How Alex Gibney pulled off a secret exposé of America’s COVID-19 failures in 5 months

- Share via

Alex Gibney was asleep when his phone rang at 2 a.m. last Friday. Roused from his slumber, the filmmaker answered the call to learn that President Trump had tested positive for the coronavirus. The news was so important that Tom Quinn, the founder of Neon — the production and distribution company about to release Gibney’s next documentary — felt he needed to reach out to the director in the middle of the night.

After spending a frantic five months pulling together a secret project focused on the United States’ response to the pandemic, Gibney thought he’d reached the finish line. That very morning, in fact, the trailer for the movie — titled “Totally Under Control” — was set to debut online. Now, Quinn wanted to discuss whether or not to move ahead with the plan.

“I think a lot of people reckon with this issue, in terms of: How do you express a sense of compassion for somebody who has caught a disease that could be fatal, but at the same time, consider issues of public interest?” recalled Gibney.

After a virtual sunrise meeting with his fellow directors, Suzanne Hillinger and Ophelia Harutyunyan, the team decided to proceed with the trailer launch. But they also had to reckon with how to handle Trump’s illness in the actual movie, which was set to open just two weeks later in drive-in theaters. (After its premiere at those locations this Friday, the film will be available via video-on-demand starting Tuesday and then to Hulu viewers on Oct. 20.)

Ultimately, no major changes were made to “Totally Under Control”: The filmmakers added an end card to the movie clarifying that one day after they’d finalized it for release, Trump tested positive for coronavirus. “It seemed like perfectly sardonic poetry that harmonized what we were saying in the film,” explained Gibney.

Gibney — no stranger to tales of manipulation (“Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief”), corruption (“Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room”) and dishonesty (“The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley”) — decided to make a coronavirus film in April. The idea was born out of his anger at “how badly the pandemic seemed to be bungled” in the U.S. He was feeling helpless, and wanted to channel that emotion into an investigation — one that could be seen by Americans before the presidential election.

But to complete a documentary in such a short time frame, Gibney knew he’d need help. So he reached out to Hillinger, an Emmy winner who’d worked on the New York Times docuseries “The Weekly,” and Harutyunyan, who had recently produced his Venice Film Festival selection “Crazy, Not Insane” (which HBO will release next month). With Gibney in Maine and the two women in disparate parts of New York City, the trio worked together using a virtual system called Collaborate that allowed them to make notes on emerging cuts of the project.

When it came to the interviews, the directors divided and conquered. Because of the pandemic, the filmmakers had to come up with various options for safely capturing footage. Some subjects were sent a camera rig that allowed them to communicate with the team over Zoom from the instant they retrieved it off the doorstep. Those who were comfortable meeting in person were protected from the directors with the aid of a shower curtain that had a hole cut in it. And in South Korea, the team was able to hire a 10-person crew because the infection rates had fallen so greatly. (Victoria Kim, The Times’ Seoul correspondent, was interviewed for the movie this way.)

This week, Gibney, Hillinger and Harutyunyan — none of whom were ever in the same room during the filmmaking process — convened for a video chat to discuss the movie’s biggest revelations, Trump’s recent diagnosis, and why the film won’t be playing indoor theaters.

Why did you feel it was vital for this film to be released before the Nov. 3 election?

Gibney: You want to have some way of holding officials to account and some information with which to do that. So here was a report card on the handling of the pandemic that people could reflect on prior to casting their vote. This was a film that was really about competence, number one. None of us wanted this to be seen as political, in terms of democrat versus republican. Also, in my own experience, I felt like it was a crime film. It was a crime of negligence and a crime of fraud. And those crimes, prosecuted in the court of public opinion, have a massive death toll.

Did anyone express concern about the rapid production timeline?

