What’s the real-life Hollywood history behind ‘Babylon’? We asked the experts

- Share via

Warning: The following article contains modest spoilers about the fate of some of the characters in “Babylon.”

The Twenties may have roared, but on film they were silent until “The Jazz Singer.” Released in 1927, the Al Jolson classic launched the era of talkies, an epic transformation requiring studios to remodel stages for sound, revise set protocols for cast and crew and reassess what sort of material worked best with the new technology.

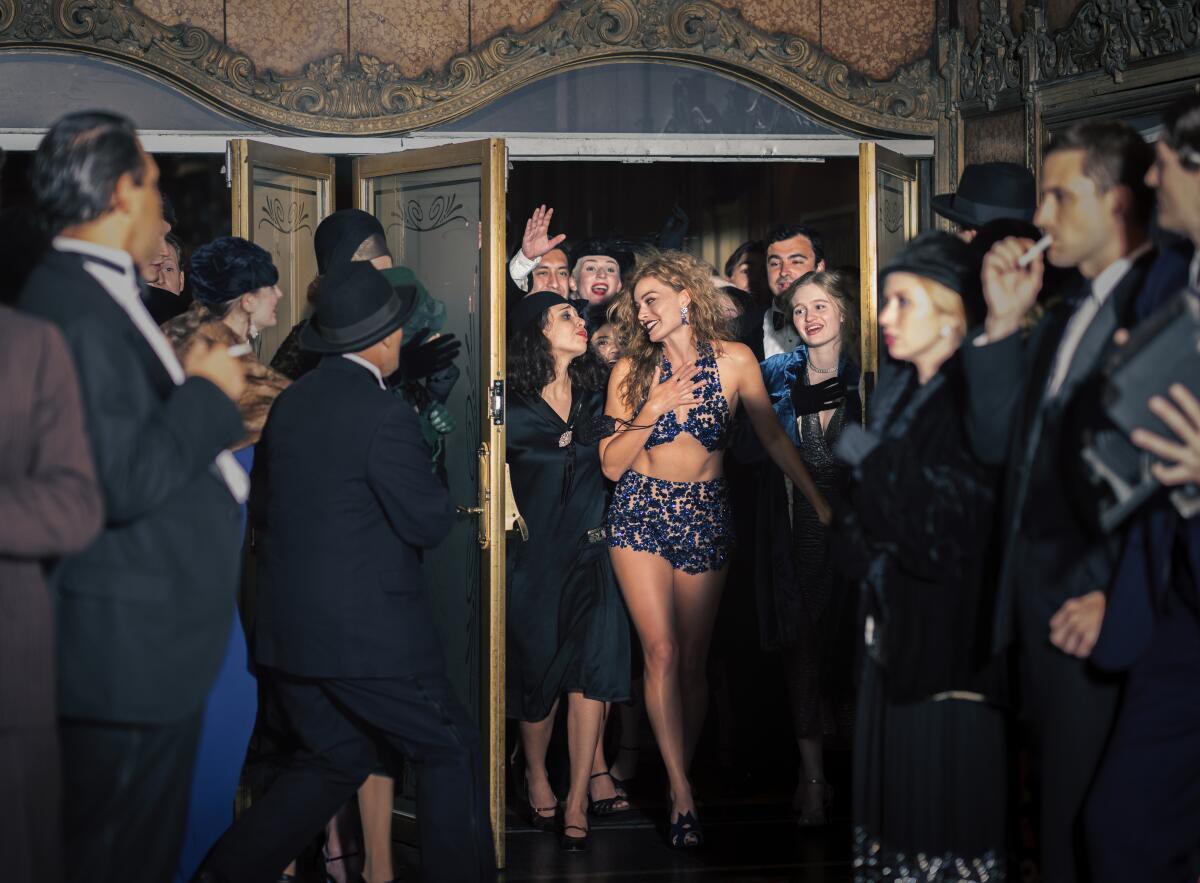

This upheaval forms the backdrop to Damien Chazelle’s delirious take on the period, “Babylon,” which follows a handful of characters attempting to navigate the tricky transition that snuffed out some of Hollywood’s hottest careers and revolutionized the industry.

Brad Pitt plays Jack Conrad, an alcoholic, womanizing leading man loosely based on John Gilbert, among other actors from that era. Conrad embraces sound as essential to the art form to which he has dedicated his life. Ironically, it does him in.

Margot Robbie’s character, Nellie LaRoy, is a gifted flapper who takes Hollywood by storm. Like Clara Bow, a vivacious young star who built her reputation playing the bad girl, Nellie struggles to stay relevant as the 1920s give way to a decade of Depression, war and uncertainty.

To measure the era’s fact against fiction, The Times spoke with “Babylon” director Chazelle, producer Matthew Plouffe and film scholars Annette Insdorf from Columbia University and Jonathan Kuntz from the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. Here are their insights.

Sound eclipses image

From the early days through the 1920s, the motion picture camera went from being stationary, approximating the audience’s point of view, to wandering freely in movies like Abel Gance’s “Napoleon,” King Vidor’s “The Crowd” and 1927 Oscar winner “Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans” by F.W. Murnau. The silent camera was hand-cranked, light and relatively quiet. Capturing sound, however, required cameras with noisy motors and muffling “blimps” around their bodies, making them unwieldy and relegating them to their former, static positioning.

“The advent of talkies undercut the rich image as the source of meaning. In addition, street scenes almost disappeared for about 20 years,” Insdorf said. “They returned when lighter camera equipment was developed in the 1940s, with films like Billy Wilder’s ‘Lost Weekend’ and Jules Dassin’s ‘The Naked City.’”

