How Trump’s election set ‘Less’ author Andrew Sean Greer off on a road trip — and a sequel

- Share via

On the Shelf

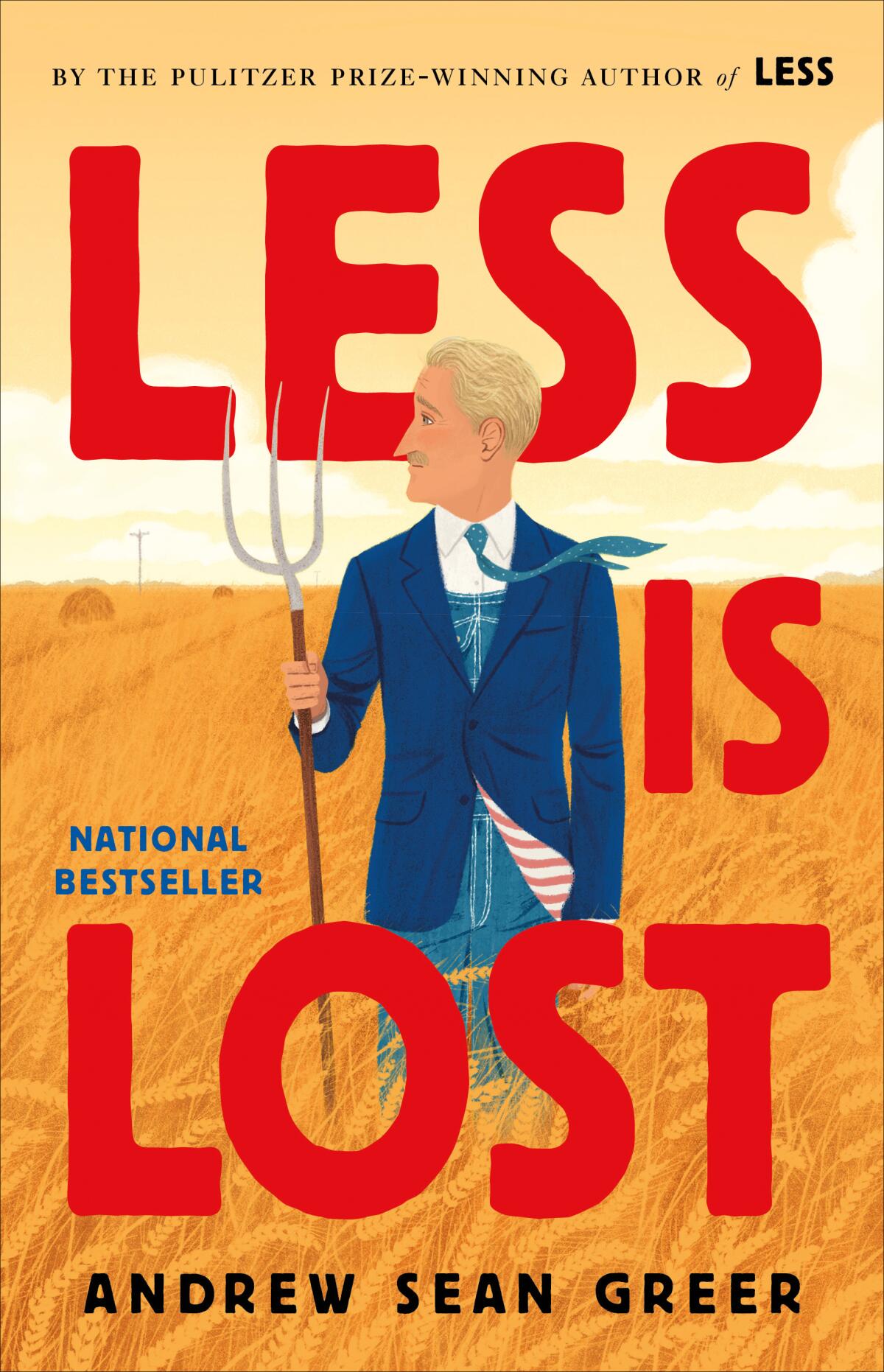

Less Is Lost

By Andrew Sean Greer

Little, Brown: 272 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In 2011, I attended a writers’ dinner. The best part, aside from the fact that it was on the Amalfi Coast, was that I was seated next to the novelist Andrew Sean Greer, who was tall, handsome, funny and gracious. This is notable for two reasons. First, Greer won the 2018 Pulitzer for “Less,” his comic novel about a hapless author named Arthur Less who has all of Greer’s worst characteristics — and none of his best. And second, “Less” covers all the joys and discontents of travel, and so does Greer’s new follow-up novel, “Less Is Lost.”

Greer is no overnight success. His first novel, “The Path of Minor Planets,” garnered strong reviews when it was released in 2001, as did “The Confessions of Max Tivoli” (2004, inspired by Bob Dylan’s “My Back Pages”). But his real breakout — before the Pulitzer — was “The Story of a Marriage,” about a woman who receives a fateful visit from her husband’s wartime friend.

