- Share via

Nigel Hudson was at the top of his career. A professional boxer, schooled in martial arts, he had carved out a successful niche in Hollywood training actors and rock stars, as well as choreographing fight sequences for films like “Mr. & Mrs. Smith,” when his life came crashing down in a devastating accident on Sunset Boulevard.

Hudson was driving to Malibu with two friends on the morning of Jan. 7, 2007. While he was stopped at a traffic light, a truck rear-ended his Lincoln Navigator.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Hudson, then 38, suffered a traumatic brain injury, a broken neck and numerous other physical injuries that would require multiple surgeries and medical treatments. After years of litigation over the accident, in 2011 he was awarded a $13,863,000 settlement. More than half of the money went to pay Hudson’s attorneys and his initial medical and other expenses. The remainder left him with a substantial financial cushion for his livelihood and future medical costs.

But then Hudson’s ordeal began.

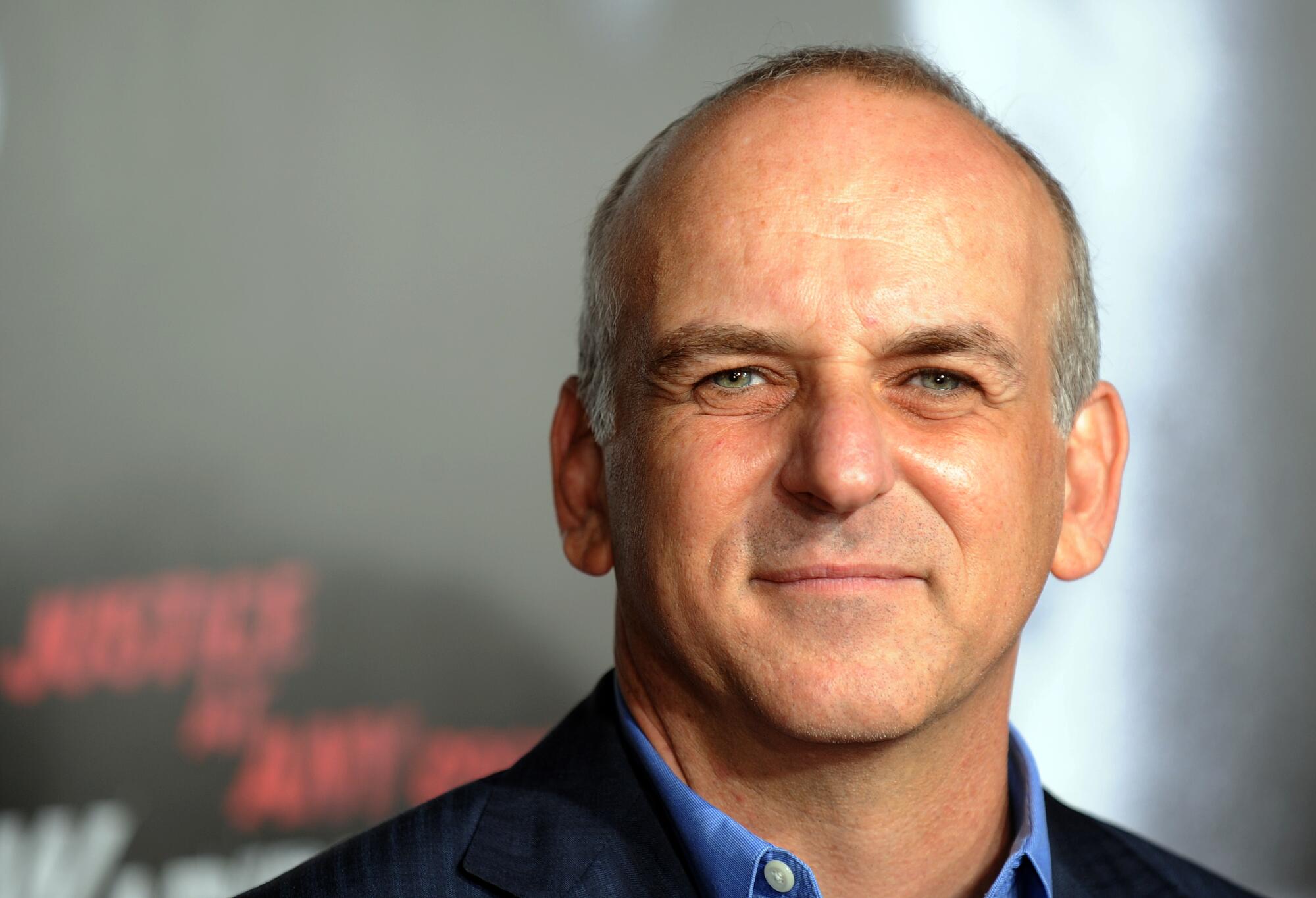

In the spring of 2012, Hudson agreed to have his longtime friend, Lucas Foster, appointed general conservator over his estate. The legal arrangement gave Foster, a movie producer with a lengthy résumé of credits including the films “Ford v Ferrari” and “Bad Boys,” broad control over Hudson’s finances.

In court filings, Hudson alleged that Foster, whom he considered his “brother,” took advantage of his position and stole money from the conservatorship, writing checks to himself and his various film companies as “reimbursement” for expenses that he didn’t pay.

“I wanted my life back”

— Nigel Hudson

Foster declined requests to be interviewed. In a statement, his publicist, Howard Bragman, said: “This is a classic tale of letting no good deed go unpunished. ... It’s clear that Lucas Foster acted honorably and in his former friend’s best interests at all times. Mr. Foster and his team are confident that the claims, made by Mr. Hudson in the court of law, will continue to be resolved in Mr. Foster’s favor, which is where he will be making his case, vs. in the media.”

Foster’s handling of Hudson’s money eventually erupted into a long legal battle, one that highlights the immense power conservators wield and raises questions about the potential for abuse in a legal system that was set up to protect against exploitation, legal experts say.