Gibney: There was some pushback from funders, like, “Why don’t you just wait? Relax? Tell it over the course of time when history will carefully reveal itself. You can tell a more textured version of this story.” I was like, “No. I want to tell this story now, when it matters. When you can look at what happened early on and render some kind of judgment. That should go into the calculus about how you cast your vote.”

How did you settle on whom you wanted to interview?

Hillinger: There were a lot of experts being interviewed on various news outlets and for various newspapers that did not have skin in the game — they were outside epidemiologists, some former public health officials. It was really important to try to get people on the inside who were in the room where decisions are made. Initially, I did the usual thing of sending out email proposals to the White House, to the task force, [the Department of Health and Human Services], [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]. I had the top list of the people I knew we wanted to speak to and I had several conversations with communication directors and press people and talked a lot about what our intentions were — how important it was that we hear what decisions were made and what information they knew. In the beginning, they obviously seemed very open, and we were trying to figure it out and it seemed like maybe there was a chance.

I had sources close to the CDC who were telling me, like, “People aren’t going to return your calls because they believe their phones are being tapped. They aren’t going to respond to your emails because they believe their emails are being watched.” It was scary.

— Suzanne Hillinger

But as it went along, more towards the end of the spring into the summer, there became a real sense that the CDC was being censored by the administration. I had sources close to the CDC who were telling me, like, “People aren’t going to return your calls because they believe their phones are being tapped. They aren’t going to respond to your emails because they believe their emails are being watched.” It was scary.

In the end, we had a few final phone calls with some high-level communications people. They never said “No, we won’t give you anybody to interview.” I had multiple conversations with folks at all of these agencies and then they just stopped responding. They knew that the film was going to come out in October, so they knew that eventually we were going to run out of time, and I think they just ran the clock.

If you had been able to interview President Trump, would you have taken that opportunity?

Gibney: You always want it. And what you want is people to walk through events step by step and tell their story. You’re always interested. And frankly, I encourage people to try to tell their stories the way they want to tell them. Once you get in the cutting room, you check the facts and see whether they’re lying to you or how often or whether there’s any moment when they’re not lying to you.

Isn’t that too late?

Gibney: No, it’s never too late. Once you’re in the cutting room, you can always find a way to put remarks in context so people know they’re lying to you. It’s hard to know in the moment if people are lying to you — you have to check.

Some people told you that they’d sit for interviews with you, but only after the election?

Hillinger: A lot of the conversations I had were: “We are not telling a political story. We are just telling the facts. And you have firsthand knowledge of the facts, and we just want you to share that with us. What did you bear witness to? Just give us your testimony, and that’s it.” And that was a really scary ask for a lot of people who are either career politicians or career public health folk who get government funding.

So how do you push back? Do you urge them to be on the right side of history?

Gibney: We tried to make that claim to Michael Caputo when he got on the phone with us representing HHS [as the assistant secretary of public affairs]. “You’ve gotta tell the story, and you’ve gotta tell the story so that the voters can decide.” But it won’t surprise you to learn that political figures don’t see it that way. They’re not thinking about history. They’re just thinking about the political utility of messaging in the moment because all they want to do is win. They’re not thinking about an obligation that they have to voters to tell the truth so that voters can decide. That’s not how the game works, unfortunately.

Harutyunyan: I was in touch with a Republican governor for three months. I was playing ball with them. They agreed to the interview and at the last minute, pulled out. Again, it just comes back to: “Will they give me PPE after seeing this interview? Will they give me swabs?” Because these states are still heavily relying on the federal government for materials and for tests, etc. So when you have someone at the top who, in a way, can decide they’re going to hurt someone for their personal reasons, obviously that’s very dangerous and you can’t play with that.

With so much news breaking every day, how did you decide what to include in the film? For instance, you play Bob Woodward’s recently released audio of Trump saying, in February, that he knew how deadly the coronavirus was.

Harutyunyan: We couldn’t just play catch-up with everything that was happening, but something that important, like the Woodward tape. ... We had obviously all assumed that the president knew, he was just downplaying it ... the tape was just the cherry on top, like, well, there’s evidence he knew, he says it himself. Luckily we were still editing so we could naturally include it.

