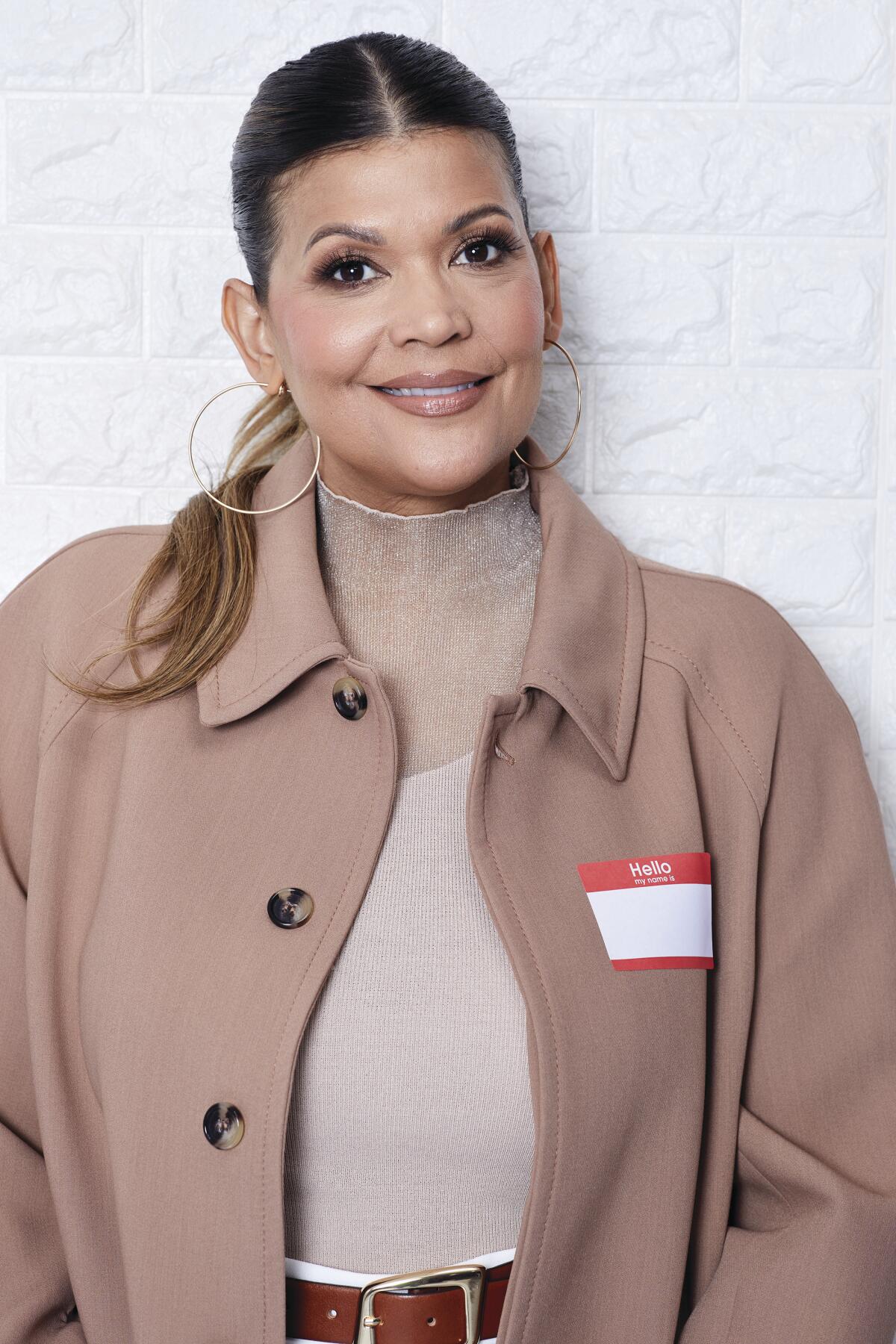

Latina comedian Aida Rodriguez tackles the shame of ‘illegitimacy’ in a new memoir

- Share via

On the Shelf

Legitimate Kid: A Memoir

By Aida Rodriguez

HarperOne: 256 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Aida Rodriguez was raised by women who could take down the devil.

Her abuelita carried a .38 Special pistol. Her mother beat up her daughter’s bullies with chanclas (a.k.a., the always-effective flip-flop) and threatened them with other makeshift weapons. It’s no surprise that the L.A.-based American comedian made a career of going for the oppressor’s jugular — in her case, with words.

Her stand-up mocks the myths of white supremacy and other human hierarchies. “If we don’t get our s— together, when the aliens come, they’re gonna f— all of us up,” she warns in her HBO special “Fighting Words.” On doomsday, white racists will be desperate for Black and Latino friends, she predicts, “‘cause they can’t fight like us.”

Rodriguez, of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent, brings heart and humor to universal issues such as race, motherhood and survival, often through the lens of Latinx experiences. “We come from Supreme Court justices and crack dealers and everything in between,” she said in a recent phone interview. “And every single person is a human being on that spectrum, and they are all worthy of their story.”

After Aida Rodriguez moved to L.A, she lost her car, her home and her hope. Everything would change after she did stand-up at a friend’s birthday roast.