Hudson contends that he only discovered the alleged fraud four years after the conservatorship ended in 2014, long after a Los Angeles probate judge and the court-appointed guardian ad litem signed off on Foster’s final accounting.

“I trusted him,” Hudson said. “To steal from someone who’s recovering from a brain injury ... you’re the one in charge of all their finances and you’re pilfering under their nose — that’s disgusting.”

In early September, the California 2nd District Court of Appeal faulted a lower court’s ruling that denied Hudson’s motion to set aside the court’s approval of Foster’s financial accounting of the conservatorship.

The appeals court determined that the probate court erred in placing too high a burden on Hudson to determine fraud.

Michael Augustine, Foster’s attorney, declined to comment for this story.

“Mr. Hudson and his counsel have made a lot of baseless accusations and are attempting now to use the press to serve their interests. Since there is ongoing litigation, Mr. Foster will address the allegations in court, not in the press, and is confident all claims shall be resolved in his favor,” said Alan S. Gutman, a lawyer who represented Foster in a separate civil action, in a statement to The Times.

An L.A. judge ruled Friday to terminate Britney Spears’ controversial conservatorship. These stories explain the long and complicated history behind it.

In recent months, Britney Spears’ vituperative legal battle to end her controversial 13-year conservatorship and wrest control of her life and finances from her father has put conservatorships under the spotlight and prompted calls for legislative reform. While such a high-profile conservatorship is headline-grabbing, countless others rarely merit much public scrutiny.

Back in 2005, a Times investigation into the conservatorship system reported on widespread abuses, finding that “oversight is erratic and superficial” and “judges rarely take action against conservators.” A year later, the California State Legislature passed an extensive overhaul of the system, but many of the reforms weren’t funded after the 2008 recession.

Adam Streisand, a lawyer whom Spears tried to retain in 2008 early in her conservatorship, described the probate courts that oversee conservatorships as overworked and underfunded.

“Sadly, the reason why we have conservatorships is because there are people who are vulnerable to manipulation and being taken advantage of,” he said. “It’s hard to protect vulnerable people from the people who are supposed to be protecting them.”

