- Share via

Don Bluth first found his “laughing place” — a term he uses to refer to an intangible mental refuge from the drudgery of existence — in the films of his lifelong hero, Walt Disney.

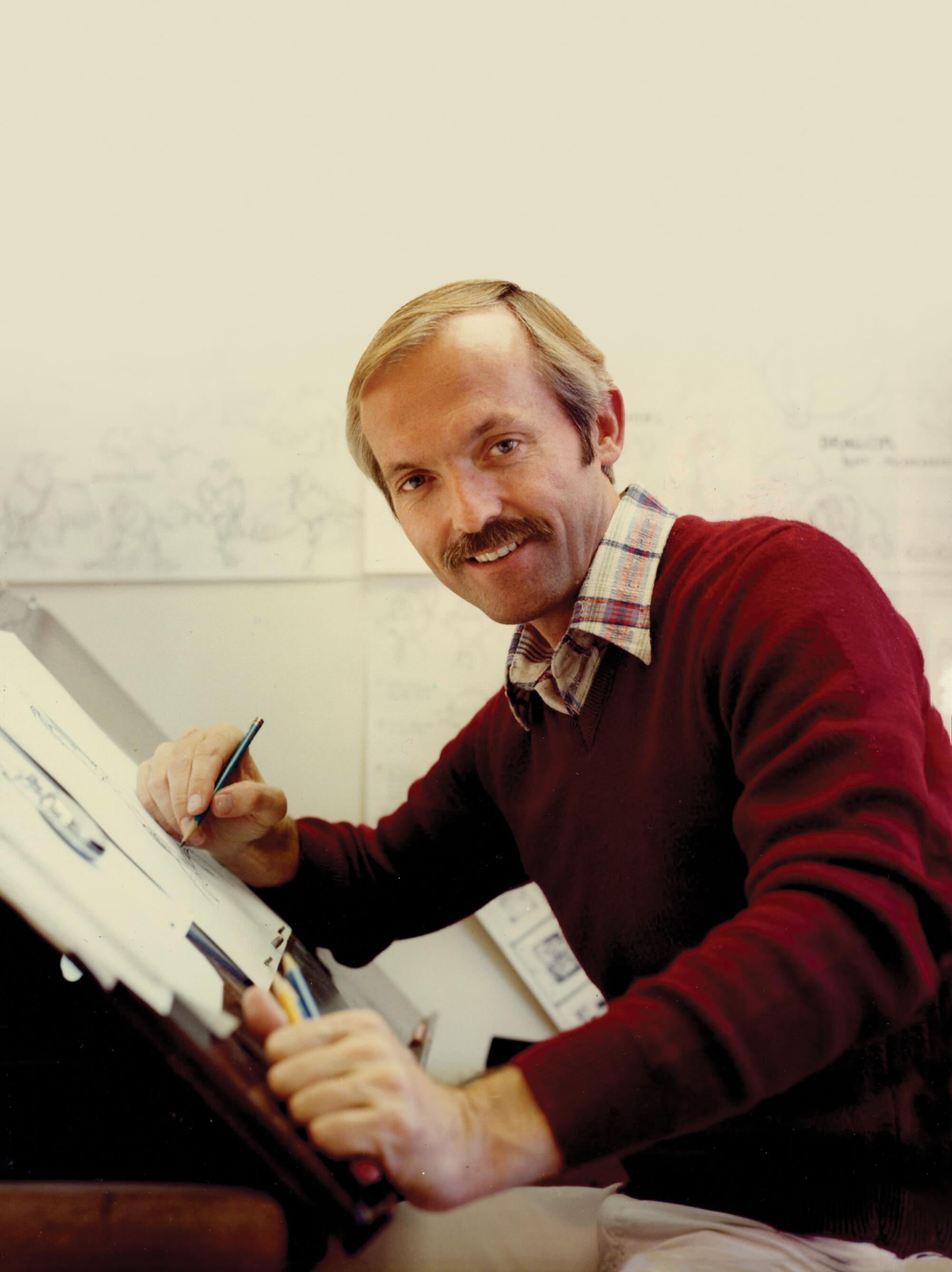

Today an animation legend in his own hard-fought right, Bluth, 84, recalls riding his horse into town to watch movies at the local cinema as a farm boy in Payson, Utah. Born within just a few months of the premiere of Disney’s first animated feature, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” in 1937, his life has run parallel to the history of the medium in the U.S.

