almost no information about the guy and there’s almost no information about ancient Athens, as much as we think there is. Then I went back through it; there were some things I took out, like — you’re not going to regret this being cut — a personal history of my experiences with cunnilingus. More and more, I started thinking about what it means to be a writer in a culture and a civilization that falls, like our empire is crumbling. We’re in Ariphrades’ position. Who knows? In 1,000 years, will any of our work be around? Highly unlikely.

The first time I read Aristophanes’ play “The Frogs,” I was struck by how much it referenced other writers of the period, which felt very modern to me. Did any of these metafictional touches surprise you?

When I went and saw “The Clouds” at Epidaurus [a still-operating ancient Greek theater] — there are jokes that are thousands of years old and they’re still landing. People are making fart jokes and boner jokes. The great thing was, those writers that Aristophanes would have been slagging [were] in the audience. I guess the only equivalent we have now are roasts. Everyone is in on the joke. It did surprise me that it’s still funny. The things that we laugh at have been funny forever.

Did writing about ancient humor end up changing the way you experience comedy?

Because my novels are comedic, they’re just dismissed: “Oh, it’s a funny novel. Can’t have any ideas in it, I don’t even need to read it.” You start to think, it isn’t a new thing that our society dismisses comedy as easy or facile. Throughout the history of the world, people say, “Oh, it’s easy to make people laugh, and it’s hard to bring about catharsis through drama.” It made me go, “Yeah, well, f— you, because you haven’t tried it!”

Comedy’s important. That’s why there are the two masks, drama and comedy. You need both. That we can still laugh at the same jokes now is amazing. I don’t know if a revival of “Hamilton” 2,000 years from now is going to resonate with people, whereas Aristophanes still does.

Eagle, food writer, chef and fermenter, Skypes in with advice on making an intercontinental lunch, but no recipes.

You write in the book about Sarah Cooper and Hannah Gadsby in the context of comedy and politics and history. Are there any other comedians you thought about while writing?

I like comedy and I watch a lot of it and I read a lot of it. And there’s some writers who, like Carl Hiaasen, are still funny, still political. There’s this idea that this poet, Aaron Poochigian, talks about — he did a translation of Aristophanes’ plays and he talked about patriotic obscenity. We need to be able to say “[screw] you” to the people in power. That’s what Aristophanes and the Greek playwrights did.

I think about people like Chris Rock or Trevor Noah or John Oliver, who aren’t just making typical jokes but really speaking to the political moment. That connects right back to Aristophanes, and from there to Molière to Joe Orton in the ‘60s to what’s happening now. There is a throughline.

You touch on people in positions of authority suppressing different kinds of knowledge; I couldn’t help think of the current pushback on critical race theory.

Hopefully I’m not Cassandra. I think we’re seeing the death rattles of white supremacy and the patriarchy. That’s my hope. But they’re not going down without a fight. So with any kind of monster, you’ve got to drive the stake through its heart before it finally stops screeching.

Your focus in “Rude Talk” on the juxtaposition of freedom and pleasure also seems very relevant to American politics as well.

Pleasure, and particularly female pleasure and I would say homosexual pleasure, terrifies the patriarchy. We call ourselves a Christian nation, but it’s more like we’re a patriarchal nation. I think this goes right back to why Ariphrades was attacked. It destabilizes the core myths that the people in power are trying to impose on the population.

Once that gets rattled, they start getting scared. It’s just a domino effect. And hopefully, it brings them down. I made a claim for that at the end of the book. Let’s just have more pleasure, more sex, more fun. It’s the best way to have a revolution. It’s better than guns.

Carroll is author of the novel “Reel,” the story collection “Transitory” and the nonfiction work “Political Sign.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.