Reviving a novelist of monsters and men: Why Rachel Ingalls matters now

- Share via

On the Shelf

Rachel Ingalls Novels, Reissued

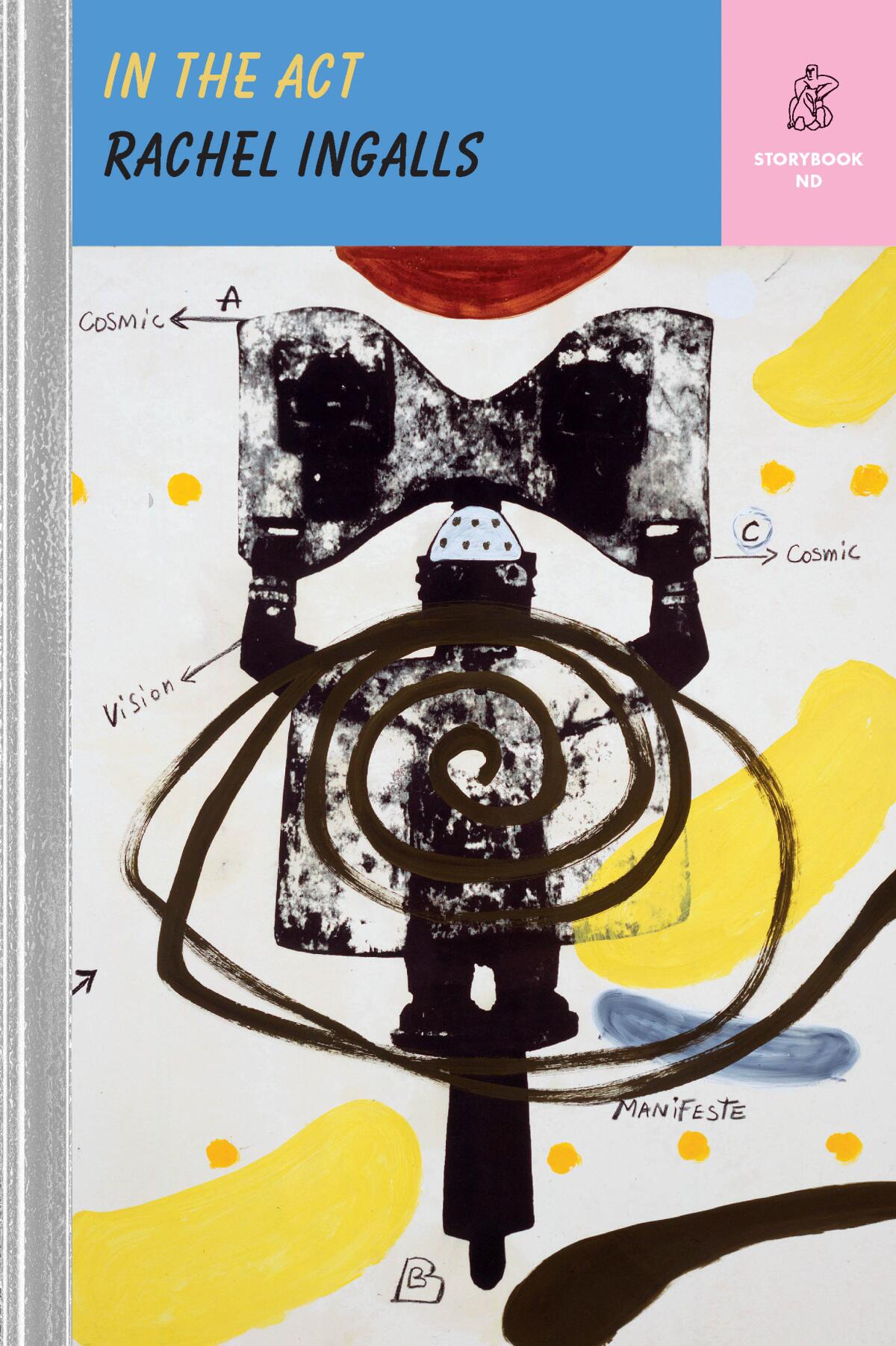

In the Act

New Directions: 64 pages, $19

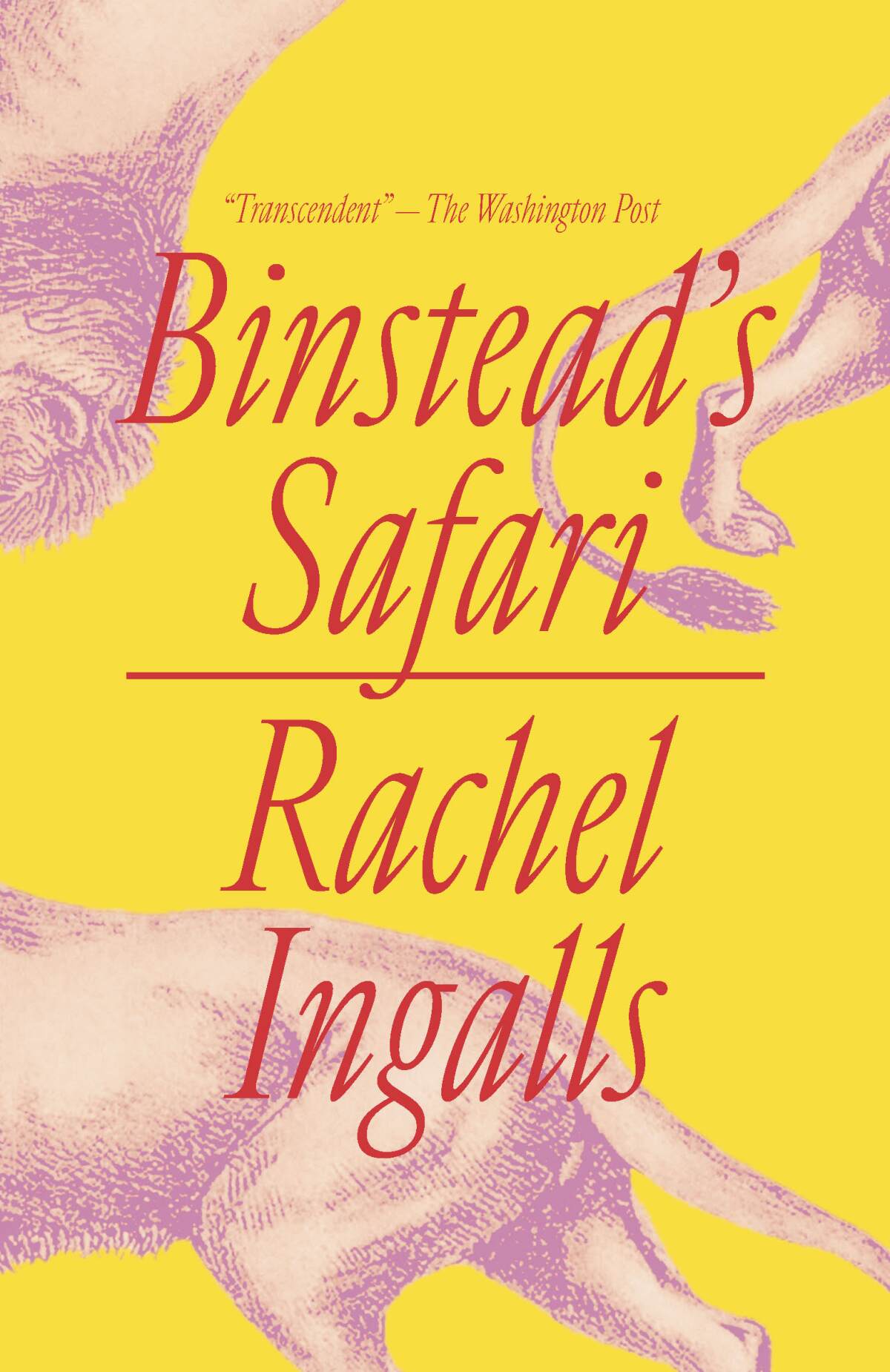

Binstead’s Safari

New Directions: 224 pages, $16

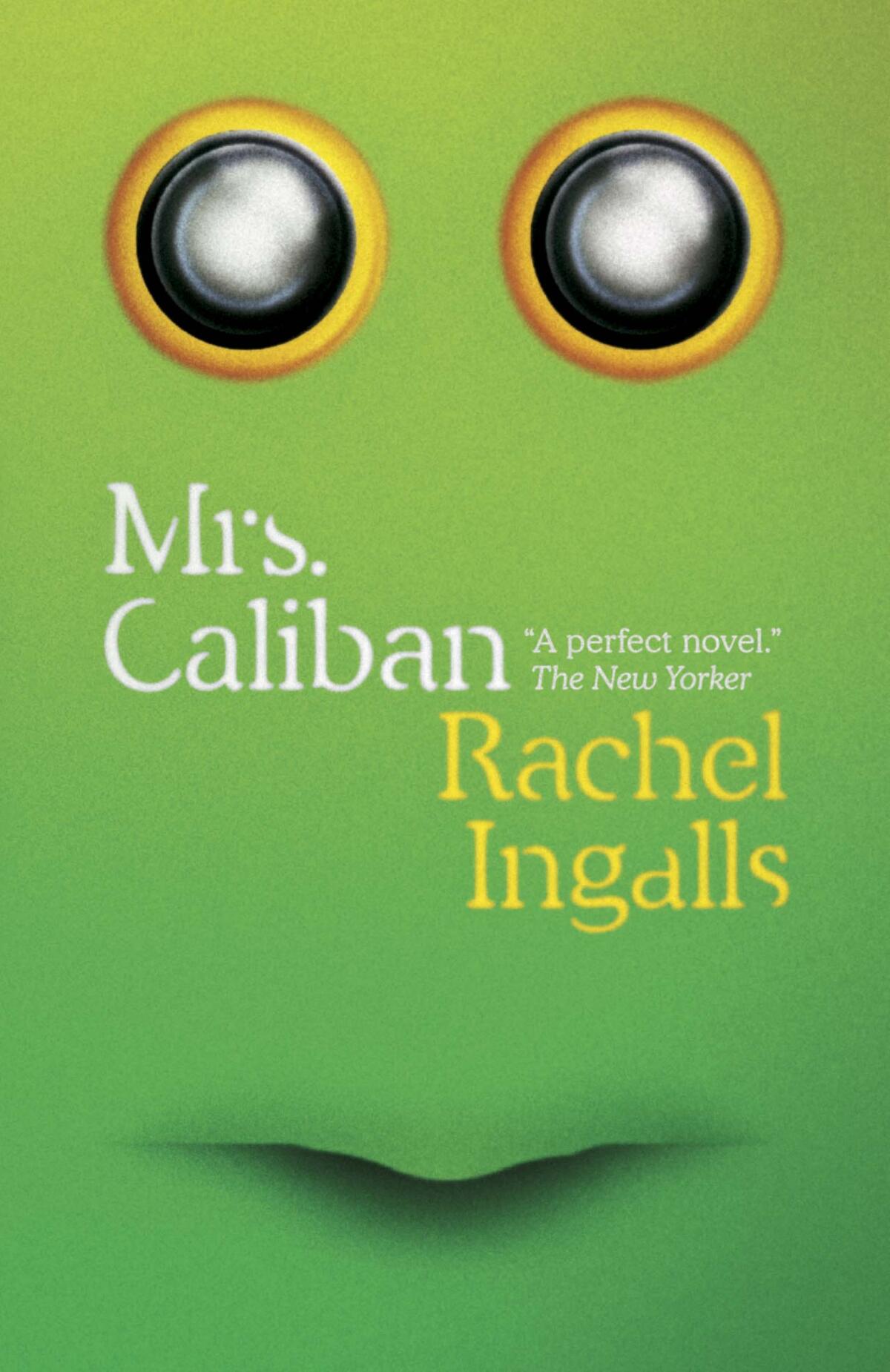

Mrs. Caliban

New Direction: 128 pages, $14

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In March 2019, New Directions reissued Rachel Ingalls’ out-of-print 1983 novel “Binstead’s Safari.” A New Yorker profile was published in the March 4 issue to coincide with its publication. Just two days later, Ingalls died, at 78, of multiple myeloma. Her friend, writer and painter Hugh Fleetwood, told the New York Times that the recognition that came in her last days made her extremely happy. “Not merely happy,” he said, “but — like Violetta in the final scene of her favorite opera, ‘La Traviata’ — reborn.”