With “Less,” however, came genuine fame, the kind that alters lives forever. And schedules. “I learned that after you win one of these big awards, you need a year for all the events and engagements,” says Greer, speaking over videoconference from his San Francisco apartment. (He splits his time between California and Milan, where his partner, Enrico, lives with their dog, Quo.)

“Less Is Lost” is more of a companion to “Less” than a sequel. Yes, Arthur Less has once again embarked on a journey, and yes, it involves the space operetta-creating author H.H.H. Mandern, a superbly satiric construction. But this time, our hero has fallen in love, and his journey’s purpose will be to accept that he is worthy of that love.

Like a great cross-country trip, our conversation — which is edited for length and clarity — meandered but stayed true to a general theme: how travel can open us up to the wonders, fears, divisions and many layers of the United States of America.

The latest from Ling Ma, Yiyun Li, Russell Banks and Namwali Serpell as well as exciting newcomers round out our critics’ most anticipated fall books.

Where did “Less Is Lost” come from for you?

Where comedy comes from. It’s from really, really dark places. When you hit the bottom, you’re like, OK, I have to go through this. I can’t stay in it anymore. I have to find another viewpoint. So, “Less Is Lost” started from the election of 2016. When Trump won, I thought, “I don’t understand this country at all. So I’m going to rent a van and go for six weeks to the Southwest and the deep South and just see what I see.”

You actually did this.

Yes. Arthur Less only goes for like a week and a half but I went for six weeks. No big cities. All small towns. I had to sit at the counter of the bar and talk to people. I didn’t have a pug named Dolly with me and I didn’t have just one van like Arthur does. I had three different vans.

What did you find out about America?

I made this trip in 2018, which feels like a world away from where we are now. I did get that everyone was in pain, from the policeman who stopped me for gliding through a stop sign to the owner at a taco place. The policeman wanted to be in the Marines, but he got a girl pregnant and so he had to join the police force. The taco-place owner had her dreams come true when the owner died and left her the restaurant. There was the lesbian couple running a sandwich shop in rural Alabama, a place they felt uncomfortable in but they had moved back there because one woman’s mother got sick.

It took just a minute for people to tell me the story that was right in their heart. It was so shocking. They were dying to say this thing that was causing them pain. I didn’t put their stories in the book. It’s not a book of pain. But it is a book of some empathy. That’s the mode of Arthur Less. He never makes fun of the place he’s traveling to but the joke is always on him, because he’s the thing out of place. That was my rule for this book.

So this isn’t a political book.

I’m not good at polemic of any kind. I have political ideas but I’m just not good at getting them across in fiction. So I’ve learned to stick with what I’m good at, which is humor and detail and a slight push toward talking about racial injustice. I didn’t want it to be a book about meeting Black people and seeing the light. I wanted Less to meet white people and talk about whiteness, to investigate that. I think that’s my job.

The Confessions of Max Tivoli: A Novel; Andrew Sean Greer; Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 274 pp., $23

Your narrator, Less’ partner Freddy Pelu, is a person of color. Why do we need Freddy as our guiding voice?

Because it’s a good way for me to have distance from a character who’s very much like me. To be able to make fun of Less in a loving way and in that sense to make fun of myself, because if I were writing a character like me in the first person, I would be much harder on myself. And it would be an unpleasant book, veering between pity and self-harm, and it would just not be joyous. Also, the Freddy voice gives me an omniscient narrator, and when you’re a writer that gives you everything.

Did you, like Freddy, head to the easternmost inhabited island in the U.S.?

I spent three months of the early pandemic trapped in Maine, delightfully trapped I should say, with the Chabons [Michael and his wife, writer Ayelet Waldman], who were generous enough to put me up. They went away for a weekend and I was like, “I’m going to go to the easternmost inhabited place in America, that might be something for the book.” I did go, but to Matinicus Isle. And when I reached the harbor, the owner’s caretaker called and said he was too old and ill to take in a visitor.

But you did take a train ride across the country. How did that affect “Less Is Lost”?

I took one train from San Francisco to Chicago, with my mother. Going through the Rocky Mountains on a train is like a Disney ride of beauty. Then I went from Chicago to Harpers Ferry, Va., and met up with my father. It sounds pretentious to say, but I wanted to write a book about America that was also a book about my country, the one I live in, not some idealized version.

But the joy in the travel is palpable. How does it connect to the larger themes in the book?

I was reading a lot of books about the gay experience as suffering and I thought, “This is not my experience.” In fact, my experience is that despite living through the AIDS years and despite terrible grief and oppression, the fight back has always been a sort of defiant joy. I haven’t seen that portrayed and I wanted my characters to have an ecstatic experience, with all the little details and funny moments that make you feel alive. I think that’s what makes travel a joy, that everything feels new. It’s very hard for me, but I try to remain present and notice what is beautiful and luscious right here in the moment.

Grant Ginder has made an art out of dysfunctional comedy that goes to dark places. He talks about the roots of his latest, ‘Let’s Not Do That Again.’

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.