The greatest Mexican filmmaker you’ve never heard of

- Share via

Hollywood’s wholehearted embrace of Mexico’s Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro González Iñárritu and Guillermo del Toro has earned them enviable influential standing, five best directing Oscars in the last 10 years alone and a nickname — the Three Amigos.

Before getting there, however, who showed them the way? The hyper-successful trio has always acknowledged one particular living cinematic forebear with gratitude and admiration: an “imposing, mythical director,” Cuarón tells The Times, a “soldier of Mexican cinema,” per González Iñárritu. Says Del Toro, calling from Los Angeles, “He was incredibly kind to me when he didn’t need to be.”

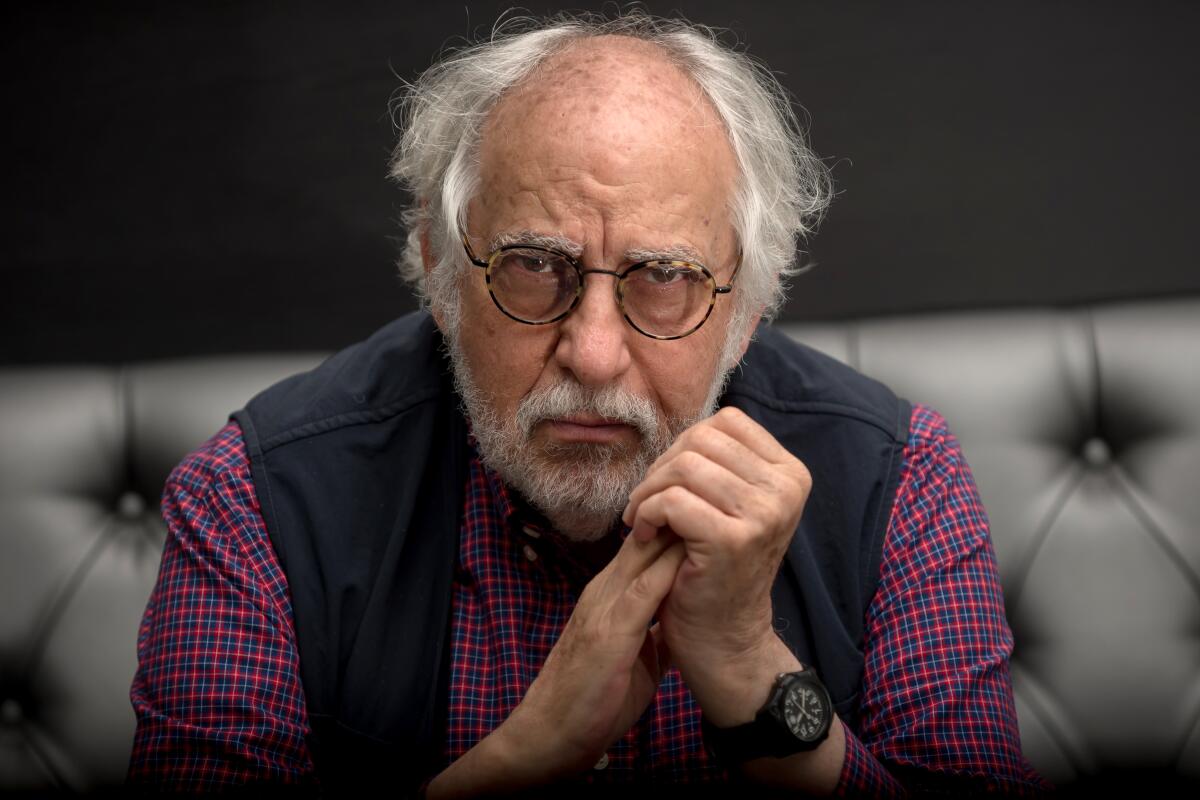

That man is Arturo Ripstein, one of the pillars of his nation’s independent moviemaking throughout the second half of the 20th century. Though he’s never found much acclaim on this side of the border, Ripstein occupies a vaunted status at home, entrenched between the sordid and the sublime. (Imagine a cross between Michael Haneke and Pedro Almodóvar.) Addictively, he evokes realms of unvarnished humanity, always steeped in morally objectionable behaviors and desires.

