Spiritual awakening via giant cactus: Only L.A. author Melissa Broder could pull it off

- Share via

Review

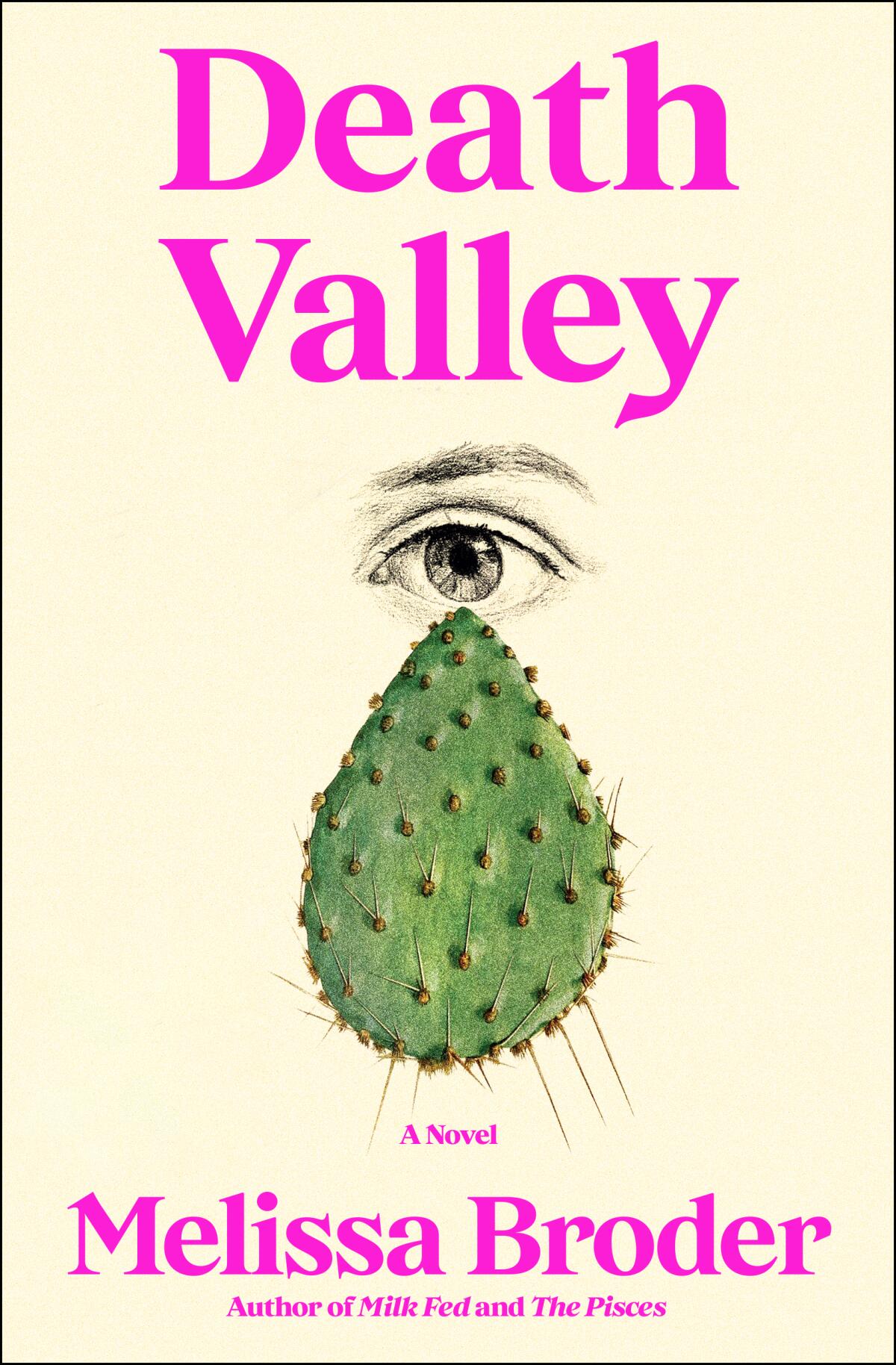

Death Valley

By Melissa Broder

Scribner: 240 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Melissa Broder’s 2021 novel, “Milk Fed,” featured a smorgasbord of life-affirming lesbian sex and body positivity, brought on by a golem in the form of an Orthodox Jewish woman whose family owns a frozen yogurt chain in Los Angeles. It was as wacky and wonderful as that sounds. In her latest novel, “Death Valley,” Broder turns to a grimmer topic — grief. But her disarming and whimsical style remains intact.

