- Share via

In the summer of 2014, Canadian actor Simu Liu — still a few years away from his breakout role on the comedy series “Kim’s Convenience” — sent off a tweet to what he jokingly describes as “maybe 14 followers.”

At the time, Iron Man already had three movies of his own in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Thor and Captain America had two apiece. The blockbuster comics-inspired series was only making room for one kind of hero: white men. (Actors named Chris were in high demand.)

“Now how about an Asian American hero?” Liu asked, tagging Marvel. He hardly expected a reply.

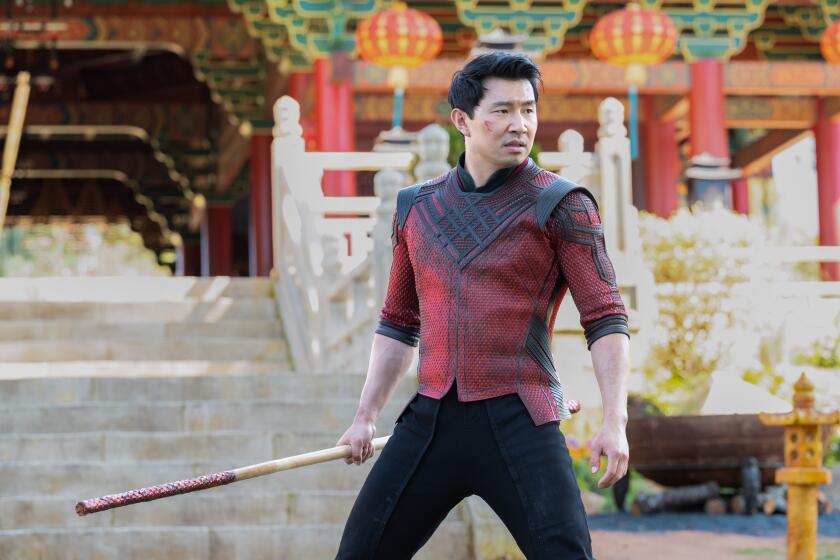

This week, after 24 films and over a decade, Marvel finally delivers its first Asian-led superhero stand-alone. Directed by Destin Daniel Cretton (whose decidedly non-blockbuster resume includes “Short Term 12” and “Just Mercy”), “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” sees Liu stepping into a career-making turn as the eponymous Shang-Chi, a hero running from the shadow of his warlord father (played by simmering Hong Kong screen icon Tony Leung).

Now how about an Asian American hero?

— Simu Liu, 2014

What was behind that tweet all those years ago? A mix of frustration and desire familiar to anyone who’s ever felt pushed to the margins of pop culture, or culture at large. “You were starting to see the MCU forming into what it is today, feeling like, ‘Oh my God, this is incredible,’” Liu described on the L.A. Times’ Asian Enough podcast (listen to the full episode here). “And how much more incredible would it be if I saw myself reflected on that screen in some way?”

Now Liu, 32, is seeing himself reflected in the biggest ways: on billboards, on posters and on the big screen in a wuxia-inflected superhero origin story filled with otherworldly heroics. He’s prepared for the moment and the responsibility that comes with visibility, using his platform to speak out for the Asian American community and readying to springboard his own projects.

But the stakes are high when you’re making history, even more so in a pandemic. Opening exclusively in theaters, “Shang-Chi” won’t arrive on the Disney+ streaming service for 45 days, a first for a Disney-produced film during COVID-19. Liu now has over 1 million followers on social media, and when Disney CEO Bob Chapek recently referred to its release strategy as “an interesting experiment,” the star subtweeted a rebuke: “We are not an experiment ... we are the underdog; the underestimated. We are the ceiling-breakers.”

Whether or not it was a “misunderstanding,” as Marvel head Kevin Feige said — when smoothing over the pre-release bump at the film’s world premiere — Liu won’t confirm. He’s focused on rallying audiences around the film, which could nudge the door open wider for inclusive stories to come — or not. Projected to easily win the Labor Day weekend box office, “Shang-Chi” comes armed with stellar reviews and a 91% Rotten Tomatoes score, but audiences are much less familiar with the character than, say, Black Widow. (July’s release of the female Avenger’s first solo film brought in $80 million domestic in its first weekend, and was also available on Disney+.)

Reclaiming Shang-Chi

That obscurity, however, is partly what allowed the filmmakers to rewrite Shang-Chi in their own vision. And the quality that landed Liu the role of a lifetime, says Cretton, was the relatability he brought to the character, which they hope fans will connect with. (The perfectly-executed backflip he landed in his audition didn’t hurt either.) His Shang-Chi is easygoing, capable and charismatic, and like many Asian Americans, torn between cultures — just not the ones you might think.