“Animation brought my spirits up. Everything about it said, ‘That’s where you should go,’” Bluth told The Times over the phone from his home in Scottsdale, Ariz., where he has lived and worked for several decades.

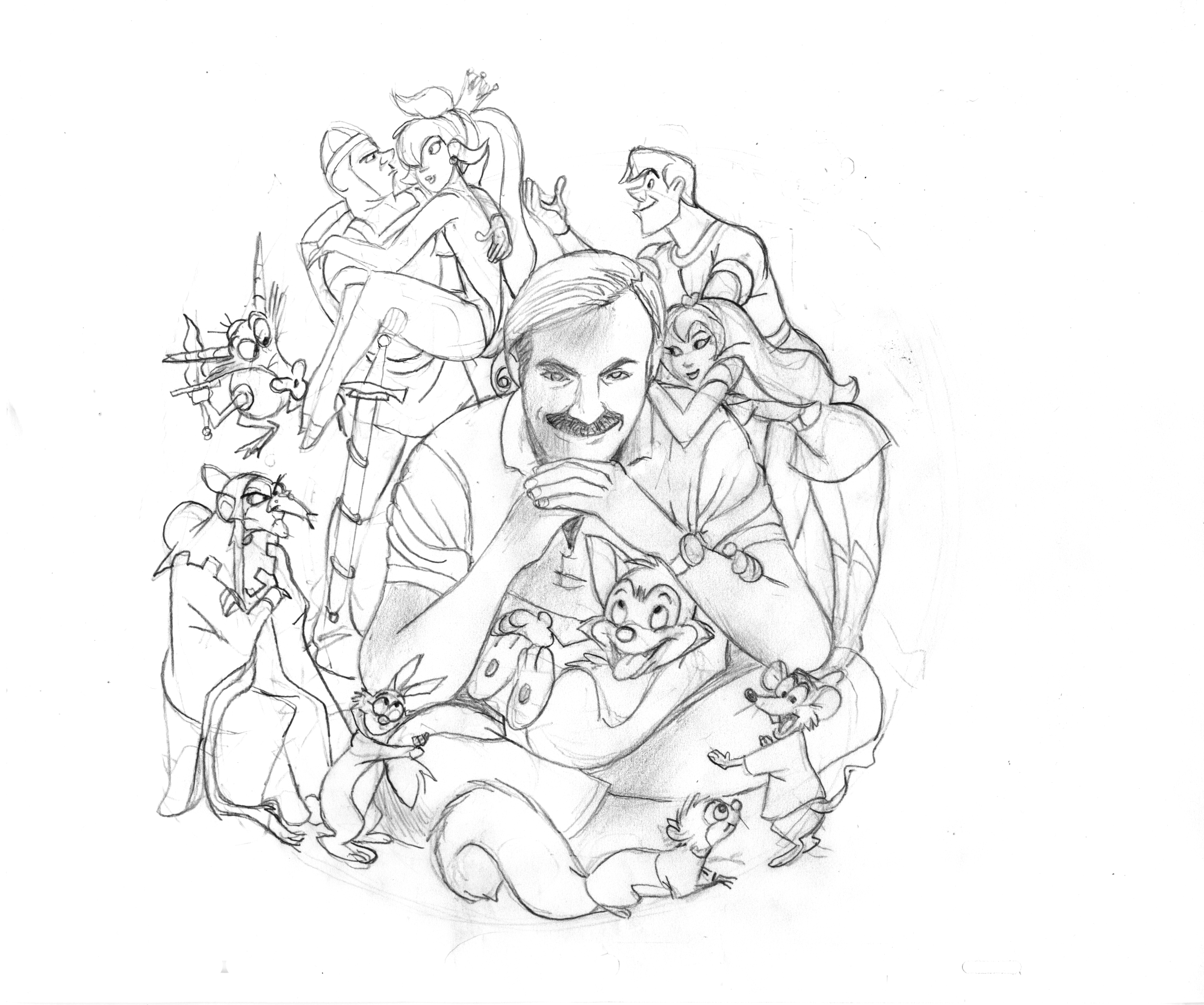

Led by charming mice, adorable dinosaurs, determined princesses and myriad other fantastical beings, Bluth’s collection of animated features rivaled the output of Walt Disney Studios during the 1980s and ‘90s in their artistic quality, all of them magnificently hand-drawn, and, even more significantly for Bluth, in their thematic substance.

Of the 11 feature projects he realized over 20 years of intense dedication — often working with limited budgets and against the grain of the industry — some of the most illustrious include “The Secret of NIMH” (1982), “An American Tail” (1986), “The Land Before Time” (1988), “All Dogs Go to Heaven” (1989) and “Anastasia” (1997).

For the animator raised in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, these wondrous fables were the manifestation of his divine purpose meant to be shared with the world.

“I discovered over the years that the more you give, the more you get. When you’re in the service of people and you help them out, there’s a source of joy that comes from that,” he said. “If I was going to make an animated film, I didn’t want to just make people laugh. I wanted them to have something to take home that could make their lives a little better.”

Compiled of professional anecdotes and innermost thoughts, Bluth’s recently released, tell-all autobiography, “Somewhere Out There: My Animated Life,” opens the vault of his memories in his own uniquely philosophical words.

“I’ve had such a wonderful life and one day I just said to myself, ‘I should write down a few things,’ not with the idea of making a book, but just for my own enjoyment, just to write down everything that’s happened in my life,” he explained.

In time, a friend suggested he should turn the inspired loose writings into a memoir and Bluth thought of it as an opportunity to disclose the greater truths he believes in.