Hillinger: We knew that chasing the news could be dangerous when you’re making a film about something that is still unfolding. You’ll never finish a film if you feel like there’s still information coming out. We had these amazing associate producers that were working with us who built these timelines — every event that happened starting in January, every announcement that was made, every decision that was made, every sort of key moment. We were able to read through it as a narrative and really crystalize what were the moments that a really sharp turn was taken that we could have gone in one direction and we went in another. To be able to hone in on those kept us on track. We knew there were key decisions made in the first three months that have consequences that keep affecting Americans to this day.

Have you been surprised by how Trump has dealt with his COVID-19 diagnosis?

Harutyunyan: Honestly, I was surprised early on that Trump hadn’t gotten COVID. I was like, “He’s not wearing a mask. He’s not socially distancing. How is he not getting this virus?” And then when we found that everyone around him is getting tested every day, and anyone who goes to meet him is getting tested — you realize the privilege that he had. A lot of people couldn’t even get a test, and here was the president of the United States making everyone get a test before meeting him because he didn’t want to wear a mask and he didn’t want to socially distance.

Gibney: It was a jaw-dropper. There’s a famous, probably apocryphal story about Edward R. Murrow who famously used to smoke on set all the time with a dark, black set heavily backlit so you could see the smoke. I believe a lot of his shows were sponsored by cigarette companies. And when he came in to see a doctor — and he ultimately had lung cancer — the doctor said “I’ve been waiting for you.” Everybody should have been waiting for Trump to get coronavirus because he was being so reckless about it and making such an issue out of not wearing a mask and not taking precautions for political reasons. And then the virus put the lie to that kind of political mendacity.

His willingness to put so many people physically at risk for a photo-op is the ultimate metaphor for how he’s put politics above public safety over and over and over again. And as a result, more than 200,000 people are dead.

— Alex Gibney on President Trump

Hillinger: I think actually more shocking than him getting the virus, to me, is that he hasn’t changed his messaging that it’s not serious. I think there is utter disregard for his privilege. The fact that he was able to get admitted to Walter Reed. He got several rounds of remdesivir, which is extremely expensive. He got put on steroids that most people don’t receive until they’re very sick. He got round-the-clock care. He was probably put on oxygen. Him downplaying the severity of this virus that he now has is also downplaying the access that most Americans have to public health. Most Americans got sick with this and were told to not even go get tested. Most Americans were told to stay home until they had trouble breathing. It’s just shocking that there continue to be no lessons learned here.

