How a Stanford med student used her experiences to write a heist caper and score a Netflix deal

- Share via

On the Shelf

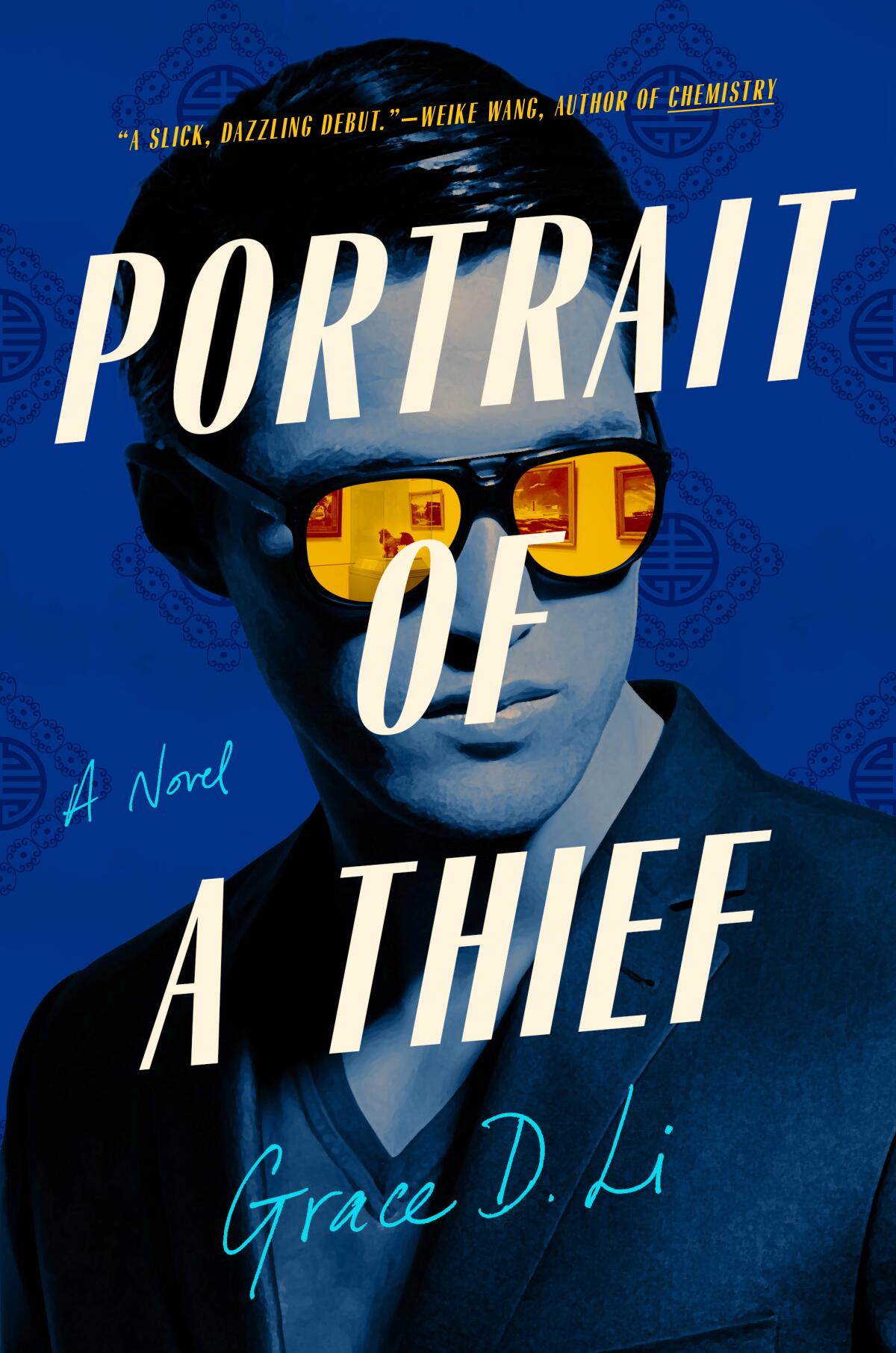

Portrait of a Thief

By Grace D. Li

Tiny Reparations: 384 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit as Grace D. Li was finishing her first year of medical school. She found herself stuck at home, attending classes on Zoom and barred from setting foot in a hospital.

“It was the most devastating medical catastrophe of the last century, and there was nothing I could do to help,” she recalls.

Frustrated, the 26-year-old Stanford medical student turned to a passion project waiting on her computer: a novel she had started a few years earlier. The result is “Portrait of a Thief,” a heist caper out this week that turns on breakneck action, fast cars and a thoughtful exploration of Western colonialism and the complexities of Chinese diaspora identities.

The story of why Li turned to fiction in a crisis — and pursued two seemingly opposing career paths — has as many twists and turns as Li’s novel, born from her experiences as a scientist and writer, American-born and ethnically Chinese.

For Li, who starts her third year in medical school this summer, her career choices aren’t contradictory. “Despite the differences between medicine and writing,” she says during a recent conversation, “both require thinking deeply and thoughtfully about the world and the people in it.”