“For years and years, all I’ve talked about is animation, the characters, and all the usual questions I get asked, but I’ve never revealed who I am, like the man behind the curtain in ‘Wizard of Oz.’ So I said, ‘If at my age I’m going to talk to people, I need to tell them exactly what I feel and what I’ve gone through,’” he said. “That spiritual part has a great deal to do with what I did in the movies, but I’ve never fessed up to that before.”

The Disney era

For a young and reserved Bluth, Walt Disney was an archetype of masculinity he could aspire to. Not an athlete or a physically imposing figure, but an artist with a vision that resonated with him. At 18, Bluth was hired by Disney’s studio as an in-betweener — the artist who draws the middle frames in animation to make the action smoother — on the gorgeous princess saga “Sleeping Beauty.”

Bluth saw Disney in the flesh on two occasions during his time at the studio. First from afar while hiding behind some bushes with friends as his idol shot an episode of the “The Mickey Mouse Club.”

“It was like meeting Santa Claus for the first time, a very legendary image,” Bluth remembered.

And once more after embarrassingly running into him and falling to the ground during a volleyball game. This time Disney spoke to him.

“I looked up and it was like the sun was behind him and I didn’t know who I bumped into, but then I heard his voice and he said, ‘If you will slow down young man, you’ll go a lot further.’ He stepped over me and walked on down the street.”

Despite his profound admiration for Disney’s storytelling prowess, Bluth never aimed to imitate him. “Everyone kept saying, ‘I’m going to be the next Walt Disney,’” he recalled of some of his colleagues. But he was convinced that if their motivation was strictly financial, and not guided by a strong work ethic and spirituality, they would fail.

“I didn’t want to be Walt. There was only one of those, and I’m me. I liked the medium that he worked in and I wanted to see if I could work in it and be successful,” Bluth said.