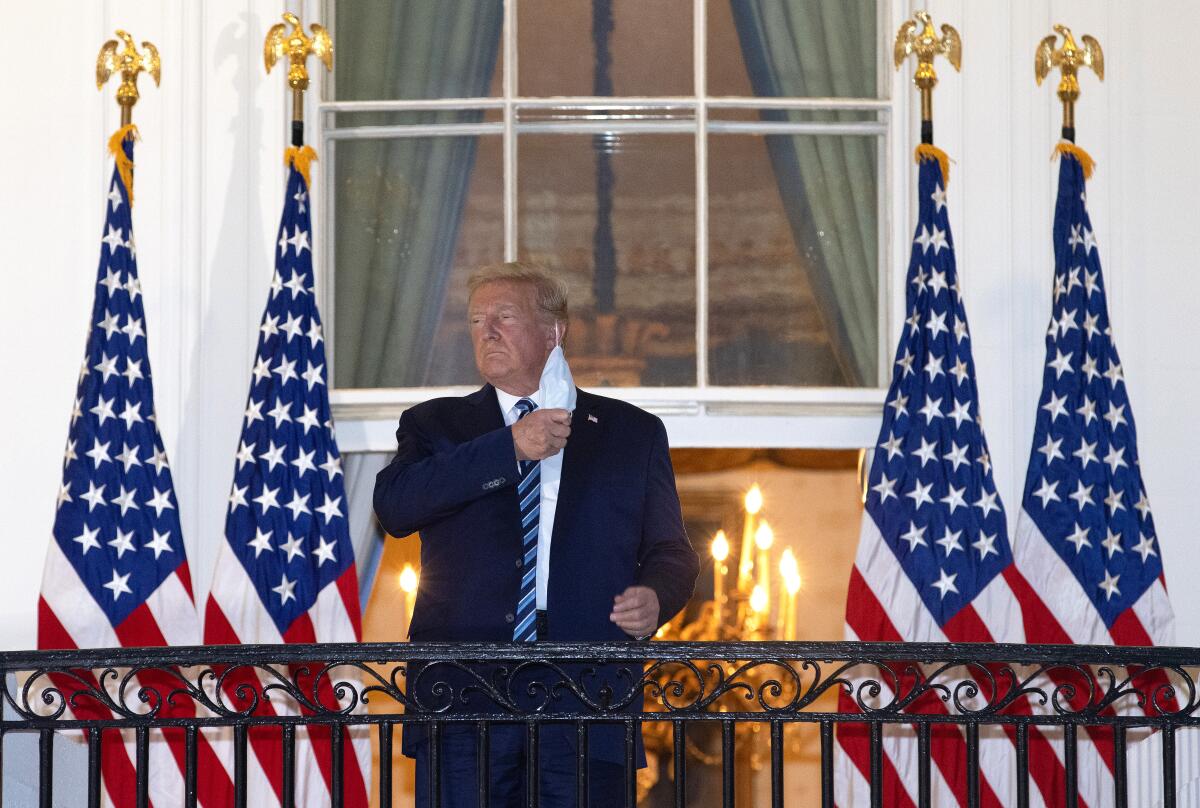

Gibney: But it’s such a powerful metaphor for how he’s handled the virus from the very beginning. The primacy of political messaging over everything. That Evita-like moment where he pulls the mask off but you can see he’s barely able to breathe because his lungs are so compromised. His willingness to put so many people physically at risk for a photo-op is the ultimate metaphor for how he’s put politics above public safety over and over and over again. And as a result, more than 200,000 people are dead.

If elected, do you think Joe Biden will be able to change the course of the pandemic in the U.S.?

Gibney: The proof is in the pudding. If Biden wins, come January 20th when he takes over, who is he going to appoint to run these critical institutions? Who is he going to surround himself with in order to be able to have a reckoning to solve these ongoing problems? There’s always a challenge in terms of holding politicians to account. But so far, he seems to have an understanding of the importance of science and fact-finding, and that in and of itself gives me some confidence.

Why did you opt to bypass movie theaters in releasing the documentary?

Gibney: We felt only drive-ins are appropriate at this moment in time in terms of safety issues. Sadly, that’s where we’re at. It didn’t have to be this way. It’s still unsafe. You’re putting too many people in close proximity in indoor locations that are potentially not well-ventilated enough. It just seemed like something that would be too risky at this point.

Do you honestly believe this film has the power to convince a Trump supporter that Trump badly handled the pandemic response?

Gibney: Look, I think there are people who will believe in Trump and follow Trump wherever he goes, no matter what is said. But I think there are people for whom this can and will make a difference. And I think also there are people on the sidelines who are disgusted with the government and wonder if it matters. There’s an obligation that we have to try to tell the truth on an important story, and I hope that people will look at a story carefully put together based on facts and render a judgment based on that. You’ve gotta hope and believe in that. But that said, obviously, I’ve done films in the past on the prison of belief ... and the power of belief is enormous for some people and can’t be shaken by facts. Trump has done his best to try to destroy the power of facts and to destroy institutions and the rule of law, and we’re seeing the result. But I do think a story like this can make a difference.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.