Hudson was 26 when he arrived in Los Angeles, a trained boxer from Taunton, England, which is known for its 10th century monastery. Broke and not knowing a soul, he landed at Wild Card Boxing in Santa Monica, where he said for a time he slept on the boxing ring. “It was the most comfortable place in the gym.”

It also opened the door into the entertainment industry for Hudson. He trained Orlando Bloom and Michael Peña for the 2004 film “The Calcium Kid.” A meeting with Arthur Fogel, Live Nation Entertainment‘s president of global touring, connected him to Madonna, whom he said he joined on tour in 2006 as a physical trainer.

At the gym, he met Foster and his wife, who was taking lessons there.

“We started off as clients, and then we became friends,” Hudson said.

According to Hudson, Foster arranged a meeting between him and Doug Liman, who was directing “Mr. & Mrs. Smith.” In addition to choreographing fight scenes, Hudson trained Brad Pitt for the 2005 film.

The accident put an end to all that. As court filings described, Hudson was left depressed, angry, easily distracted and isolated. He separated from his wife; they have since divorced. He was also in and out of medical care, including nearly a year at a brain facility in Bakersfield. He’s had multiple surgeries on his back and neck and recently had a metal plate put in his left arm; he will need surgery on his left ankle and a metal plate put in his right arm as well.

“I’m always in pain somewhere,” he said.

The accident also left him with an involuntary movement disorder. As a result, he’s had to have his mouth reconstructed twice. “I grind down my teeth to the gum.”

Hudson said at the time of his accident he’d been out of touch with Foster. “He never came to visit me in the brain injury center. He didn’t even visit me initially while I was at home,” recalled Hudson.

Foster, he said, surfaced just before he was awarded the settlement and began speaking with personal injury attorneys.

“I was high all the time because of the drugs. I mean, I wasn’t there,” Hudson said. “Lucas always kept on saying, ‘Do you trust them?’ about my lawyers. And then he’d say to me, ‘I got you,’ and I’d say, ‘Thank you, man.’”

“And then he went to my lawyers and said, ‘Hey, [Hudson] want[s] a conservatorship.’ I didn’t even know what conservatorship was. I agreed to a voluntary conservatorship, but it wasn’t me that initiated it.” Hudson made a similar claim in a court declaration.

Foster asserted otherwise, saying that Hudson’s court-appointed guardian ad litem, Robert C. Eroen, petitioned for a voluntary conservatorship in January 2012 on behalf of Hudson at his request, according to court records. Eroen did not respond to requests for comment.

Furthermore, Foster argued that, together with Hudson, they developed a plan for his living expenses and other matters. With Hudson’s “consent,” Foster said, he opened a conservatorship bank account that Hudson had access to. Foster said in court filings that he did not take any fees for being his conservator.

In December 2011, several months before the conservatorship was instituted, Hudson was given a psychiatric evaluation by Dr. James E. Spar, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

While Spar said that Hudson maintained his capacity to make decisions, manage his finances and resist fraud, he also found that his distractibility “could negatively affect his ability to track and manage his expenses and income.”

The former boxer said Foster made several significant financial decisions on Hudson’s behalf that he did not have the ability to fully understand, including purchasing a $1.39 million house for him in the Hollywood Hills.

In court proceedings, Foster said that he financed the house, taking a bridge loan from the seller. Hudson later contended that this was unnecessary, given the money left in his conservatorship estate.

After the conservatorship ended, Hudson said he spent several years battling to get the title put in his name. Property records reviewed by The Times show four transfer documents on the house were filed between 2012 and 2017 involving Foster, before it was transferred in 2017 to “Nigel Hudson, as Trustee of the Nigel Hudson Living Trust.”

By end of the 2013, Hudson said that he wanted to terminate the conservatorship.

“I wanted my life back,” he said.

In his legal filings, Foster said the decision was mutual, adding that they “agreed that the conservatorship should be terminated, and Hudson should continue the management of his own affairs without assistance from Foster.”

Foster petitioned the court to terminate the conservatorship in December 2013. Foster’s attorney arranged to have the financial accounting prepared. All parties, lawyers, guardian ad litem and Hudson signed off on it, and it was submitted to the court in March 2014. A month later, the court approved it.

