The book world needs practical dreamers. Enter publisher-novelist Martin Riker

- Share via

On the Shelf

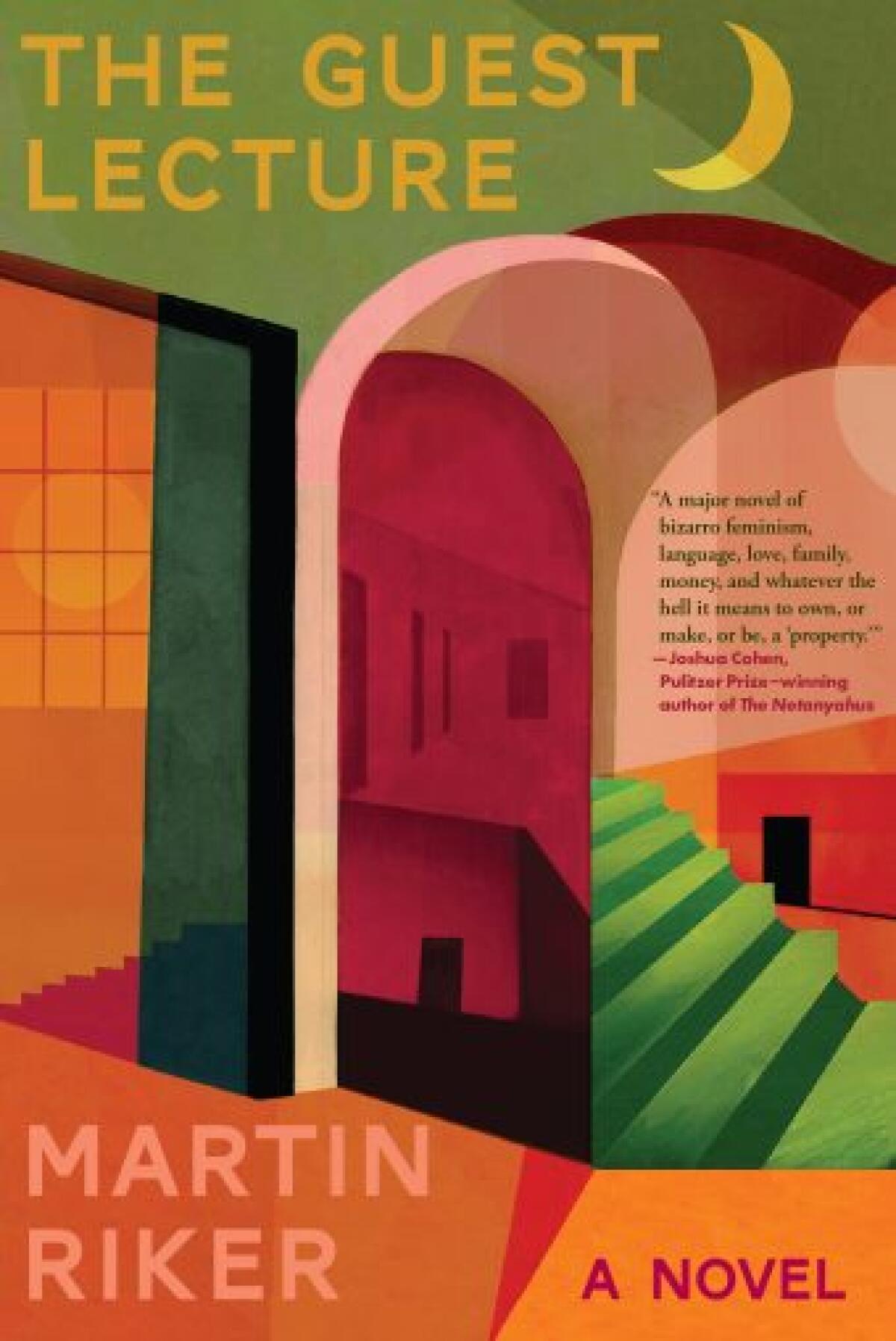

The Guest Lecture

By Martin Riker

Grove: 256 pages, $17

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

It’s difficult to talk with Martin Riker and not feel hopeful. Not so much about the world; both of us are likely too old to presume to know what might come of society, the planet, human beings. But talking with him, and reading his new book, “The Guest Lecture,” lit me up in thrilling ways about all the possibilities still alive — at least for books.

Then again, books and life, ideas and the concrete, the imaginative and the practical, are not opposites for Riker or for his protagonist, Abby. “There’s a William Carlos Williams quote,” says Riker, speaking from his home in St. Louis, where he teaches writing at Washington University. “Something to the effect of, ‘Only the imagination can save us’. … As a young man, I wanted to tattoo it on my arm. But I decided that it needs to mean something practical. It can’t mean something just idealistic.”

Riker has been walking that line for some time; few projects combine the imaginative and the practical as well as Dorothy, the micro-publishing house he runs with his wife, novelist Danielle Dutton. His first novel, “Samuel Johnson’s Eternal Return,” had a narrator whose consciousness moved helplessly among bodies as he searched for his lost son — imagine an existentialist “Quantum Leap.” But it’s in “The Guest Lecture,” his second novel, that the dialectic between fantasy and figures, consciousness and bodies, takes its most affecting form.