And now it’s our turn to catch up: This week, the American Cinematheque and the Hola Mexico Film Festival will co-host Ripstein and Paz Alicia Garciadiego, his longtime screenwriter and wife, in Los Angeles for a seven-day retrospective in honor of the director’s career (beginning Sept. 14 at the Aero Theatre and Los Feliz 3). It’s the first time the Mexican master will enjoy such a celebration in the entertainment capital of the world.

“As a young man I thought, ‘I’m very interested in two things: that my films are shown worldwide and to be able to live from my work,’” recalls Ripstein, 79, during a recent video call from Mexico City. “And that sort of thing happened in Hollywood. I wanted to try it out, but no one there was interested.”

Not unlike the tone of his films, there’s a biting humor in how Ripstein speaks about his long, mischievous run of work — especially what he sees as his own unfulfilled potential.

“I wanted to be Fellini or Kurosawa or Fritz Lang, but it didn’t happen,” he says, the smallest chip on his shoulder visible. “Luck chose for me to be Arturo Ripstein and I have resigned myself to being him all these years.”

In over 30 films since the 1960s, Ripstein’s lurid, ferocious heroes have included a pair of perverse killers (1996’s “Deep Crimson”), a trans prostitute running a brothel (1978’s “The Place Without Limits”) and a monstrous father keeping his family in captivity (1973’s “The Castle of Purity”). While others may judge these characters harshly, Ripstein centers them unabashedly.

“Art has to make the invisible visible, and that is enormously dangerous,” Ripstein says, “because one can live very calmly with the invisible.”

Bold in its depiction of horror and pleasure, his catalog brims with viciousness. “The universe of Ripstein and Garciadiego fearlessly delves into the swamps and darkness of the human soul,” González Iñárritu adds via email, describing their viewpoint as “paradoxically violent and nihilistic” while also being “compassionate and melancholic.”

The son of famous producer Alfredo Ripstein, a young Arturo had made up his mind about wanting to work in film. But it wasn’t until he watched Luis Buñuel’s savage 1959 satire “Nazarín” that he decided on his specific calling.

The 15-year-old Ripstein showed up at Buñuel’s office declaring he would become a director. The Spanish surrealist, a friend of Ripstein’s father, didn’t say much but showed him his classic “Un Chien Andalou,” and later let him hang around his sets. (Contrary to what Wikipedia says, Ripstein maintains he was never Buñuel’s assistant.)

“My dad didn’t want me to be a filmmaker — he was convinced that I was a bit of an idiot, and not without reason,” a candid Ripstein remembers. “Finally, through threats and fright, I convinced him to let me make a movie.” Ripstein cites his “contumacy,” a fancy synonym for stubbornness, as a decisive factor in maintaining an uninterrupted career for 60 years.

That first effort, 1966’s “Time to Die,” taught Ripstein, then 21, about the disappointments of his chosen profession. His father imposed a cast on him and demanded that the film be a Western, a profitable genre at the time. But it also ignited Ripstein’s lifelong creative bond with future Nobel Prize-winning author Gabriel García Márquez, then working in publicity, who co-wrote the screenplay with Carlos Fuentes, another award-winning novelist-to-be.

Cuarón remembers being astounded by “Time to Die,” about a gunman who serves time for murder and must now face the victim’s son. Already, says the “Gravity” and “Roma” director, Ripstein had “such a command of the language of cinema” and a potent interest in the darkest corners of human nature. “I once told Arturo that this was his best movie, which I don’t think he was happy about. But I still believe it’s a masterpiece about an inevitable tragedy.”

From then on, Ripstein favored working with novelists rather than professional screenwriters. And when he first collaborated with Garciadiego, a former children’s educator and TV writer, in the 1980s on “The Realm of Fortune,” he felt as though he’d finally found an ideal artistic ally. “The voice of my eyes,” he calls her.

Adapted from a story by lauded author Juan Rulfo, “The Realm of Fortune,” which centers on an impoverished man trying to jump-start his luck by entering the world of cockfighting, swept the Ariel Awards (the Mexican Oscars), nabbing nine trophies, including best director for Ripstein.

