How a ‘Call Me Kat’ actor decided he wanted to be more than ‘Brown Enough’

- Share via

On the Shelf

Brown Enough: True Stories About Love, Violence, the Student Loan Crisis, Hollywood, Race, Familia, and Making It in America

By Christopher Rivas

Row House: 240 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Christopher Rivas is an actor, playwright, podcaster, PhD candidate and now an author. But he knows people often see him — and judge him — first as a Latino. Rivas is both proud of his heritage and frustrated at being defined by it in a country where white people hold the power and the conversations about race tend to be about Black and white.

Rivas’ book takes on all that and more, as the subtitle spells out: “Brown Enough: True Stories About Love, Violence, the Student Loan Crisis, Hollywood, Race, Familia, and Making it in America.”

“My writing style is one of ‘Go,’” says the Los Angeles-based Rivas, explaining the jam-packed title and the essays within.

The book explores his self-doubt, his body dysmorphia and his anger at a system that consistently makes life harder for people of color. A regular on the series “Call Me Kat,” Rivas is open about the nose job he had before landing that role because a white manager told him it would improve his chances of being cast.

Rivas examines representation in Hollywood but goes beyond the usual talking points, just as he does in his other work. He has written a one-man show about Porfirio Rubirosa, a Dominican playboy and assassin, who some say was the inspiration for James Bond — typical, Rivas says, of how everything gets redirected and refracted through a white gaze. He has since created a podcast on the subject and hopes to create a feature film on Rubirosa.

The ‘Dirty Dancing’ star discusses the upcoming sequel, her memoir and the Supreme Court’s ‘fundamentally wrong’ abortion ruling.

Although he is part Dominican and part Colombian, Rivas grew up in New York and only recently began learning Spanish. In the book, he calls the American Dream a “pyramid scheme.” In a recent video interview, he declared, “America can feel like an onslaught for some people.” In “Brown Enough,” he charts his path to finding his voice as a writer, an actor and an American, a journey he hopes can help readers navigate their own way.

Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You write about the importance for you of seeing John Leguizamo onstage; you talk about casting an anti-invisibility spell. How much does genuine representation matter?

The whole book is about being seen. It often unfortunately means just movies and TV, but the art world is primarily white and the decision makers in most worlds, the check signers, are white. I want to receive fat checks, but things won’t change until the check signers look different.

You also explore the racism and colorism in the countries your family came from. How important is understanding your past to how you deal with daily life here?

Knowing my entire history is crucial. It’s important to know what systemic issues we’re attached to. It’s beneficial for us to take radical responsibility, to know why your grandmother felt this way about certain things or your mother said that to you. It helps you understand why you’re doing the things you’re doing, why all these women are straightening their hair, for instance. This precedes you; all the trauma is braided into you. There’s a lot of unbraiding you have to do.

Did writing the book help you shake the need for the white gaze? Or does being an actor mean that’s never going away?

I may always be dealing with it in Hollywood, but I now feel I’m able to stand up or speak up more. I’m more conscious of what I’m participating in and how I’m changing myself subtly to fulfill someone else’s needs. I feel more secure in myself, my voice and my space, and I know it’s expanding.

A Times analysis has found that Latino representation in film and TV has stagnated for a decade-plus, even as Latinos’ share of the population has grown.

In the book, you use that voice to confront individuals, like a photographer who calls a Latina he doesn’t know “spicy.” Is that exhausting?

Sometimes I can’t help it. It’s just in my nature. I’ve written about things that will get not nice responses and I’d love to debate every one of these people. But I do agree about saving energy. It’s about finding a balance.

I was just at a photo shoot and the hair and makeup person was a wonderful white woman. We started talking about photography, she said, “We have a photography group in L.A. You should join. There’s a couple of Spanish people in it.” She kept saying that, but I didn’t need to do anything. She was really genuine — she was also trying to learn Spanish. That’s the difference with microaggressions. Sometimes when you’re asked, “Where are you from,” the person is just trying to connect.

People of color are incredible mathematicians. We have to solve problems in an instant: Who is this, what situation am I in, am I going to make things uncomfortable, is it worth it? We are doing crazy algebra and that can be energy-wasting. But the little things matter. If you’re moved to say something, it might be worth it, because little things add up.

Will writing this book and finding your voice make you a better actor?

My first response is, “Wait, I’m already a pretty good actor.” [Laughs.]

Maybe I can do more on my own, but there is something that must be given from the writers room. I was on a TV show and there was no one brown. There were two Black people and nine white people. It doesn’t match. I want richness of language in characters, which is what you often don’t see in nonwhite characters — they’re not as specific and quirky.

It’s something Hollywood can get away with — give an occasional speaking role to people of color and say, “We did it.” But it’s about who’s writing those roles and telling those stories. So, more and more I want to be the one behind the scenes. The change I want won’t happen until I can hire someone and give them an opportunity.

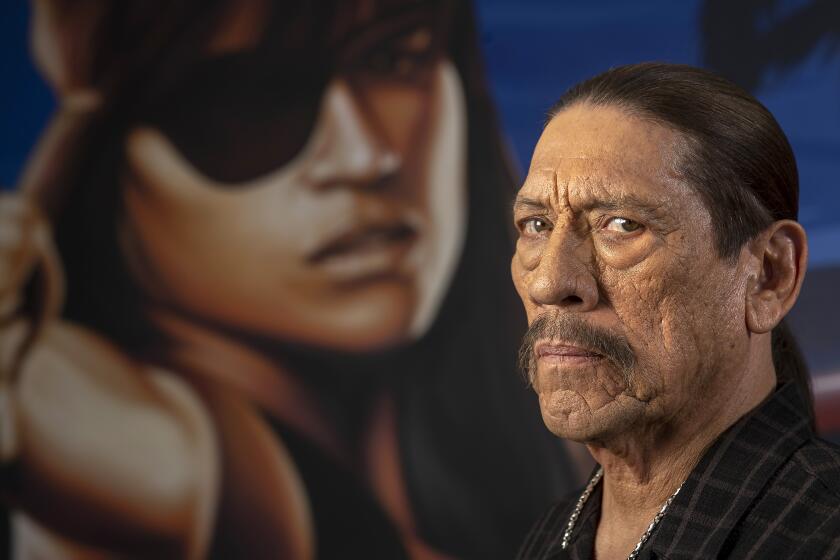

‘Acting wasn’t new to me. I’d acted to survive my childhood,’ writes Danny Trejo in his new memoir. He talks with The Times about his incredible life.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.