For today’s confessional pop queens, Jack Antonoff is more than a producer: He’s a confidant

- Share via

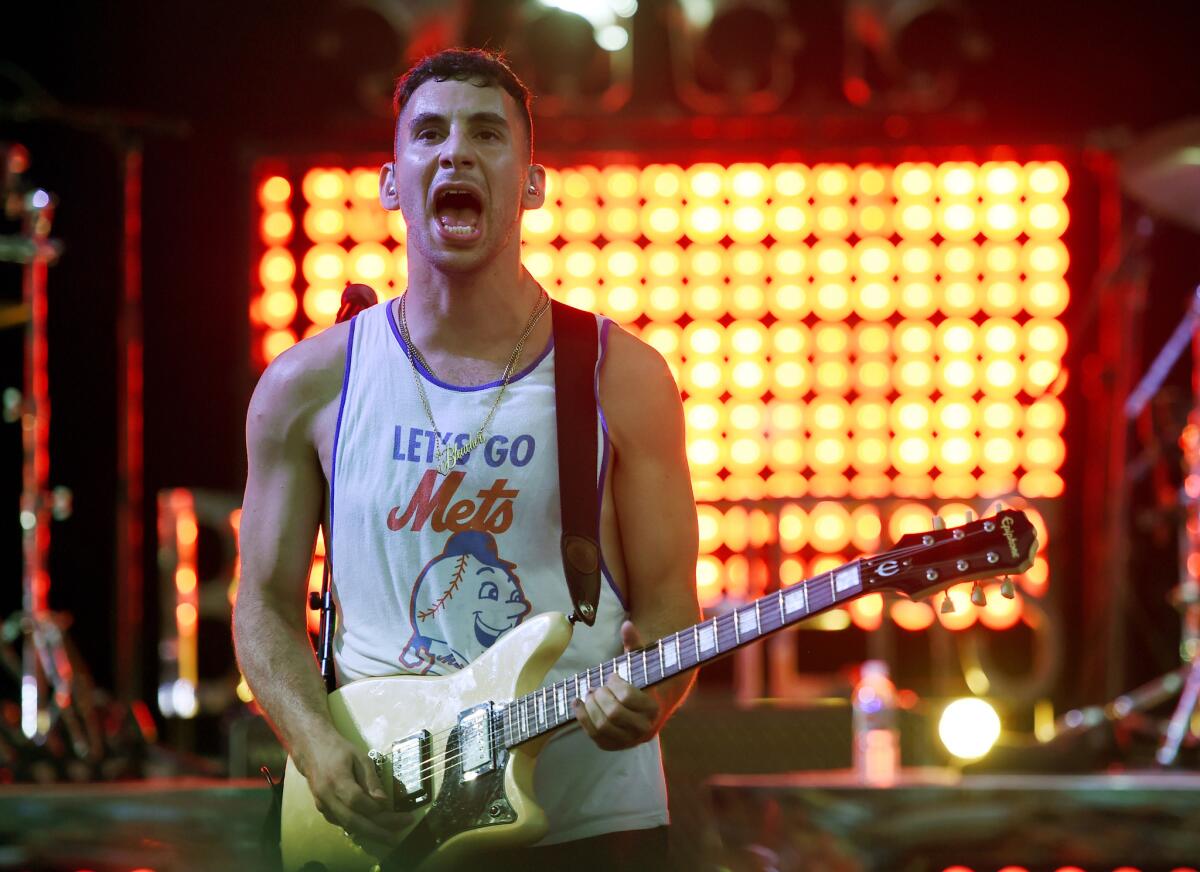

To meet producer Jack Antonoff behind the boards in the basement of Electric Lady Studios one Monday night in November, I first embark on a journey through time.

Descending the staircase of the legendary Greenwich Village studio founded by Jimi Hendrix in 1970, I hook a right past a blow-up of Patti Smith’s “Piss Factory” single, turn left at a rendering of David Bowie circa “Fame,” finally arriving at several walls filled with signed LP covers, from Smith’s iconic “Horses” to D’Angelo’s 2000 R&B landmark “Voodoo” to Frank Ocean’s 2016 epic “Blonde” — all recorded, in part, here. Electric Lady is saturated in myth. But song by song, Antonoff has written his way in.

Antonoff’s own records now line those hallowed Electric Lady walls, including Lorde’s 2017 pop opus “Melodrama,” St. Vincent’s sleek 2018 “Masseduction” and Lana Del Rey’s recent spectral masterpiece, “Norman F— Rockwell!” — he produced and co-wrote all three.

“I like to be looking at the North Star with someone, and we’re both trying to get there,” he says of his collaborations. “It’s a glimmer at first.... Every day we inch forward.”

Lana Del Rey on her love for the Eagles and all things California, her new boyfriend and the righteous anger of Greta Thunberg.