In her heartbreaking new memoir, “Legitimate Kid,” Rodriguez documents her journey to self-acceptance as the daughter of an absent father. Amplifying her internal sense of impostor syndrome was the more insidious social stigma she faced — a sense of illegitimacy that countless people feel because they were raised by single, unwed moms in an American culture that adulates the patriarch and racializes single parenthood.

As I was reading the book, I remembered the illegitimacy I felt as a child when I realized my parents were unwed. Rodriguez’s story helped me reframe my own lingering insecurities. I met Rodriguez in 2018, when she was performing at a California Chicano News Media Assn. event at which I was receiving a journalism award. Her words struck a chord. I’ve followed her work ever since and was eager to talk with her about her book. We spoke over the phone in a conversation edited for length and clarity.

As you know, I grew up with an absent father and wrote my own book about it. There’s a lot of shame when it comes to fatherlessness that I think we don’t talk enough about. What do you hope readers learn about illegitimacy?

I’ve always felt so alone in it. I really hope that everyone who reads that book allows it to be their own certificate of legitimacy. People that are told they are not enough, or they’re undocumented or speak with an accent or didn’t grow up here. I really want people to find a sense of legitimacy from within and understand that [it] is a concept that comes from patriarchal white supremacy roots. It has been weaponized so greatly against our people. It’s so toxic, it’s so harmful.

You also delve into your experiences of colorism and anti-Blackness, a theme in your stand-up as well. For example, you recall how your white Cuban stepfather called your Black grandmother “ordinaria” because of her darker features and also used racist language against you. How were you able to hold onto your sense of self-love and beauty?

A lot of times I did feel dirty. But even though my stepfather said, “You are less than,” my grandmother was there to whisper in my ear, “No, you’re not, you are more than enough, you are everything.”

Comic Aparna Nancherla, who spins insecurity into gold, explains how her new memoir, ‘Unreliable Narrator,’ unpacks impostor syndrome and counters go-go feminism.

You write that when your stepfather assaulted and left your mother for dead in [New York’s] Central Park, it was society’s perceived “undesirables” who saved her. Your mom told you: “Never look down on anyone. It was the prostitutes and junkies that rescued us.” How do you reflect on that lesson today as an artist?

I come from people who are looked down on. My grandmother was illiterate. She was an immigrant Black woman that came from Puerto Rico in the ’50s. My uncles had blue collar jobs … I’ve always had a certain level of respect for the people from my neighborhood where I grew up. I used to look at my grandmother with the emoji heart eyes. She was so dope, so funny, so smart. She was also very empathetic. We were really poor, and even still I’d see my grandmother fix a plate of food and take it to the guy sleeping on the street. If [my mother] had $2, she’d give them one of her two. I grew up around people who respected everybody, not just people who society deems of higher value. And it’s just who I am now.

You write with great affection about the loving but often troubled men who helped raise you — uncles who suffered from addiction and other problems. The type of men who are often reduced to criminals in the mainstream media. What do you hope to accomplish in telling their stories?

I wanted to humanize my uncles. It’s amazing how we can watch movies with white men who struggled with addiction, and their stories are victorious stories: Robert Downey Jr. turned his life around. Well, I have an uncle who’s been clean for 30 years, and he might not be Iron Man but he goes out into the community on a daily basis and works with people battling homelessness and addiction. To me, that’s a hero. I wanted people to know I come from great stock — I don’t care what anybody else classifies them as. I am everything I am because of those people.

You write that it was your children who helped you understand that you were a complete person. There’s a beautiful scene of your daughter, when she was in kindergarten, signing her last name as Rodriguez instead of her father’s last name. You were shocked. What do you think gave her the confidence to claim you at such an early age?

She came here like that. When she was born, the doctor who delivered her said, “This one’s gonna be a pistol.” ‘Cause my son was the peaceful warrior, [but] she had all the confidence in the world. And she knew Rodriguez was the name that had honor and respect.

Alejandra Campoverdi’s ‘First Gen’ tells a story at once unique and familiar — that of a first-generation American becoming first in the family to attend college.

Is there something other Americans can learn from Puerto Rican women?

There’s a strength and assertiveness that comes with Latinidad when it comes to women, ‘cause Latinas have to endure so much. Culturally, machismo is embedded into the fiber of who we are: The men are coddled, the sons are coddled, the daughters are indoctrinated into emotional physical labor. You have to take care of the family, you have to translate … And with all of that comes a level of muscle that gets strengthened throughout time, to be able to endure.

This country prides itself in being strong and tough. What is tough, now? Tough is talking smack on the internet, beating up and lying, bullying people that are defenseless, using power to abuse and oppress. That ain’t strength to me. Actually, that’s soft.

In this country where so many people claim to be patriotic, to be strong ‘cause they have guns and they’re a bunch of tough guys, they would never be able to endure the things my grandmother endured. I know it. Without a weapon? Without literacy? Without speaking the dominant language of the land? You wouldn’t survive a day. Maybe that’s why they hate us so much. Maybe it’s just envy.

Rodriguez will be discussing and signing her book on Saturday, Oct. 21, at 3 p.m. at Book Soup.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.