In fact, cameras were on the move again by 1932. Microphones were hung from mobile booms above the actors, and sound mixing techniques grew more sophisticated, freeing up filmmakers.

Brad Pitt, Margot Robbie and Diego Calva star in Damien Chazelle’s wild tour of the Dream Factory in its 1920s and ‘30s infancy.

Characters that fell out of fashion

Similar to John Gilbert, Pitt’s character sees his stardom vaporize in a few short years. Rumor has it that Gilbert, a leading man in the 1920s, had a high-pitched voice that couldn’t cut it in talkies. But that’s only rumor. More likely, studio honchos saw an opportunity to cut loose an actor with a fat contract when Gilbert’s movies began to stumble at the box office.

“His whole style and look didn’t work in the early ’30s,” Kuntz said of Gilbert’s suave, courtly manner. “It’s hard to maintain Hollywood stardom even without the transition to sound. They may have felt that the Clark Gable type — down-to-earth guys that spoke more in a snappy voice than John Gilbert — signified changing styles.”

Both Gilbert and Clara Bow, upon whom Robbie’s character is partially based, had personal issues that hindered their careers. Dubbed the “It” girl, Bow saw a meteoric rise and fall in the space of a few years.

“That moment where the bad girl went out of style is certainly part of what confronted Clara Bow and wound up screwing her ascent,” said Chazelle. “Once these changes were in the air, she became more and more aware of the parties she wasn’t being invited to anymore.”

Another factor was that Broadway came to Hollywood in 1930, bringing a new breed of actor, including the likes of Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart.

No love for Latin-sounding lovers

As depicted in “Babylon,” Hollywood was one of the most diverse communities in the country. Epitomized by Rudolph Valentino and Ramon Novarro, the Latin lover became a standard in the 1920s — but the archetype didn’t survive in the 1930s.

“Once sound comes in, so many of the Latino actors in Hollywood get funneled down to one or two people who can completely hide their accent and their heritage,” noted Chazelle.

Greta Garbo’s career accelerated despite her Swedish accent. She made her talkie debut in a now-classic adaptation of Eugene O’Neill’s “Anna Christie,” which was promoted under the tagline “Garbo Talks!”

Jafar Panahi’s “No Bears,” Todd Field’s “Tár” and Joanna Hogg’s “The Eternal Daughter” are among our critic’s favorite films of the year.

“Garbo successfully made the transition to sound in 1930, as did Ingrid Bergman nine years later,” said Insdorf, who suggested that a Scandinavian accent might have been easier for audiences to accept.

“The accent worked for her. It added to the mystique and mystery,” Chazelle said of Garbo. “But the number of actors they tried [to market with] ‘So and So Speaks!’ and it didn’t work far outweighs the occasional Garbos we remember who did make the transition.”

Wanted: Generic accents

If foreign accents were tolerated, regional accents were verboten. On film, Georgian Oliver Hardy did not speak like a Southerner, Dick Powell did not sound like a native Arkansan and Barbara Stanwyck hid her Brooklynese. All settled on a mid-Atlantic accent that characterized movie talk for decades.

“Back then they wanted to put up characters that were as generic as possible,” said Kuntz. “They tried to make everything as relatable to everybody as possible.”

A genre is born

Warner Bros.’ “The Jazz Singer” was the first movie musical, followed by MGM’s “Broadway Melody of 1929,” the first talkie to win an Oscar. Although the genre was sparked by the development of sound, it was touch-and-go for a while as films were shot with immobile cameras — a turn-off for audiences.

“By 1930, they’re pulling musical numbers out of movies and turning them into dramas because the public didn’t want to sit back and see it from a distance,” noted Kuntz.

It wasn’t until Busby Berkeley arrived on the scene in 1932 that musical numbers regained their dynamism through creative cutting and shot selection, rendering the genre a quintessential cinematic form.

Later revolutions

The closest modern Hollywood has come to a technological revolution on the scale of the shift to talkies was the introduction of digital cameras in the late 1990s. Not only did it force exhibitors to retool theaters — just as the advent of sound had done 70 years earlier — but by the early ’00s only a minority of productions were still shooting on film.

“I shoot on film. I like how it captures the light, the color range, the skin tones, especially shooting California light like in ‘LaLa Land’ and ‘Babylon,’” said Chazelle, joining A-listers like Christopher Nolan, Quentin Tarantino and Steven Spielberg who continue to rely on film stock. (Chazelle’s first movie, “Whiplash,” was shot on digital, however.)

Whitewashing or reclaiming? A new Whitney Houston biopic spotlights musical highs over personal lows

‘I Wanna Dance With Somebody’ is part of a broader effort to reframe Houston’s legacy in the years after her death.

“They’re sort of the Chaplin and Lillian Gish of the modern era, and they have a point,” said Kuntz, name-checking the most prominent silent-film holdouts. “There’s nothing like 35mm film. But it’s also commingled with the theatrical film experience going away. And losing that is significant. Once that goes, it’s not exactly the same Hollywood it was for 100 years.”

Is the sky still falling?

In the 20th century, some in the film industry feared that TV would kill the movies, yet they survived. Now, streaming services like Netflix appear to be drawing audiences away from the big-screen experience. But Chazelle isn’t among the doomsayers.

“If you look at the ‘50s, that was part of the subtext behind ‘Singing in the Rain’ being made — television threatening the moviegoing experience,” said Chazelle of the Gene Kelly classic, which plays a prominent part in “Babylon.” “I guess I remain an optimist that the core thing of people getting together in a dark room to communally experience a movie, that will continue to survive.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.