It’s high time to put ‘Women in the Picture,’ an art historian argues

- Share via

On the Shelf

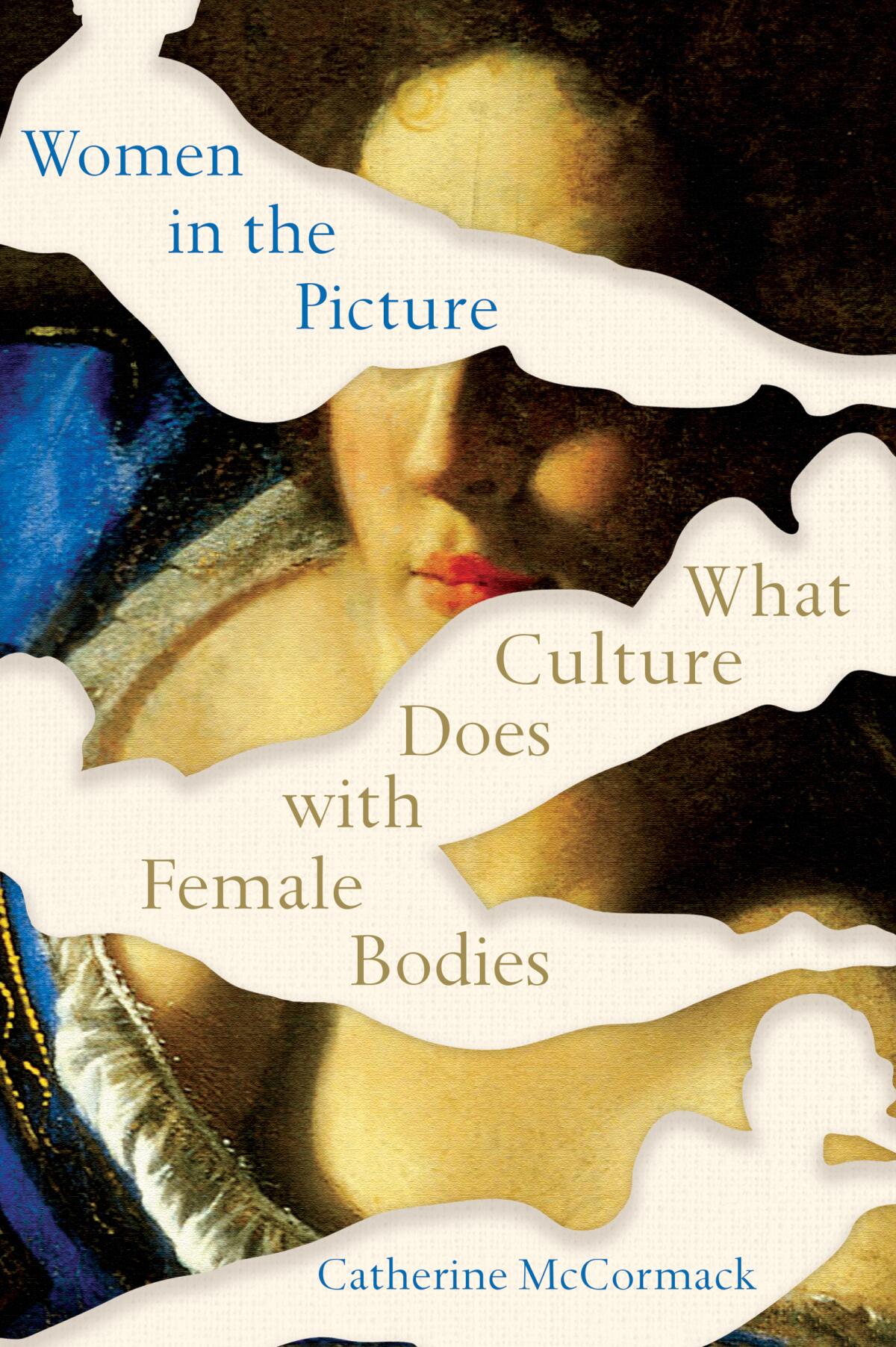

Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies

By Catherine McCormack

Norton: 240 pages, $23

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Catherine McCormack and I had long been commenting on each other’s Instagram posts about feminist art when we finally decided it was time to sit down and have a Zoom meeting. She is a course director of the women and art study program at Sotheby’s London, and the occasion was the publication of her new book, “Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies.” The chaos of three time zones and daylight saving couldn’t stop us from deconstructing the lens of art history, which, McCormack argues, wants to confine women to four categories: Venuses, mothers, damsels or monsters. The misogyny, she writes, is so pervasive that we simply can’t see it anymore. “Women in the Picture’s” work is to help us regain our vision. Our conversation has been edited.