The film opens post-”blip” with a few nods to the larger MCU, with Shang-Chi living under the radar as “Shaun” and working as a San Francisco hotel valet with his slacker best friend Katy (Awkwafina). When enemies attack, Shang-Chi reveals his true abilities and faces what he’s been hiding from: A villainous dad, mystical family legacies and his own dark secrets marred by trauma and loss.

The sweeping plot takes Shang-Chi and Katy to an underground fight club in neon-lit Macau run by his sister, Xialing (newcomer Meng’er Zhang), and ultimately beyond the earthly plane to the village of Ta Lo, an interdimensional land populated by warriors and connected to his late mother. It’s there where the fate of the world — and Shang-Chi’s heroic destiny — hinges, alongside a radiant Michelle Yeoh and creatures of Chinese legend.

With influences drawn from Jackie Chan, Zhang Yimou and Ang Lee movies, “Shang-Chi” marks another major moment for East Asian representation in Hollywood after 1993’s “The Joy Luck Club,” 2018’s “Crazy Rich Asians” and last year’s “Mulan.” “Shang-Chi” even takes inspiration from a Stephen Chow fave to solve one of its biggest practical questions: rather than depict the titular Ten Rings as finger adornments, as in the comics — similar to the bejeweled Infinity Gauntlet — the weapons are rendered as powerful bracelets a la the iron rings used by Chiu Chi-ling’s Tailor in “Kung Fu Hustle” (a poster of which eagle-eyed fans will spot on Shaun’s bedroom wall).

It’s a superhero blockbuster told on a Marvel scale with a predominantly Asian and Asian North American cast onscreen, made by Asian American talent. But just a few years ago, when screenwriter Dave Callaham (“Wonder Woman 1984”) got the call from Marvel, he didn’t think they were serious about making a movie about an Asian superhero. “I said, ‘I didn’t know they had those,’” he quipped.

It was 2018, the year of Ryan Coogler’s “Black Panther,” a watershed blockbuster and multiple Oscar-winner that would open the door to an unprecedented era in the franchise. Marvel had already lined up an increasingly inclusive slate featuring “Captain Marvel,” “Black Widow,” “Eternals” and a “Black Panther” sequel. Callaham was excited at the prospect of bringing an Asian character into the universe — then producer Jonathan Schwartz told him they were eyeing Shang-Chi, a chopsocky 1970s comics character with ties to the cliche-ridden Fu Manchu who was also known as “The Master of Kung Fu.”

“As an Asian American guy, it seemed dangerous that the first presentation of an Asian American superhero would be a kung fu master,” said Callaham. Producers, however, acknowledged that the source material leaned into problematic tropes, leaving ample room for updating. Callaham felt emotional at the prospect of being able to weave his own perspective into a project of this scale. It was the first time anyone had asked him to write his own story.

Even after he signed on and started working on “Shang-Chi,” he had a hard time keeping faith that it would actually be made and not left to languish in a Marvel IP vault. “It was this internalized experience I had as an Asian guy,” said Callaham. “40 years of me not believing that Hollywood was ever going to do this put me in this position where I thought, maybe if I do a great job on the script ... someday, they might make a ‘Shang-Chi’ movie.”

A month in, Schwartz brought up Australia. “I said, ‘What’s in Australia?’ ‘That’s where we’re going to shoot the movie.’ And I went, ‘You’re going to make this movie?’ They were always serious about it,” said Callaham. “It just was hard for me to believe.”

Representation matters

Looking back now, Marvel Studios President Feige wouldn’t necessarily build the $23 billion-grossing, Avengers-centric MCU any differently if he could — “because knock on wood, it’s been working out pretty well.” But Feige, who like the vast majority of studio heads and senior executives in Hollywood is white and male, admits that he wasn’t focused on how meaningful it was for underrepresented audiences to see themselves reflected onscreen.

“The importance of being able to see yourself up on that big screen with a big superhero company logo and somebody that looks like you as the title character has always been important, is more important than ever — and honestly, as a white guy, was something I took for granted,” he said. “I never thought Luke Skywalker or Han Solo looked like me. But I took for granted subconsciously that they did, certainly more so than somebody who’s not a white guy.”

The importance of being able to see yourself up on that big screen... is more important than ever — and honestly, as a white guy, was something I took for granted.

— Marvel Studios head Kevin Feige

He’d been particularly moved by an online video of “Black Panther” fans reacting to seeing Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong’o and the rest of the cast on the film’s poster for the first time, and recently rewatched it ahead of the “Shang-Chi” release. “I remember somebody saying, ‘Is this what white people feel like all the time?’ That was an eye opener for me.”

As Feige puts it regarding “Shang-Chi” and the cultures it represents: “This is not a Chinese movie. This is not an Asian American movie. This is a Marvel movie.” But when it came to bringing “Shang-Chi,” originally created by Steve Englehart and Jim Starlin, into the 21st century, hiring filmmakers who could build a compelling world and characters and bring their lived experiences into the process was a priority.

