Review: Can acting change the world? Isaac Butler argues that it already has

- Share via

On the Shelf

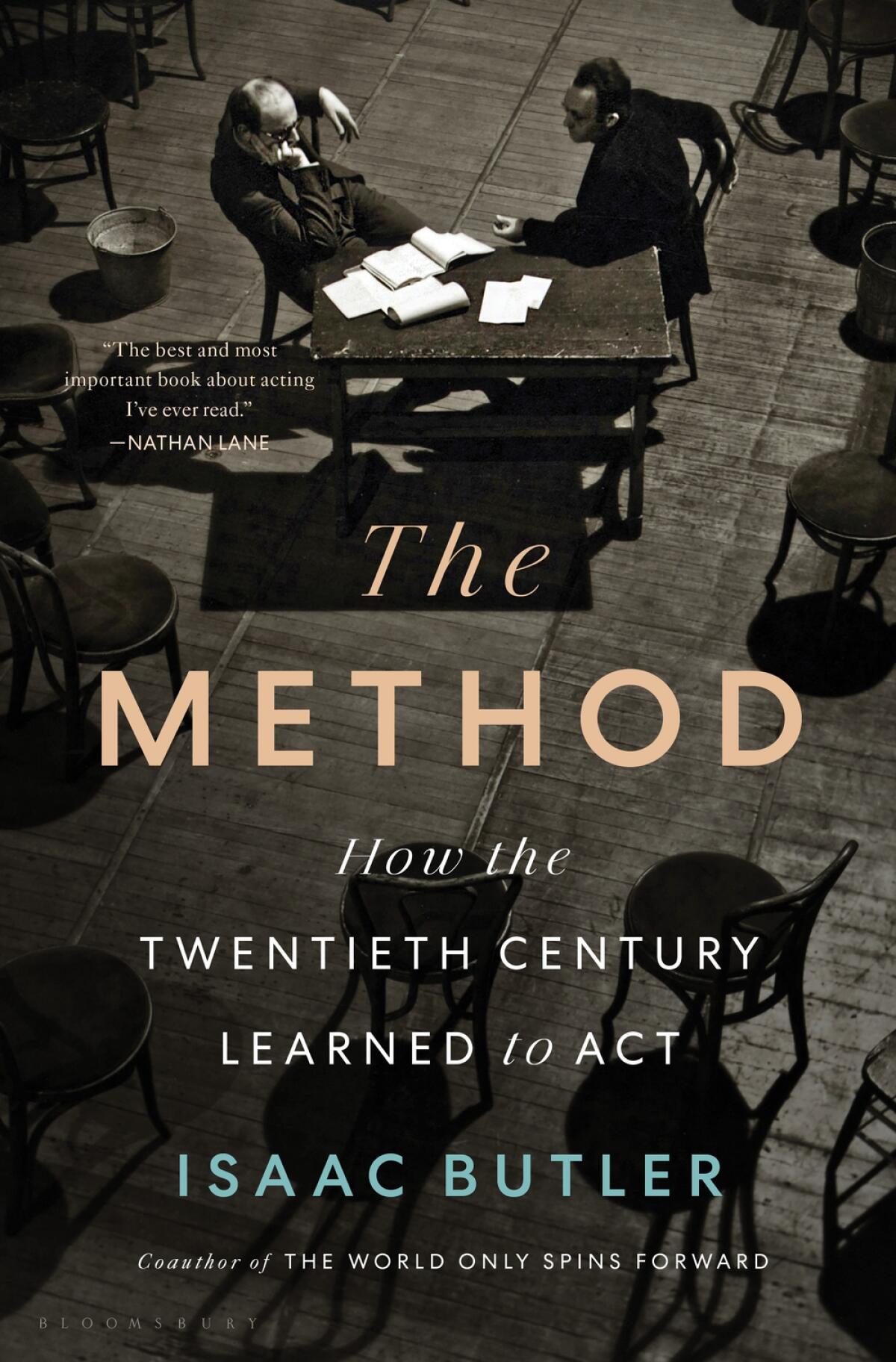

The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act

By Isaac Butler

Bloomsbury: 512 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Since the first commercial movie screening in Paris in 1895, spectators have been mesmerized by the screen. Yet audiences and actors alike are hard-pressed to define what makes a good performance. We simply know it when we see it. Like a good book or song, a solid acting performance resonates with what we recognize as universal truths about our own shortcomings and successes, faults and fortunes. This wasn’t always the case with acting.

Isaac Butler’s engaging and meticulously researched history, “The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act,” chronicles the way presentational acting — in which the spectator is aware the actor is performing — shifted to perezhivanie, or an actor experiencing her role so truthfully that the audience forgets she is acting.

Butler refers to this transformation as a “revolution” that began in 1898, when Konstantin Stanislavski, largely influenced by his contemporaries — Tolstoy, Chekhov and literary critic Vissarion Belinsky — began a decade-long dive that produced the Stanislavski System, in which an actor could reliably employ perezhivanie whenever called upon to perform. Although the father of modern acting revisited his System throughout his life, Butler distills its earliest version into two “principles”: the use of an actor’s life experiences and the breakdown of a role into bits, with the aim of “accomplishing each of these bits as truthfully as possible.”