Abby is an economist, because in college a boy made fun of her for not being practical. But she is also an academic, because her affinity for the practical went only so far. Also a wife and mother (practical or idealistic?), she’s recently been denied tenure. And she has been invited to an unnamed institution to give a lecture on John Maynard Keynes. “He embodies someone who has huge ideas,” says Riker. “Really strange ideas, and actually was incredibly doggedly focused on making them practical.”

What if at the moment of your death, your consciousness was transported to another body, a body through which you can see and hear but not taste or smell or feel?

Abby is feeling anxious, insomniac and unprepared. Her husband, Ed, has suggested to her that the best talks are the ones where the speaker “wings it.” She finds this idea terrifying. But then Ed, both deeply charming and often ineffectual, has more advice. He suggests she use the loci method to remember her speech.

The method’s origins are gruesome. Simonides of Ceos, “a poet who lived so long ago that he actually invented several Greek letters,” felicitously avoided a roof collapse at a fancy party (“maybe he needed to pee”). As the sole survivor, he needed to identify the dead. So Simonides imagined himself moving through the rooms to name everyone he’d seen.

Abby therefore spends the night imagining her way through the various rooms of her own life, attempting to attach each beat of her speech to a recollected physical space. This dreamscape becomes Riker’s plot, as Abby not only visits memories but also consults with various thinkers. Keynes functions as both guide and heckler as she attempts to move through her speech.

Riker knows well the old adage of writing instruction: “Dreams have no stakes.” He checked in with Dutton, asking: “Do you think I can just end this thing in a dream?” She laughed and said, “Go ahead!”

It makes an organic kind of sense here. Abby spends the whole night battling perhaps her greatest foe: her own brain. She has just lost tenure; Trump has been elected. One can’t help but think throughout the novel of all those people crushed beneath the roof in the story of Simonides. But then the book is also ebullient, lively, often very funny; Abby describes what’s most important to her in writing as “the life inside the language,” and this whole book is so gleefully, wondrously full of that life.

“What I actually think is Abby’s most remarkable trait,” says Riker, “is that she has a very creative, imaginative mind, and it’s almost not something she’s even aware of, the degree to which she’s able to remake the chaos, remake the badness, and turn it into something that has liveliness.”

For generations, intelligent literary women have been drawn to Virginia Woolf for her complex, independent-minded works such as “A Room of One’s Own.”

One quote I thought of while we were talking is from Edgar, the falsely accused and only legitimate son of Gloucester in “King Lear”: “the worst is not/ So long as we can say ‘This is the worst.’” So long as we have language, a form through which to articulate our despair, to give the chaos shape, the worst is not yet here.

“One of the ways we think about playfulness with form is it’s a way of dealing with the inarticulateness of experience,” Riker says, “and the point of the playfulness is that you aren’t just putting experience into the premade boxes that the literature has already put them into. ... that’s the difference between form and formula.”

Although Riker has little interest in the formulaic or didactic, he considers literature a conversation above all else; he works in models, talks through other books. “Let me go to some other books,” he says more than once during our conversation, which left me with a full-page list of books to read.

Riker came to writing through music and then independent publishing. Riker was a trombonist (and temp worker) in Manhattan, worked for Dalkey Archive Press in Illinois and met Dutton in Chicago. After a sojourn in Denver, where they both earned PhDs in English, the couple decided to start what Riker calls “the most important thing I do”: Dorothy, a Publishing Project, a self-deemed feminist press that puts out two books a year.

It was Dutton’s idea to build a space explicitly for female writers. Riker is very firm about her initiating it, though he feels “pretty sure the word ‘project’ was my idea.” They have run it together from their home since 2009.

“One of the things I’m most proud of about Dorothy,” Riker says, “is that it puts something into the world that has an ethical vision of what literature is and how it can be published in a way that maintains the ethics of conversation, but also it’s practical and we make practical decisions.” The publishing schedule is a perfect example: Two books annually are all they can handle with care, but the pair is published simultaneously, meant to be in conversation with each other.

‘Avalon,’ the latest novel by Nell Zink, follows an odd girl named Bran through an untenable love affair and all manner of absurd indignities.

Dorothy has consistently put out excitingly fresh voices (not unlike Abby’s): Sabrina Orah Mark, Nell Zink, Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, Renee Gladman, Amina Cain. They very recently started a partnership with New York Review Books that will expand their reach. What unites Riker’s ventures in publishing and writing is “that balance,” he says, between experiment and impact: “Thinking always about the forms and structures of the world, but not thinking about them just to blow them up. Thinking about: How can they be different, and how can that practically mean something in the world?”

Abby says, late in the book: “Uncertainty is a fact of life and an important part of what makes life lively. … Risk is the spirit of courage you bring to the things you care about.”

If all books are models for those yet to be written, a drop of something into the larger conversation that might spur us on, there’s something courage-giving about the fact that Riker is such an active member in that conversation and that “The Guest Lecture” is here to give the chaos its own specific form.

Strong is a critic and the author, most recently, of the novel “Want.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.