For 20 years, Bluth worked on a variety of Disney projects, including “The Sword in the Stone,” “Robin Hood,” “The Rescuers” and “Pete’s Dragon,” on the latter as the animation director for Elliott the dragon.

But in 1979, Bluth and several other animators solemnly decided to abandon the studio. Given the direction the operation was taking after its creator’s death in 1966, according to Bluth, they saw no other way to keep the art of animation alive and thriving. At the time the company was working on one of its biggest disappointments, “The Black Cauldron.”

“Someone asked me one time, ‘Why did you leave Walt Disney Studios?’ And I said, ‘Because Walt left Walt Disney Studios.’ I began to see that the magic he had created was crumbling. It became a corporation with lots of stockholders,” Bluth said. “I read that Walt said once, ‘The worst thing I ever did was go public.’ Suddenly you don’t have autonomy anymore. You’re beholden to the stockholders who really only want profits.”

The road to ‘NIMH’

On their own now, Bluth and about 17 others — including his most loyal collaborator, Gary Goldman, with whom he co-directed many of his features — taught themselves how to put a film together. They were animators learning to become storytellers and filmmakers. Their initial efforts to push animation forward, which had started in Bluth’s garage before their formal resignation from Disney, resulted in the short film “Banjo the Woodpile Cat.”

That calling card earned them the resources to make “The Secret of NIMH.” Bluth’s first animated feature as director was adapted from the book “Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH,” under a newly formed studio, Don Bluth Productions — which changed names multiple times over the years.

“The cost to make ‘The Secret of NIMH’ hand-drawn was $6.5 million,” he said. “Not $150 million, not $300 million like today.”

Released during the emblematic summer of 1982, when “E.T. the Extra‑Terrestrial,” “Tron” and “Blade Runner” also debuted, “The Secret of NIMH” followed the desperate plight of a mother, Mrs. Brisby (voiced by Elizabeth Hartman), to save her children from imminent death. She enlists the help from rats who were subjects of scientific testing.

“Those rats became intelligent, and with intelligence comes moral values,” Bluth said. “You can’t just go on being immoral if you’ve got intelligence in your head, there’s no wisdom in that. It seemed like a delightful story, and there’s a lot of conflict in it.”

With mature themes and impeccable craft, the film received critical praise, but underperformed at the box office. More than a decade later a follow-up to the same narrative was produced without Bluth’s involvement.

“What I really lament is that I would love to have done the sequel to ‘NIMH,’ but they said, ‘No, it’s ours now. We’ll do it.’ And it was not very good,” Bluth added.

‘The Land Before Time’

Eager for new projects, Bluth took on “Dragon’s Lair,” a revolutionary video game for which they animated the entirety of the playable narrative as if it were a film, followed by a deal with Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment that yielded two features: “An American Tail” (1986), about a family of Russian Jewish mice coming to the U.S., and “The Land Before Time” (1988).

The latter, a fan favorite, is a prehistoric family adventure about a group of young dinosaurs, led by Littlefoot (voice by Gabriel Damon), searching for their families after they have migrated to a new region. Aware of the love for the film, but still self-critical, Bluth believes the concept itself worked better than the finished product.

“To me, the story is more grand and more glorious than the animation. Although I think the animation was very difficult,” he said about “Land.” He has not seen any of the more than a dozen sequels that were made, viewing them as another example of greed tainting the creative process in animation by mass-producing instead of handcrafting singular works.

It was during production on “Land” that Bluth and company resettled their studio in Dublin, where he completed a handful of features over a short period of time beginning in 1989: “All Dogs Go to Heaven,” the live-action/animation hybrid “Rock-a-Doodle,” “Thumbelina,” “A Troll in Central Park” and “The Pebble and the Penguin.”

Pleased with the body of work he was able to amass after leaving the House of Mouse, Bluth harbors no hard feelings. But obviously he noticed the studio’s habit of rereleasing some of its most beloved titles to compete with and diminish the release of Bluth’s original features.

