Review: How weird women became ‘witches’ in a fierce debut historical novel

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Manningtree Witches

By A.K. Blakemore

Catapult: 320 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Seventeenth-century England was a world turned upside down. Arguments over religion erupted in violence. Calvinists wanted a stripped-down Christianity wholly determined by literal readings of the Bible. The Church of England had adopted Protestant doctrines but still incorporated Catholic rites. Calvinists believed in the equality of believers but not women, whom they saw as responsible for original sin.

When civil war broke out in 1642, the ensuing chaos was disastrous: displaced people, outbreaks of bubonic plague, typhus and other deadly diseases, famine as a byproduct of war. The 1649 beheading of Charles I cut the figurative head off patriarchal society.

In her new novel, “The Manningtree Witches,” A.K. Blakemore explores the consequences of that chaos for a group of village women through the viewpoint of a narrator named Rebecca West. West, a true historical figure, was among those prosecuted in Essex. Blakemore’s novel adheres to these events but fills in the lacunae in the documents.

Several of her women stand outside their communities in various ways. Mother Clarke dispenses folk magic; Rebecca’s mother, Jane, is described by her own daughter as “Jade. Pot-companion. Mother”; Rebecca herself is an outlier for being literate. None of them are married. Liminal spaces are dangerous for women, never more so than under Calvinism.

Mother Clarke is old and going blind from cataracts. She has lost a leg and her hands shake with palsy. While Rebecca sees Mother Clarke as a “withered and slatternly old woman,” her neighbors perceive her as “cunning,” capable of making small charms. Rebecca assumes it’s the widow’s “web-in-the-eye” that draws folks. “Beyond the uncanny way it makes her look — like a fairy came along and scrubbed the meats clean of spots — people get terribly superstitious about such things as cataracts, and choose to believe that God would not be so cruel as to rob an old woman of her earthly gaze without equipping her with a spectral one, to say sorry.”

The passage indicates a theme. Women’s bodies are described in extensive sensory detail. Rebecca’s mother has thin lips; she observes “how her teeth are stained from chewing tobacco, how the wet root of her tongue jostles.” The women in church “fan themselves with their handkerchiefs, churning up bemingled emanations of rosewater perfume, womb-clot, sweat and cinders.”

‘Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch,’ historical fiction about Kepler’s mother, is Galchen’s first novel since 2008’s ‘Atmospheric Disturbances.’

In a culture that prioritized the spirit over the flesh, witch-hunting manuals were obsessed with the body of the witch. Catholic and Protestants alike examined witches’ physical aspects as if by speculum.

When a newcomer arrives at Sunday services, Rebecca acknowledges that Matthew Hopkins is handsome, “[b]ut there is something about him slant and insubstantial, as though all the dramatic outfitting houses none of the usual human meat. Black boots, black gloves, black doublet, black cloak, black ringlets and then a white face floating lost in the midst of this funereal confection.”

Rebecca’s instincts are proved correct. Hopkins, who in actual history was called the Witchfinder General, publicly blamed the litany of community tragedies on the work of witches. Absent a working government, he operated without oversight. He began that campaign in the village of Manningtree.

Blakemore, who also is a published poet, brings both beautifully crafted sentences and a thorough understanding of Hopkins’ theology to her fascinating novel. Her narrative alternates between the first-person account of Rebecca West and a third-person perspective that makes readers into witnesses.

In a scene that precedes the women’s eventual arrests, Blakemore conveys Hopkins’ attention to physical details in a way that also foreshadows violence: “He removes the apples from the basket carefully, one by one, inspecting each... He throws one experimentally on the fire and crouches low by the hearth to watch it burn. There is an odour, though barely detectable — sweet and acrid at once, like horse dung. The dermis slowly blisters then cracks, the juices sizzling out, and within minutes all that remains is a charred core with two scorched frills of leather, like the brow bones of a death’s head.”