An unnamed woman travels to a Best Western in the middle of the desert outside Joshua Tree to escape her father’s second hospitalization in L.A. She’s also escaping her husband, who suffers from a debilitating illness, and whom she loves, though she wonders, “How can I want my husband when he’s always right there?” Listening to an audiobook on grief, she balks: “Who unravels this neatly? ... I’ve been more unraveled by a yeast infection.” Broder, who lives in Los Angeles, has written about her husband’s illness, and “Death Valley” is dedicated to her father.

The poet, viral tweeter and author has a new novel, “Milk Fed,” imagining an explicit affair between a damaged Hollywood loner and a plus-size woman.

The book’s protagonist is trying to finish her novel about a woman with a similarly ailing husband. “To write and doubt that you will fall asleep, or keep falling asleep, before you finish the thing, and then have life (or god, or something) jostle you awake and resolve the doubt and provide a path forward — this is why I write,” she writes. “I do it for the alchemy. I cannot just experience things. This is how I experience things.”

Out on a hike near the hotel, she discovers a giant cactus and slips right in. Inside, she dreams — or sees — a little boy. “Then I recognize the child. The child is my father.” Back at the hotel, she feels like she’s had a spiritual experience. “Does having visions inside a cactus count as a relapse? No, it’s a sober phenomenon. A gift.”

Broder’s own gift is for scenes and dialogue that are so natural — in that they reflect the ridiculousness and surrealism of real life — that they tip over into the uncanny. She is also very funny. “Dr. Mahjoub was a woman who ate when she was hungry and stopped when she was full,” she writes in “Milk Fed.” “She was probably someone who genuinely enjoyed a nice pear.” And she can turn a sentence: “I knew how she made me feel, which was full of confetti instead of blood.”

She also knows how to start and end a chapter and — most important — a novel. Like “Milk Fed,” “Death Valley” is never, ever boring. This is high praise considering that our heroine spends 85% of the book in the desert and the rest at a Best Western.

“I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness” is a novel torn from Watkins’ desert life — Charles Manson, addiction and the incessant pursuit of true freedom.

There were moments in this book that called to mind Sheila Heti’s most recent novel, “Pure Colour,” in which the heroine’s father dies and becomes a leaf. It also reminded me of Patricia Lockwood’s novel about loss, “No One Is Talking About This,” which is hilarious until it’s horrifyingly sad. In “Death Valley,” the woman looks up in the desert, hopelessly lost: “My mother is under this sky. My sister and baby are under this sky. My father is under this sky. My husband is under this sky. Still, such a big aloneness.”

Because the woman is alone, her time in the desert is spent interacting with herself, her memories and the occasional rock, bunny or, as she calls it, a lizard-iguana. “I won’t ask how you’re doing,” she tells the lizard-iguana. “Or project anything on you.” Because her journey is solitary, “Death Valley” lacks the interpersonal richness and sensuality of “Milk Fed.” Broder is after something different here, but there’s an emotional distance between the reader and this unnamed woman. Leaving readers wanting more, though, is not necessarily a bad thing.

Determined to hike up a mountain and perhaps relocate the cactus, the woman tries to scale a penis-shaped rock. And she falls. “I fall for what feels like days. ... I am humbled by the sight of my own blood.” What began as a book about the narrator grappling with the death of others has now become a book about her own survival. “I picture a grave in the middle of this barren terrain — a pixelated grave like the old ‘Oregon Trail’ computer game...

HERE LIES ME

WRITER.”

Tod Goldberg’s ‘Gangsters Don’t Die’ concludes the series of ‘desert noir’ featuring a fake rabbi — and the very real spiritual journey that led him there.

“Death Valley” is about death, and also how to live with it. “How do you practice for dying?” she wonders in the middle of the desert. “It’s brave of us to die! ... How tenderly I feel for all of us when I think of this. ... Graveside, we stood there like winners. And the one in the ground had lost. But the win was temporary, and time was speeding up. Everybody into the ground. Everybody already in the ground.”

For writers, the fear of death is also a fear of failure; a fear of not being able to get it done. “Death Valley” reminds us that grieving and writing are much alike. “Sometimes you say I’m going to kill myself,” Marguerite Duras wrote in “Practicalities.” “And then you go on with the book.”

Ferri is the owner of Womb House Books and the author, most recently, of “Silent Cities San Francisco.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.