Nonetheless, Ingalls remains largely unknown. So rarely was she profiled that the obituaries and appreciations tend to recycle the same quotes from a rare interview she gave to the Boston Globe in 1987. “Mrs. Caliban,” Ingalls’ 1982 novella, came back into prominence when New Directions smartly reissued it in 2017. The book’s merits were many, but it didn’t hurt that its plot parallels “The Shape of Water,” Guillermo del Toro’s Oscar-winning film of the same year. The similarities were so uncanny that allegations of plagiarism were floated. (Del Toro said he had never heard of the book.) A year later, the publication of Melissa Broder’s “The Pisces” prompted the New Yorker to declare “the completion of an unofficial pop-culture trilogy of human-meets-fish love stories.”

“Mrs. Caliban” by Rachel Ingalls is an unusual book with an unusual publication history.

But enough of recycled anecdotes; there are plenty of fresh discoveries to be made among Ingalls’ work. In addition to “Caliban” and “Safari,” this month New Directions rereleased her 1987 short novel, “In the Act,” as part of its Storybook series.

“In the Act” is a perfect fit for the series, which is meant to “deliver the pleasure one felt as a child reading a marvelous book from cover to cover in the afternoon.” This one is definitely not for juveniles. Helen’s husband has been holed up in the attic, working on his “experiment.” As long as Helen’s out of the house and out of his hair, everything’s peachy. But when Helen’s adult education classes get canceled, she hops up the attic steps to discover what her husband’s been working on.