What made you want to write an entire book about women in art? What was the straw that broke the camel’s back?

The catalyst was personal and professional. I was a grad student at the time. I got pregnant, and I noticed immediately that I was treated differently in the eyes of the academic department. It felt like I had been spoiled for this great career success. All these things, in the sense of the personal becoming physical, started to enter my thinking.

Kate Zambreno’s process is rumination and frenzy. That’s how she completed “To Write as if Already Dead,” an homage to the late writer Hervé Guibert.

It was the same for me. When my son was born, as a freelancer, I had no prescribed leave. Everything difficult about trying to make a creative career was amplified by motherhood. But female artists — mothers or not — have always faced systemic obstacles. I don’t think many people realize this.

In the U.K., it wasn’t until 1768 that there was an academy of art, and two women were among the founding members. But there wasn’t another woman fully elected until the 1930s, and that hiatus — it’s really a chasm — stops women participating in cultural production. We can only assume that this was because women posed a threat to the patriarchal system, representing women as a means to police their behavior. This is not a conspiracy theory; it is an objective truth.

It’s similar to the medical profession. There was this determination to keep women from knowing their own bodies and having the means to represent their vision of themselves, their perspective on life and their perspective of male bodies. There was a real paranoia about women getting to look at naked male bodies in the life class, which was the foundation of artistic study.

It’s an admission of real power — the power of who gets to look — that shapes powerful discourse about how we understand ourselves and create templates for living. There are only 21 paintings by women in the National Gallery in London. That’s from 1300 to 1900. There doesn’t seem to be any major work being done to remedy this. There was one Artemisia Gentileschi show, which was fabulous, but for so long ... we’ve not really been seeing things.