Cretton, however, never intended to direct a superhero movie. Coming out of the indie film world, he first became known for helming festival darlings “I Am Not a Hipster” and “Short Term 12” before leveling up to character-driven studio dramas. Prior to “Shang-Chi,” he’d adapted the life story of civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson into the awards season contender “Just Mercy” starring Michael B. Jordan.

Tackling the tropes

Meeting with Marvel, Cretton initially wanted to caution against falling into stereotypical traps with the MCU’s first Asian lead. Then conversations led to a deeper investment in Shang-Chi’s fraught relationship with his estranged father, the soulful and terrifying Xu Wenwu — who, through Leung’s performance, becomes a tragic figure of great torment and romance. He eventually jumped at the chance to create the kind of iconic screen superhero he didn’t have growing up, signing on to direct, and began working on the screenplay with Callaham as well as his “Just Mercy” collaborator Andrew Lanham.

The filmmakers made a list of stereotypes they wanted to dispel. One was to portray Asian people as funny, charismatic and charming. Another was to show that Asian men can be romantically viable — a matter for another film with the hero, perhaps, since Shang-Chi is the rare Marvel lead who does not have a love interest. “We landed where we landed for a variety of reasons,” explained Callaham, “but it’s not something that we’re planning to not examine.”

But the question remained: How do you make a movie about an Asian martial arts master that doesn’t delve into tropes? For starters, they decided to present Shang-Chi’s fighting skills not as a superpower, but the result of his father’s relentless and cruel training. And while Liu’s ability to do many of his own fighting and stunts was of enormous benefit — guided by a stunt team led by the late Jackie Chan protege Brad Allan — the inner life he brought to the character mattered more.

“It was important to make sure that his personality was something unlike we’ve seen before — that this is someone who looks and sounds like me and my friends, and I could fully relate to him and ground him,” said Cretton. Once Liu was cast following a screen test with Awkwafina just days before being announced onstage at Comic-Con 2019, the trio solidified their shared vision for the character.

“We’re not here to make another martial arts movie about a foreign guy who comes in and doesn’t really have an arc, doesn’t have a personality other than the fact that he’s from a different place and he speaks English differently,” said Liu. “We wanted this to be a real story where the central character goes on a journey and is three-dimensional and it is very much about his relationships, more so than just the fighting.”

Make it personal

As with any community or diaspora, their own lives and backgrounds as North American men of Asian descent were vastly different. Liu, born in Harbin, China, had immigrated to the Toronto suburbs as a child with parents who strained to understand him and his desire to be seen. Cretton, who is Japanese American, grew up in Hawaii where he never felt like an outsider — until, that is, he moved to California. Callaham was raised in the Bay Area, where he’d often visit his grandmother in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The shared throughlines they found in their disparate experiences, in turn, helped to inform Shang-Chi’s journey.

“The common thread that we all had felt at one time or another is this feeling of insecurity. Of not being the coolest person in the room. The subtle condescension that often comes our way regardless of what our professional trajectory is,” said Cretton. “Watching Shang-Chi learn to finally look at his pain, at the moments in his life where he felt the smallest, when he was pushed down, when he felt like he wasn’t a normal, regular person — when he looks back at those moments and learns how to redefine them and turn them into a superpower, for me that was very therapeutic.”

It’s at Katy’s family’s home that the movie first relishes in details that Asian American audiences might get even if others don’t, which Feige compares to Marvel superfans recognizing comics references that might otherwise go over the heads of general moviegoers. Shang-Chi arrives one morning and kicks off his shoes on the way in. Inside, the family is eating jook for breakfast — a meal Callaham originally wrote into the script as “Gung Gung eggs,” a favorite dish of his grandfather’s.

Simu Liu teams up with director Destin Daniel Cretton for a superhero origin story with more family psychodrama and better action than the Marvel norm.

Later when Katy and Shang-Chi head to Macau, she demurs that her Mandarin isn’t so good, to which Ronny Chieng’s over-the-top emcee Jon Jon says: “It’s OK, I speak ABC” — or, “American-born Chinese.” And when Shang-Chi and Katy relate the story of how they became friends, it’s because she defended the recent immigrant kid in high school when he was being bullied “for all the reasons we always get bullied,” a line that rings painfully true after the rise in anti-Asian racism seen last year.

However moviegoers see “Shang-Chi,” Callaham hopes the character’s debut in the MCU lands with the same impact other heroes have had on young fans. “I think it’s critical for young people especially to see Shang-Chi for the first time in the same place they saw Steve Rogers or Tony Stark or T’Challa — I think it needs to be demonstrated that these are all equal faces,” he said. “And whatever comes next, I’m hoping that he opens doors for a lot more of these characters.”

Times staff writer and “Asian Enough” co-host Tracy Brown contributed to this report.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.