Sylvia Plath’s 1963 poem “The Applicant” asks of a robotic wife, who brings “teacups and rolls away headaches / and do whatever you tell it / will you marry it? ... A living doll, everywhere you look. It can sew, it can cook. / It can talk, talk, talk.” Who knows if Ingalls read Plath, but she was born in 1940, meaning she would have been 25 when Plath’s “Ariel” was published, prime time for a young woman with literary aspirations — who traveled to England, like Plath, and never left — to read and appreciate her work.

Much of Ingalls’ fiction deals with the depressive realities of marriage and the frightening disregard, ambivalence or pure hatred husbands have for wives. “In the Act” is a funny story, well in line with the rest of the author’s vision. But Ingalls’ big book is “Binstead’s Safari,” in which Millie is tagging along on husband Stan Binstead’s trip to Africa, where he’s doing anthropological research on religious cults. Stan hates that she’s with him: “I should have said: take a vacation wherever you want to, as long as it’s a long way away from me.”

Why did Penguin decide to reissue a memoir and a novel by Harry Crews, a dead white Southern writer? His influence — and his truths — run deep.

Stan is under the impression that Millie can’t have children. In fact, she’s been on birth control since they were married. Many of Ingalls’ heroines have experienced the loss of a pregnancy or a child or both. But Millie makes a choice not to become pregnant after a conversation with her sister, who is expecting her fourth child. “As far as she was concerned, they weren’t children; they were unwanted pregnancies, all of them,” her sister explains. “One day she would realize that her whole life had just been this: putting up with things she didn’t like, because they were forced upon her.”

The idea that the only real children of a human being are the children that they actively chose to have is a provocative idea, even in 2023, a year after the Supreme Court’s ruling against reproductive freedom.

As the Binsteads settle into their safari, it turns out Millie is in her element. She’s done extensive reading on the region, and the hunting guides are charmed by her. “Millie felt at peace. Strength had come back into her, and just as suddenly as this: the sun rose and everything was different. … Nothing threatened her. She had found her life.”

Millie, like Dorothy in “Mrs. Caliban,” finds herself through a mysterious and perhaps monstrous paramour. In Millie’s case, it’s Henry Lewis, a game tracker respected — even feared — by poachers and tribesmen alike. He is the only one who can tame the lions. For Dorothy, the lover is an aqua-man monster named Larry who finds her perfect even in her bathrobe, her hair unset. While Dorothy’s story ends sadly, “Binstead’s Safari” fulfills the promise of “Mrs. Caliban”; Millie’s end is complex and fascinating. Beginning like Ernest Hemingway’s short story “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (which is referenced in the novel), “Safari” expands into themes much weightier than masculinity under threat.

As exacting and detailed as Ari Aster is as a filmmaker, he’s surprisingly low-key about how to pronounce the title of his new film, “Midsommar.”

Part of the novel’s impact owes to its shifting point of view. At first, we’re with Millie most of the time, but gradually the book shifts almost entirely to Stan’s perspective. Obviously, there’s a feminist element to all of Ingalls’ work; for one, it presents monsters as preferable mates to human men. We want Stan to realize how he’s failed Millie. But in the end, knowing his thoughts and the way he reacts to the novel’s shocking climax, we know Stan still doesn’t get it … at all. This utter failure of emotional intelligence is the true monstrosity in Ingalls’ work.

The resonance of this theme in contemporary pop culture goes far beyond “The Shape of Water.” “In the Act” called to mind the themes in the television series “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” but the one film I couldn’t shake while reading Ingalls was Ari Aster’s “Midsommar,” described by some as the most terrifying movie ever made about a breakup. Dani’s boyfriend, Christian, fails her in many subtle but crushing ways, leading to the film’s intensely satisfying finale.

Ingalls knew something about the power of being seen. When Millie meets Henry in “Binstead’s Safari,” she can finally see herself (and the world) beyond Stan’s perception. And yet the self-actualization of Ingalls’ heroines isn’t quite independent; it still comes through a male vector. The utopia of that other world is undeniably attractive, but why is a woman’s only other alternative from a life of diverted desire the violence of a death cult? The answer is anger. And the release of that anger is more than entertaining; it’s erotic.

Like Dani at the end of “Midsommar,” Millie flies to that new world with open arms. For Stan, “She just stepped forward and embraced the horror; like going into a furnace, like throwing your arms around a bomb.”

Ferri is the owner of Womb House Books and the author, most recently, of “Silent Cities San Francisco.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.