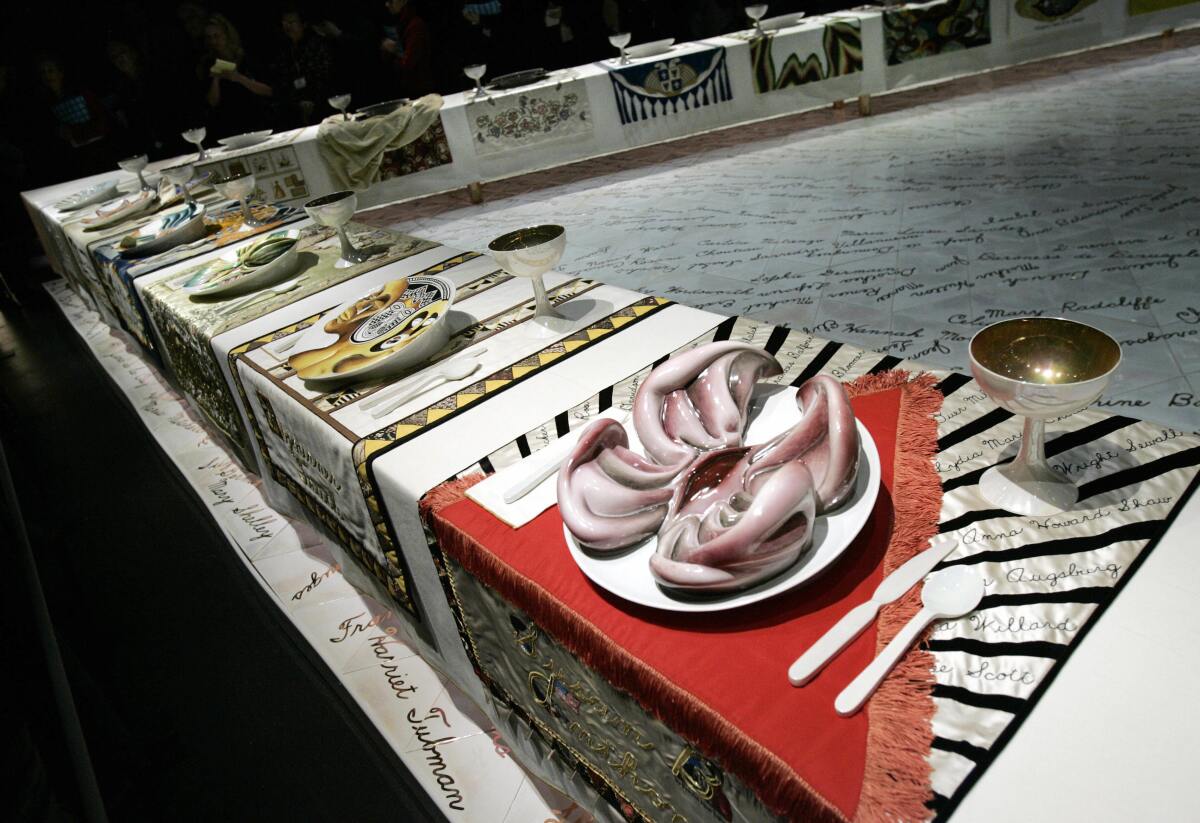

To me, it seems like there’s so much work still to be done. For instance, the Judy Chicago retrospective at the deYoung in San Francisco discusses the issue of “essentialism,” or the idea that women shouldn’t be represented by their anatomy, in the information for “The Dinner Party.” But to see a vagina, a vulva, a bloody tampon, hanging in an art museum is still explosive to me. As you write in the book, “a woman’s body is always taboo.”

What I see Judy Chicago doing, through the use of the vulva imagery, is creating an alternative symbolic order to the phallus. The phallus is the signified order in our language. That’s been so normalized. That’s why we don’t see the mythological rapes, we only see a woman holding a sword. I can see why some women don’t want to identify with the materiality of the body, but by not engaging in that debate, it cancels powerful inquiry into things like menstruation and birth.

The Desert X biennial in and around Palm Springs has released its artist lineup, led by Judy Chicago. She will stage her work near the Living Desert.

There’s so much to talk about right now, and I really want to talk about midwifery —

... and witches.

There’s a photograph in the same show of a woman pulling out a tampon. I took a picture of it and posted it on social media, and I took a close-up of the Georgia O’Keeffe plate, and most people were like, “Yay, Judy Chicago.” But some people were disgusted.

Oh, yes. Let’s not forget that many male artists have made work out of their bodily fluids, like Vito Acconci and Andres Serrano, and been accepted into the canon. A man can make art about his semen, but when women artists make art about menstruation, it becomes taboo. Not all women bleed — but everyone came from a woman that bled. The universality of that experience makes it too much to eclipse as a valid subject matter.

You mention in the book that Sojourner Truth is the only woman of color in “The Dinner Party,” and discuss the Venus figure as a deeply racist and misogynist beauty standard. I love that the book ends with Kara Walker’s 2014 work “A Subtlety …,” a giant mammy sphinx made out of sugar installed in Brooklyn’s old Domino sugar factory. I was lucky enough to see “A Subtlety ...” and it was just awesome — I mean, there’s no better use for the word “awesome.”

But I did have doubts about my right, or my privilege, to write about the sphinx as a white woman. Thank you so much for noting that it ends the book. It might be closing the chapter but it feels impossible to contain it. It’s there to trouble us. I recognized my own inability to encapsulate the work. The way it oscillates between monumental grandeur that elevates the body of the invisible woman of color who is exploited, but also this pronounced sexuality with this intentionally oversized vulva. To pin it down would be another kind of violence.

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

I love the idea of the sphinx being an opening, not an ending. I felt the same way about a painting you mention, “Lilith,” by Sylvia Sleigh — who portrayed the biblical woman . . .

With a penis.

Sylvia Sleigh painted it in 1976 — and the idea of Lilith as trans is just very exciting. I think trans representation in art is so thrilling and beautiful.

I’m so glad I could include that Sylvia Sleigh image, because it highlights that there were these representations that challenged the gender binary in the 1970s that have been forgotten. There’s an antagonism to second-wave feminism — it has this TERF [trans-exclusionary radical feminist] identity now — but it’s evident that these conversations were happening then. It’s an invitation not to overwrite the work of the Second Wave. Feminist art history cannot be a monolith. It is a broad church. Seeing different types of bodies is wildly exciting to us, it brings us back to common ground.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.