Review: The predator’s wife: A dark debut novel with a #MeToo gender twist

- Share via

On the Shelf

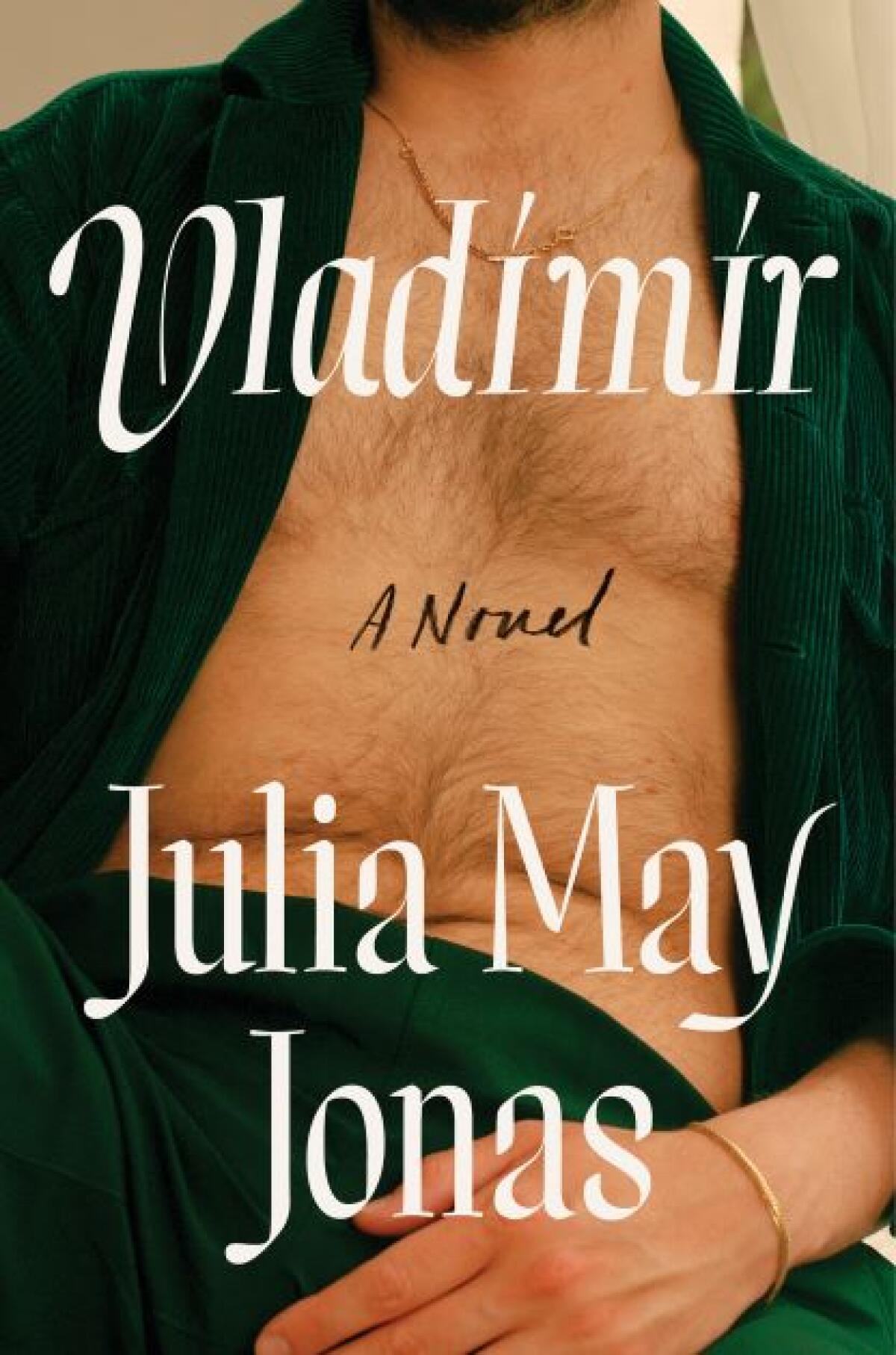

Vladimir

By Julia May Jonas

Avid Reader: 256 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

What is more delicious than the despicable narrator? Particularly the charming and poised variety, like “Lolita’s” Humbert Humbert, whose obsession compels us in ways we know are shameful. Julia May Jonas’ energetic debut novel, “Vladimir,” introduces us to such a character, though hers is a rare subtype: a female English professor whose husband has just been accused of sexual misconduct by multiple students.