Like a good 19th century omniscient novelist, Butler hops seamlessly among his characters’ points of view while recounting their lives and times. He sets the stage of Russia’s victory over Napoleon in 1812, comparing it to “Elizabethan England or the United States post-World War II,” gracefully balancing on the right side of that fine line between contextualizing and condescending to the reader. With literacy rates growing, the time was ripe to rebel against the star-based theater and place the actor on equal footing with the director and the play, especially as playwrights caught up with naturalism and began exploring timely themes.

Dana Stevens and James Curtis, authors of “Camera Man” and “Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life,” argue for the silent film star’s enduring appeal.

The stakes heighten as the System travels to America. A newly formed group, wanting an alternative to the melodramatic fare popular on Broadway, embraced the System to shepherd a new theater that reflected the Depression-era struggles of America. The folks who created what became known as the Group Theatre agreed their goal was truthful, realistic acting. However, they soon disagreed on how to adapt Stanislavski’s System.

Those arguments live on today: Does an actor use her personal memories to emote? In which case, what part does the imagination play in building a character? Does one rely solely on research of her character and study of the setting and historical context, or what Stanislavski referred to as the “given circumstances” of the play (or script)? Is it possible to go too far in this direction, to the point where the actor begins behaving like her character even off the stage or screen?

The most contentious disagreement fell between Group Theatre director Lee Strasberg and soon-to-be master teaching rival Stella Adler. Strasberg emphasized Stanislavski’s pathway of affective memory — a type of emotional recall that relies on one’s own experiences instead of the character’s — and this Stella abhorred. After studying with Stanislavski herself in 1934, she returned to the Group with the news that he had disavowed affective memory. Adler began teaching the Group’s actors, and Harold Clurman, not Strasberg, directed their next play, Clifford Odets’ masterpiece “Awake and Sing!” Strasberg defensively claimed it was his “method,” not Stanislavski’s System, that the Group followed. What would later become popularized as the Method would henceforth be tied to Strasberg.

This makes Butler’s main title, “The Method,” set against the book’s cover photograph of Strasberg giving notes to actor Morris Carnovsky, problematic. It casts Strasberg as progenitor of modern acting craft and narrates the story of modern-day acting through the lens of the Method. Butler even refers to “Awake and Sing!” — with which Strasberg was not involved — as “the first full-length Method play.”

Describing how the Method arrived in Hollywood, Butler writes that when the Group Theatre finally “gave in and went to Hollywood, they would take their method with them,” with actor John Garfield leading the way. “After learning the Group’s method from Strasberg,” he continues, “…Garfield is often remembered as the actor who helped pave the way for Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando and the Method revolution.” Like any actor worth his salt in the 1950s, both Clift and Brando attended Strasberg’s Actors Studio. But in fact neither learned to act from Strasberg.

To his credit, Butler dedicates a generous amount of his narrative to the Group’s schism, calling it an “unresolvable dispute.” And yet he capitalizes on the way “the Method” caught the popular imagination as the revolutionary style — and therefore became the term that comes most readily to the lay reader’s mind. In doing so, he conflates the Method with Stanislavski’s System, which is akin to writing a history of rock ’n’ roll featuring Elvis Presley on the cover, crediting him as creator of the genre, and referring to rock interchangeably with its progenitors, gospel and blues.

Marlon Brando, a two-time Academy Award winner who spent much of his career shunning the Hollywood establishment yet earned its enduring admiration through muscular, naturalistic performances that transformed the craft of acting and led peers and critics alike to hail him as the finest actor of his time, has died.

Structuring his book like a biography, Butler traces a straight line from the birth of the Method — which was actually the birth of the System — to its demise in the 1980s. Throughout, his running theme iterates Stanislavski’s once-radical concept of imparting the truth through acting. Butler writes: “The Method’s story no longer belonged to just a few individuals. ... It was instead the story of Hollywood itself. Whether an actor was trained by Strasberg, or Meisner, or Adler ... the stylistic goal was the same. ... Running through them all was that there was a truth about American life, a protean muck that had previously been buried deep underground.”

Butler alights on Watergate as a disillusioning American moment, during which “the Method could bring audiences closer than ever to the internal conflicts and pains of living in Nixon’s America.” By suggesting that America’s moral turpitude could be processed through acting, Butler taps into the System’s greatest contribution: that the actor creates “an empathic connection between spectator and character,” amplifying the transformative power of story. Despite his conflation of terms, Butler’s history is an indispensable account of a revolution in acting that ramified beyond the theater, even as he vacillates on whether the Method ever truly “died.”

There is in fact an answer: What has not died is the System. In his afterword, Butler drives home the central objective of the System: Authenticity is the actor’s duty to her audience. He writes that in rehearsals today, Stanislavski’s original precepts remain the building blocks for actors. Director and actor will “talk about beats and structure a scene by its actions, will try to create staging that is informed by the characters and their needs. ... You’ll hear them say the words ‘given circumstances.’” These tools equip the actor to transmit the human condition, which can only be done by telling the truth. Butler’s book delivers on this honest gospel. The truth in art transcends any master or methodology. The truth directly meets the human spirit.

Domestic drama: Lee Strasberg’s family continues the legacy of instruction, despite some friction

Ochoa is a cultural critic and the author of the first biography of Stella Adler, “Stella! Mother of Modern Day Acting.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.