However, the financial entanglement between the men did not end. Hudson alleged in court filings that Foster came to him on several occasions with personal “financial woes,” saying that he had “jobs coming up, but needed money to make sure the potential work turned into money.”

“I trusted him,” Hudson said. “That’s why I lent the money, because he’s telling me that he’s going to lose his house.”

Between January 2016 and February 2017, Hudson said that he loaned Foster $400,000, according to court documents.

But Hudson grew increasingly upset at what he viewed as Foster’s “empty promises to repay me,” he alleged.

Several text and email exchanges between the two men, copies of which were reviewed by The Times and included in the legal filings, detailed Hudson’s growing disillusionment.

In March, 2017, Hudson expressed his frustration, saying, “You have taken my friendship and situation and used it to your advantage, with no intention of paying me back.”

“I have nothing new to tell you,” Foster had told him, adding, “sending me emails is not gonna make anything go faster.”

He continued, “I appreciate your efforts on my behalf. But you apparently don’t remember mine, on your behalf. Or so it seems by your tone.”

As Hudson tangled with Foster over repayment of the loan, he said he discovered that Foster had misrepresented the payment of one of his medical bills two years after his conservatorship had ended. He learned of the discrepancy when his accountant, who was preparing back tax returns for 2013, asked for his medical expenses, according to Hudson’s attorney, Martin Horwitz.

One expense involved a $60,000 bill from UCLA that Hudson believed Foster had paid on his behalf. However, when he requested proof of payment for his tax returns, he found that, unbeknownst to him, Foster had negotiated the bill down to $54,704.64 and kept the nearly $5,500 difference for himself, according to court documents.

As tensions escalated, on April 26, 2017, Hudson filed a civil suit in Los Angeles Superior Court against Foster and his various companies, including Warp Films, to compel him to repay the borrowed money and to recover the difference in the amount paid to UCLA.

Foster denied Hudson’s allegations.

In several hours of video depositions taken in July 2018 and reviewed by The Times, Foster said that the $400,000 was not a loan, but rather an investment Hudson made in Warp Films.

After a bench trial in November 2019, the judge found for Hudson on three counts including breach of oral contract and theft, but did not rule in his favor on two counts involving breach of fiduciary duty and fraud. The parties negotiated a $700,000 settlement to be paid to Hudson, including attorney’s fees, interest and costs. The money was paid out over four installments.

But as Hudson battled Foster over his unpaid loans, another legal front opened up with the producer.

In April 2018, Miracle Mile Outpatient Surgery Center, which had treated Hudson following the accident, filed a motion against Foster in his former role as conservator, seeking enforcement of a court-ordered $10,000 payment.

A lawyer representing Miracle Mile sent Foster two letters in 2016 and 2018 saying it had not received payment of its bill.