Many years after the 1979 exodus, while Bluth was set up in Ireland, Roy E. Disney, the nephew of his hero now in power, presented him with a way back into the flock. He called Bluth and flew to meet him at a pub. Disney extended the type of offer he expected no one could ever refuse.

“He said, ‘I want you to come back to the studio. All is forgiven. We’ll make it up to you.’ And I said, ‘Well, Roy, I have 360 employees here. They all brought their families here to Ireland.’ And he says, ‘You can’t win this Don. We’ll crush you.’” To that less than subtle threat, Bluth replied, “Maybe you need us. If we keep trying to compete with you, what might happen is you will work harder to make your pictures better.”

“It was always a game of getting the money,” Bluth recalled. “But what’s phenomenal is that we made 11 full-length animated films before the Disney machinery was able to throw sand in our machine.”

‘Anastasia’ and ‘Titan A.E.’

Bluth’s Ireland chapter concluded when Bill Mechanic, then CEO of Fox Filmed Entertainment, proposed that he and his team relocate to Phoenix and establish Fox Animation Studios. Their first venture, “Anastasia” (1997), a dazzling musical about the lost heir of the Romanov family in czarist Russia, became the biggest box office success of Bluth’s career, grossing $140 million worldwide.

The filmmaker’s most indelible memories of the production include hiring artists from the Philippines due to a wage war between Disney and DreamWorks that created a shortage of stateside talent; passing on Johnny Depp for the role of Dimitri because the actor wanted the character to look like him; shooting an entire live-action iteration of the film with theater actors, and the use of digital technologies to enhance key sequences like the “Once Upon a December” number.

In an ironic twist of fate, “Anastasia” became one of the titles now owned by Disney after the acquisition of the 21st Century Fox Company in March 2019. Bluth took the news with humor and believes that his creation will endure the change of ownership for the better.

“As long as people see it and enjoy the story and it enriches their lives, I’m okay with that. I know that a movie needs to be taken care of and I think Disney will do that very well,” he said. “Now, if they start marketing her as just another Disney princess, I should probably frown a little, but I think it’s in good hands right now.”

About his last feature film to date, the action sci-fi 2D/CG hybrid “Titan A.E.” (2000), a troubled endeavor from the onset that effectively ended Fox Animation Studio, Bluth admits that it wasn’t the right fit for him. Yet, even within the constraints of a task imposed by the studio higher-ups, he approached it with the sincerest intention of making it as good as it could possibly be.

“It was like if a guy fell from the trapeze and someone said to me, ‘Don, I know you’re not used to the trapeze, but go up there and just swing about, you’ll be okay.’ [Laugh]. It was sort of me doing something that wasn’t really in my DNA,” Bluth said. “I tried as much as I could to make it beautiful to look at, but the concept was more of a live action picture than it was an animated story.”

In the years since the “Titan A.E.” ordeal, Bluth turned to teaching via Don Bluth University, an online school, as his way to pass on the artistic wisdom he acquired along 40 intense years in the industry. A hardliner of traditionally hand-drawn animation, he hopes to preserve the discipline he adores through education.

“In hand-drawn animation, you’re the animator called upon to create the figure, the actor, the character, simply with a pencil and an eraser,” Bluth explained. “Now over in CG, that character is a puppet inside the computer. What you’re called upon to do is puppeteering. Animation means to bring to life, so I suppose they’re bringing something to life, but it’s not that great feeling that comes from creating life with your pencil.”

Asked if he could identify any themes that followed him throughout the many stories he told in animation, Bluth immediately knew what the connecting thread always was.

“Every movie that I’ve ever made, if you look at it closely, is about going home. Those are thematic things that seem to push their way inevitably into all my movies,” Bluth said. “Home isn’t necessarily the soil that you walk on, but where your spirit can breathe, where your loved ones are. It’s where all your memories are. It’s something that’s very dear.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.