“When I was a child, I loved old men, and I could tell they also loved me,” says our unnamed antiheroine, opening the book with a few paragraphs about how much she basked in their affection as a girl, before continuing: “What I like most about old men now, however, and the reason I often feel that perhaps I am an old man more than I am an oldish white woman in her late fifties (the identity that I am burdened with publicly presenting, to my general embarrassment) is that old men are composed of desire. Everything about them is wanting.”

Behold, the new repulsive narrator, a post-menopausal white woman who might be complicit in her husband’s crimes. “Now my husband was abusing his power,” she scoffs, “never mind that power is the reason they desired him in the first place.” The couple had an arrangement. “I enjoyed the idea of his virility, and I enjoyed the space that his affairs gave me. I was a professor of literature, a mother to Sidney, and a writer. What did I want with a husband who wanted my attention?”

Amid this crisis, a new hire comes to town: a young male novelist named Vladimir. Our narrator is smitten by his good looks and confidence, but what really attracts her to Vladimir is her envy of his writing. She is the author of two novels, the first a success and the second a dud, but hasn’t published in years.

Capturing both the love and suffocation of motherhood, “The Lost Daughter” deals in the kind of human complexity usually reserved for serial killers.

“I have watched writing the female experience — particularly the motherhood experience (the subject of my second book) rise and reach praise and prominence in the past decade,” she laments. “I do not think I was ahead of my time; I think I wasn’t as unapologetic as this new crop of writers are…. They don’t shy away from talking about the banality of existence that comes with being a mother.”

While reading Vladimir’s novel in the library (“to do so in my office would be humiliating”), she is “overwhelmed with a mixture of genuine admiration and seething jealousy.” Does she want Vladimir, or does she want to be Vladimir? The wonder of this novel is in the answer: She wants both.

She goes out to a cabin and writes all night, struck with an urge she hasn’t felt in years. “Oh, it was him,” she says. “It was all because of him, I knew. Him and his book and his body, and the way he spread his legs and looked at me in the black glass of the window ... I wrote until the sun waned.” Her sexual desire for Vladimir is real enough, but what it rekindles in her is more essential: the drive to create.

Jonas, with a potent, pumping voice, has drawn a character so powerfully candid that when she does things that are malicious, dangerous and, yes, predatory, we only want her to do them again. The narrator’s disdain toward her husband’s accusers — her unwillingness to allow that he has done something wrong by sleeping with them — raises difficult questions. For her, there is no abuse of power, because sexual attraction is always about power. She tells us that she would have thrown herself at her professors had she not been so timid. “I desired them because I thought they had the power to tell me about myself.”

“My Dark Vanessa” is the latest and most unsettlingly effective book in a timely genre.

The novel opens with the narrator gazing upon Vladimir’s golden, shackled body, so it’s not exactly surprising when she pilfers a few Seconals from her daughter’s girlfriend’s toiletry bag. Jonas is obviously keyed-in to the waxing and waning of the #MeToo movement. I suspect that she’s kept up with recent work by such writers as Amia Srinivasan and Maggie Nelson, who suggest that moralizing about consensual sex can be a deeply limiting and desire-annihilating enterprise.

The climax of the book is expectedly dramatic, and the symbolism of what happens to our narrator and her husband is a bit heavy-handed. By the end of the book, the narrator comes face-to-face with one of her husband’s accusers.

At first, it seems we’re headed for a tidy conclusion — a flash of understanding, a shift of allegiances. But as the philanderer’s wife spins out a presumptuous account of the woman’s backstory, it becomes clear that Jonas is after something else. “Perhaps that is what she thinks,” the narrator concludes. “Or perhaps that is what I imagine the young woman ... might think.” Though it intimates an opportunity for redemption, even contrition, the narrator’s interest in the accuser (and potential victim) is, in the end, purely literary.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

Kate Zambreno’s process is rumination and frenzy. That’s how she completed “To Write as if Already Dead,” an homage to the late writer Hervé Guibert.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.