“The scripts Paz writes are very descriptive,” Ripstein says. “Completely different from the austerity that screenwriting teachers preach. Here, hyperbole and excess reign. Her scripts are novels with dialogue. They can be read not only as a work plan but as literature.”

Among Ripstein’s recurrent sources of inspiration, true crime holds a special place. His first box-office hit and still one of his best regarded films, 1973’s “The Castle of Purity” emerged directly from shocking 1959 headlines about Rafael Pérez Hernández, a man who, for 18 years, locked up his wife and children inside their home to save them from being contaminated by the filth of the outside world.

“I always liked the criminal cases in the newspaper, because they are narratively perfect,” Ripstein explains. “They are well structured, they have a beginning with motivations, they have a very clear development and, above all, they have a very precise ending.”

For both Cuarón and Iñárritu, “The Castle of Purity” was their initial encounter with Ripstein’s brutal world. “I don’t know if it’s my favorite of his, but it’s the one that most impressed me, because I first watched it as a child,” recalls Iñárritu. Similarly precocious, Cuarón was 12 years old when he saw it.

Another crime title, “Deep Crimson,” became Ripstein’s most acclaimed. The director and Garciadiego transposed the case of America’s infamous “Lonely Hearts Killers” Martha Beck and Raymond Fernández to a Mexican context for a richly textured noir about deadly passion. Recently restored to its original, longer cut and screened at last week’s Venice Film Festival, the updated version will have its U.S. premiere as part of this retrospective.

“His stories are universal,” says Del Toro, himself a shaper of dark fables that have connected with audiences globally. “He can take ‘Cyrano de Bergerac’ or ‘Romeo and Juliet’ and translate it to Mexico by just changing the specificity of the tale. That’s what he does. He’s very deliberate and very thoughtful about it.”

Sitting in front of his computer’s camera in a room overflowing with books, Ripstein invokes another true-crime enthusiast to explain his complex attraction to the blood-soaked genre.

“As Truman Capote used to say, ‘When God hands you a gift, he also hands you a whip,’” he says. “The gift for me was being able to film, and the punishment was having to see them. Seeing my movies has always been very difficult for me.”

Alongside the seductive beauty Ripstein derives from tragedy and misery, he also revels in Mexico’s colloquial language and popular culture with a panache that’s often poetic. Akin to the macabre lyricism of David Lynch’s moving dreams, Ripstein’s intoxicating frames feel otherworldly.

“My films are not politically, anthropologically nor sociologically valid,” Ripstein says. “They belong to a world that I have created for myself, within which there are rules, regulations, meaning and structure to everything.”

The director doesn’t see the evil that populates his scenes as uniquely Mexican but simply his interpretation of the only place he’s ever known.

“Our country understands that tenderness and cruelty sometimes come hand in hand,” says Del Toro, recently an Oscar winner for his Fascist-inflected animated “Pinocchio.” “That is very much part of Arturo’s own identity as a storyteller. People unfamiliar with his films are going to be surprised by their sophistication and precise tone.”

Ripstein recognized Del Toro’s talent early on and would read his screenplays and watch early cuts of his projects. “He was one of the mentors I was lucky enough to have as a young filmmaker,” Del Toro says, offering Ripstein as an example of a bridge between multiple generations of Mexican up-and-comers.

González Iñárritu agrees, describing Ripstein as a beacon. “His voice and vision of Mexicanness is persistent, unique and unmistakable,” says the “Birdman” and “Bardo” director. Cuarón, too, is convinced. “He’s fundamental in the history of Mexican cinema,” he says, “a master and a role model for all of us who came after. We owe him so much.”