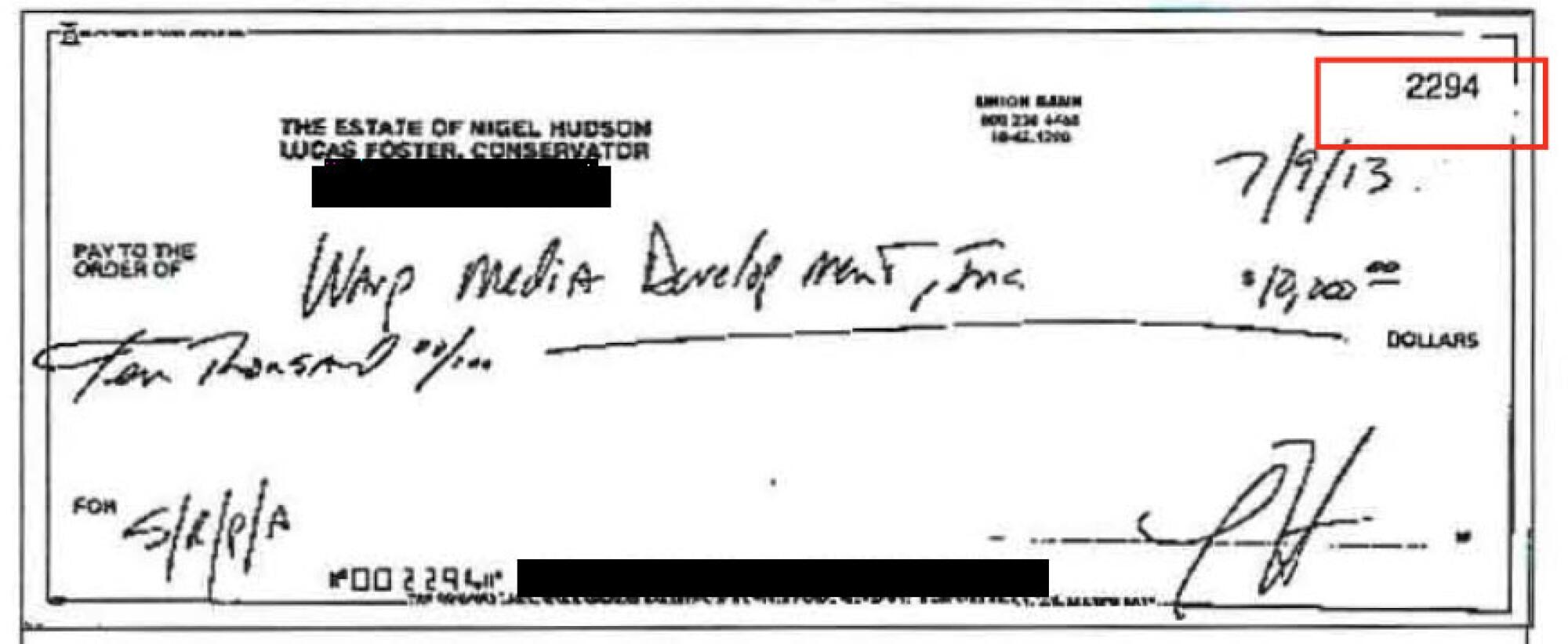

Hudson’s lawyer, Horwitz, subpoenaed the conservatorship’s bank documents, including check images.

When they compared the canceled checks against Foster’s entries in the schedule of payments submitted to the court, they alleged that a $10,000 check listed as being paid to Miracle Mile was in fact made out to one of Foster’s companies, Warp Media Development.

They further alleged that 28 checks totaling $558,169.47 and listed as being paid to third parties, such as Miracle Mile, were paid out to Foster or one of his companies.

Additionally, Hudson claimed that after Foster was discharged as his conservator and the court approved the final accounting, Foster had written four checks totaling over $60,000 to himself or his company.

On Aug. 30, 2018, Hudson filed a motion in the probate court to vacate the order approving the conservator’s final account, which, if approved, could lead to a full forensic audit of how the money was spent.

For his part, Foster said in court documents that the suit was “brought in bad faith” and that both Hudson and his guardian ad litem had signed off on the accounting. He alleged he had “advanced hundreds of thousands of dollars to purchase goods and services for Hudson’s benefit.”

Foster denied that he had defrauded his former friend, saying that Hudson knew that he expended funds through his various companies and “approved this plan.”

If Foster does not contest the appeal court’s ruling, it will go back to the probate court for a hearing.

“I want him to go to jail,” Hudson said.

Last year, Horwitz said he reached out to the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office, but in July they declined to pursue criminal charges against Foster, saying there was insufficient evidence to prove a crime beyond a reasonable doubt, according to an email reviewed by The Times.

Foster continues to produce movies. Last year, he made news for making a reimagining of “Children of the Corn” under COVID-19 protocols in Australia. His production company ANVL Entertainment lists 11 projects in development and one in production,”Morbius,” starring Jared Leto, on its website.

Hudson is currently living with a friend and is in the process of selling the Hollywood Hills house Foster purchased under the conservatorship to pay for his medical and legal expenses. “I would give up everything,” he said. “I don’t care about anything else. I just wish I had my life back.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.