Witchcraft, real or imagined, has become a somewhat trendy tack among writers turning over the legacies of patriarchy, but Blakemore is no dilettante here. Based on my own dissertation work on the topic, it’s clear that the author is deeply conversant in the historiography of English witchcraft as popularized by historians such as Keith Thomas and Lyndal Roper. Her characters plumb the taxonomy of the persecuted with precision — from Mother Clark, the archetypal “beggar witch,” accused of cursing those who refuse to help her, to Rebecca’s mother, Anne, the “midwife witch,” who takes the blame for devastating levels of child mortality.

Taschen’s “The Library of Esoterica,” a series that begins with “Tarot” and “Astrology,” honors the history of mysticism and its democratization.

Anne has been a difficult woman most of her life, and she offends neighbors often. Rebecca is arrested because neighbors assume mothers pass on witchery to their daughters. For Hopkins, a witch’s body bore physical signs of her alliance with the devil, and part of each interrogation was “pricking” — probing with needles for growth, especially on the genitals. Though torture was technically forbidden under English law, this was not; nor was sleep deprivation. The interrogator’s words came up against human flesh. The command accompanying the torture was always the same: “confess.”

Torture produced confessions but not the truth. Blakemore’s clear agenda is to give these silenced women a voice, and in fiction, she can thrust herself into Rebecca’s consciousness. The discipline of history doesn’t allow that, which often leaves it gesturing toward the silencing without being able to give it voice.

Rebecca’s ability to read and write is important, and not only in serving Blakemore’s goals. She loves words, and the echoes of her reading appear in her vocabulary. But she also sees that what Hopkins is asking her for are simply words, words she can speak without believing them. Whether she will speak them, and what they would signify, becomes another theme of the novel. Among its perverse delights is the employment of the language of witch-hunting manuals (“inspissated,” “deliquesce”) to drive home the bodily obsessions of the trials.

One other recent witch novel, Rivka Galchen’s “Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch,” wrestles with some of these same questions, turning on the intellectual battle between early scientist Johannes Kepler and those who had arrested his mother. Galchen sought to give a voice to a woman whose true nature can only be gleaned in occasional spaces in the court records.

Blakemore also depended on court documents and contemporary sources. In charges of witchcraft, the exalted words of male intellectuals were branded onto the feminine body. Much of it — accusations of penis-stealing and insatiable lusts — was clearly displaced neurosis over sexual desires that interfered with celestial communion. But as Blakemore shows in her brilliant novel, the spiritual life many of them extolled was as slant and insubstantial as Matthew Hopkins.

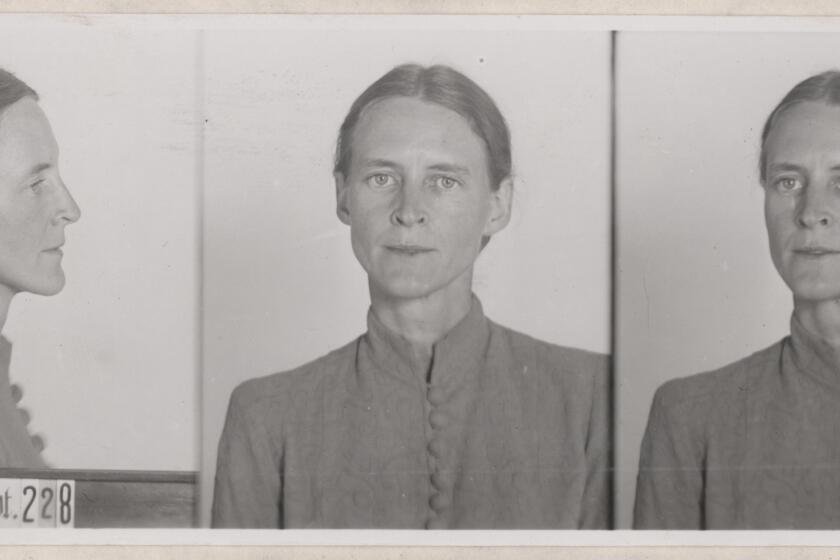

How a novelist cracked the real-life story of her Nazi-fighting great-great-aunt.

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.