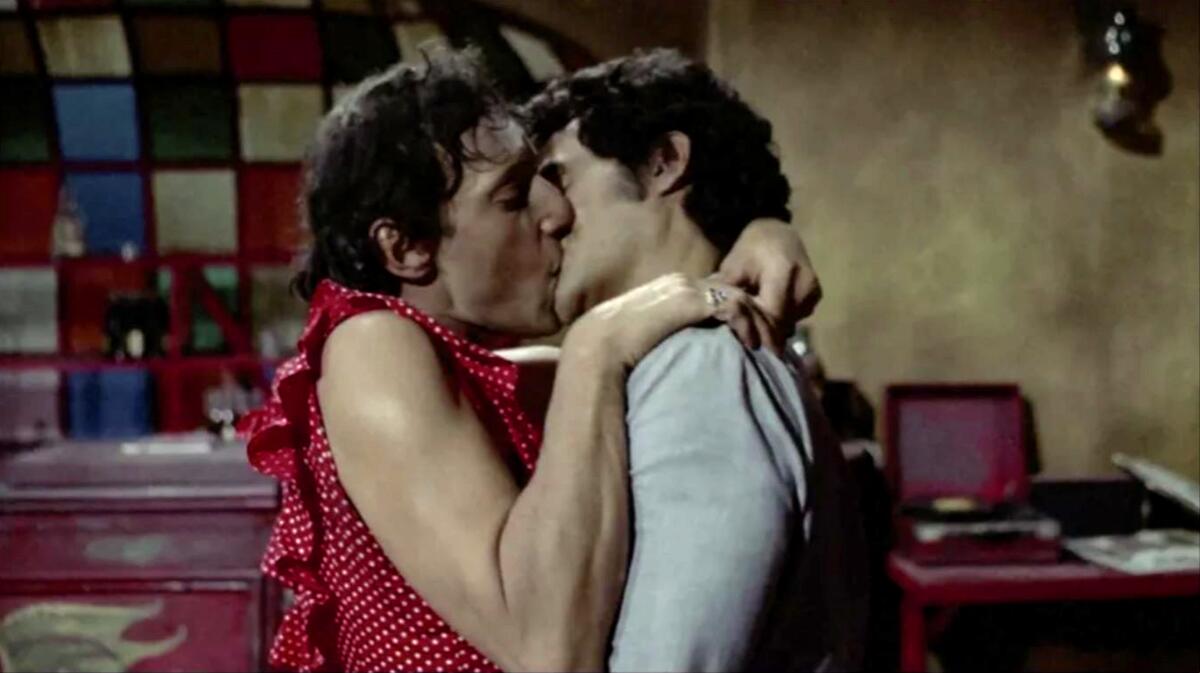

While his movies are decidedly not paragons of virtue, occasionally they’ve spurred social change at home. Ripstein’s “The Place Without Limits,” an adaptation of the controversial novel by Chilean author José Donoso, tacitly challenged ingrained Mexican notions of machismo in its portrayal of a gender-fluid sex worker, La Manuela (Roberto Cobo). The trailblazing film featured the first gay kiss in the history of Mexican cinema.

“It is the first film where homosexuality in Mexico was treated seriously and rigorously,” Ripstein says of his own film, not boastfully but with an earnest appreciation for its relevance. “The first Pride parade in Mexico was called ‘Mexico, Place Without Limits.’ To this day the film continues to have an impact in the LGBT community, and I am very pleased.” (Another of his movies, 1974’s “The Holy Inquisition,” remains groundbreaking as a chronicle of Mexican antisemitism during the Spanish Inquisition; Ripstein is Jewish.)

Far from resting on old triumphs, Ripstein has remained active in the new millennium. His latest bleak delight, 2019’s “Devil Between the Legs,” which explores an elderly couple’s warped sexuality, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.

“He has achieved a great longevity, despite the obstacles that it entails to make films in Mexico,” Cuarón says. “He underwent the cruelest eras for film production in the country but persevered.”

Ripstein’s provocations are still plenty shocking today. A notable festival that he won’t name rejected “Devil,” finding it off-putting. “They said it was ‘very disturbing,’” Ripstein says, mockingly shifting to English for the verdict. Facing an increasingly challenging economic landscape and the scorn of the morally righteous, he’s unsure of what’s next.

“I have no idea if this is the last movie I’m going to make,” Ripstein says. “I’m not planning to retire. I plan to find something that motivates me enough to fight like crazy to make it.”

The closest he came to his boyhood Hollywood dreams was when he directed 1976’s “Foxtrot,” an English-language drama shot in Mexico starring Peter O’Toole and Max von Sydow. That “terrible experience,” as he calls it, nearly prompted him to quit filmmaking for good.

Fortunately, a raging confidence kept him from capitulating. Now settled into his hard-earned and sharp-edged wisdom, Ripstein feels more audacious than ever.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.