The premise of “Portrait of a Thief” is deceptively simple. The novel’s main character, Will Chen, is a Harvard art history student who witnesses the theft of Chinese artifacts from a campus museum by an organized team that leaves him an intriguing calling card. That experience and a racist encounter with cops investigating the crime propel Chen to reach out to the chief executive of a shadowy Chinese government-backed conglomerate. The CEO offers $50 million to Chen and his hand-selected group of students to steal five bronze Zodiac heads that once adorned a fountain in Beijing’s Old Summer Palace.

As improbable as that setup may sound, Li says inspiration for her heist novel came from a true story.

After graduating from Duke University with a major in biology and a minor in creative writing, Li had taken a two-year assignment with Teach for America in New York. She taught biology in the Bronx and ran a high school’s first creative writing program. When she was in the middle of applying for medical school, she read a newspaper story about the heist of Chinese jade and gold artifacts from a museum in southwestern England.

Li, whose parents emigrated from China in the 1990s, says the story “struck me deeply.” Digging deeper, she learned that such robberies, from museums in Sweden, Norway, England and France, had started almost a decade before. Thieves targeted priceless Chinese antiquities that had been pilfered in 1860 by French and English invaders who ransacked and looted the Old Summer Palace, a constellation of 200 ornate palaces, pavilions, courtyards and gardens, before burning the complex to the ground. The three-day conflagration sparked China’s 21st century challenges of the provenance of artifacts displayed in Western museums, a bid by wealthy Chinese and government-backed corporations to snap up pilfered items at auction, and speculation that treasures lifted from European museums over the last decade had been “stolen to order” by those intent on repatriating the art to China.

Li says the swirl of stories “made me wonder if I could have been one of those thieves.” The tantalizing possibilities tapped into her love of popular culture, including heist movies and the “Fast and Furious” film franchise, and ignited her novel.

Bethanne Patrick’s April picks include highly anticipated novels from Jennifer Egan, Emily St. John Mandel, Don Winslow and Douglas Stuart.

Although “Portrait” reflects Li’s interests, like a good scientist, she filled in the gaps with research. She studied Chinese art history, how to make bronze sculptures and the collections, locations and layouts of European museums that housed some of the disputed artifacts. At Stanford, she soaked up contemporary art and museum operations while serving as a pre-pandemic tour guide for art museums on campus. She also found mentors and community at the university’s Medicine & the Muse Program, which supports diversity and integration of the arts and humanities into medical education.

Li’s hard work paid off: Editor Amber Oliver acquired “Portrait” in 2021 for Phoebe Robinson’s Tiny Reparations Books imprint. As one of Stanford’s MedScholars, Li received time off and funding to finish her novel, which she did during those frustrating early days of the pandemic.

Li will join a small but distinguished club of doctors who write crime fiction. Arthur Conan Doyle, Michael Crichton and Tess Gerritsen all balanced medical careers — using their left brains — with right-brain creative fiction that makes readers’ blood run cold. Li recognizes the debt she owes to such pioneers who “helped me realize a career like this was possible.”

Buoyed by that knowledge and encouragement from her editor, Li leaned into her characters who are amateurs but also heist novel archetypes. There’s Chen, the mastermind; his sister Irene, a public policy major who can con her way out of anything; Irene’s roommate Lily Wu, the getaway car driver and a Duke student who likes street racing; Alex Huang, the team’s nascent hacker and an MIT dropout; and Will’s best friend Daniel, a premed student who has an inside track as the son of an FBI agent assigned to art crimes.

Although Li uses genre archetypes and tropes, she didn’t rely on them to tell a bigger, more personal story about the wide range of identities within the Chinese diaspora.

“Everyone thinks that Chinese identity is a monolith,” she says, “but there’s enormous diversity among Chinese Americans in terms of language, personal identity, socioeconomic status and how they think of themselves in relationship to China. There’s no one idea of what it means to be Chinese.”

The Great Chinese Art Heist crew, as the students dub themselves, mirrors that reality. Four are Americans, from California, New York and Li’s native Texas; Beijing-born Daniel is a naturalized U.S. citizen. Li’s students are idealistic enough to compartmentalize their crimes as a reckoning with Western cultures and colonialism. But they also recognize that the thefts will bring enormous wealth and the ability to break free from crushing student loans and, more important, the structured lives mapped out by their families — “the future carved open,” Li writes, like the precious artifacts they steal.

Poet Amanda Gorman joins book club readers at the Festival of Books.

“Portrait” attracted enough early buzz that Netflix picked up the book for a television adaption, with Li serving as an executive producer. It’s an exciting but liminal space for a medical school student with a commitment to health equity for underserved patients and a book tour that includes an April 24 appearance at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books. She says of her debut, “I hope ‘Portrait’ invites conversation about the ways that history continues to influence the present day, as well as illuminates the complexities and joys of the Chinese American experience — all wrapped up in a story that’s as exciting as a heist.”

Li also shared that she’s starting a new novel. Continuing to blend art and science, she plans to set it at — where else? — Stanford’s medical school.

Woods is a book critic, editor and author of several anthologies and novels, most notably the Detective Charlotte Justice mystery series.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.