On Jan. 26, Antonoff and Del Rey‘s celestial compass will lead them to the 62nd Grammy Awards, where they’re nominated for album of the year for “Norman F— Rockwell!,” as well as song of the year for its title track. And for his work with Del Rey — plus Taylor Swift’s sharp “Lover” and albums by his trio, Red Hearse, and rapper Kevin Abstract — Antonoff, 35, has been nominated for producer of the year, non-classical. It was right here at Electric Lady that Antonoff produced the space-echo snare hits and reverby vocals of “Lover’s” dazzling title cut, with just Swift, Antonoff and engineer Laura Sisk in the room.

“When someone looks your way and says, ‘We see what you’re doing, and we see what you see in it’ — you feel encouraged,” Antonoff says of the nominations. “It’s not emotionally easy work.” The nods for Del Rey give him “hope”: “It’s proof that song of the year nominations aren’t just for No. 1 records.”

Antonoff’s rise began as a member of the rock band Fun., which took him on a whiplash roller coaster ride through mainstream music, winning two Grammys in 2013. He had already produced and co-written Swift’s heart-bursting “1989” highlights “Out of the Woods” and “I Wish You Would” when that group disbanded in 2015.

As a pop producer, Antonoff represents something of a new paradigm. Rather than stamping on a signature sound, he helps draw out an artist’s personality, often working on full-album projects in which Lana is her most dynamic Lana, or Lorde her most specifically Lorde. His signature, if he has one, is that the records he works on feature some of music’s most exacting lyricists and audacious personalities — students of Joni Mitchell and Bowie both — artists willing to sidestep pop formulas to arrive at, say, Lorde’s gloriously episodic “Green Light” or Del Rey’s nine-minute psych jam “Venice Bitch.”

In conversation, Antonoff endearingly dashes between ideas, occasionally taking to the stand-up piano or a 12-string guitar to illustrate how so many choices, both huge and microscopic, make up the work of production. Wearing a T-shirt for his cousin Jacqueline Novak’s off-Broadway show, “Get on Your Knees,” Antonoff slowly picks at a Sweetgreen bowl: “Ultimate metaphor for what’s wrong with our culture,” he says, referencing the salad and the exhausting nature of having limitless options. When not at Electric Lady, Antonoff works at his home-studio in Brooklyn Heights (an apartment he once shared with ex-partner Lena Dunham). He prefers to “hibernate” in New York over the churn of the L.A.-based songwriting system.

“I personally gravitate towards some level of cutting the s— and saying it like it is,” he says of his own songwriting style. “I just love when I’m being spoken to in a very unafraid way. I push myself to do that, so it’s easy to push others to do that.” He describes writing songs for other people as “a bizarre concept.” He’s more likely to mention the Beatles, Bowie, Mitchell, Kate Bush or Fleetwood Mac than anything contemporary. He calls live music “church” and is writing a book about CDs, called “Record Store.”

Antonoff’s personal relationship to music has, through his life, been an introspective one, “in my bedroom, headphones on, listening to things where I was in a deep conversation — just me and the album.” Almost every record he has been involved with this decade contains a song about crying, or feeling emotional, in the back of a taxi. He says he’s not responsible for all of them. “But I am very focused on the back seat as a metaphorical place,” he says, having grown up amid the driving culture of his native New Jersey.

The process of production, in Antonoff’s view, is akin to “holding a song in the best way.” “Production isn’t someone with the coolest snare sound. Production is the idea,” he says. “If you think about the most valuable thing in your home, and you were going to take it on a road trip, you wouldn’t throw it in a plastic bag and throw the bag in the trunk. You think of a song as the most special thing in the world, and then the production holds it or it doesn’t. And if it doesn’t, it’s horrible. It’s like seeing your greatest family heirloom in a bag in a dumpster. If it does, it’s beautiful, and it’s protected.”

Antonoff encourages his collaborators to express themselves as they would to a friend, in conversation. “I’ll be, like, ‘What about that thing you just told me about? What about that whole psychotic experience that so-and-so put you through?’” He calls it “a miracle” to find compatible writing partners. “Writing’s a very private thing, and when you can do it with someone else, it makes you feel like your private world is alive — much like when you meet someone, and they like the one bizarre thing that you like that no one else likes,” he says.

He felt just that way at the beginning of his work with Del Rey. In their first five hours of writing together, they finished two songs that would appear on the album: “Love Song” and the heartbreaking piano ballad “Hope Is a Dangerous Thing for a Woman Like Me to Have — but I Have It.” Much of the record was written with Antonoff and Del Rey sitting alone at the piano for hours recording onto their phones. “I would play stuff, and she would sing, and we’d talk about words,” Antonoff says. “There are these voice notes that go on forever. Lana would cut up the notes — she’s got this weird editing system — and she’d grab the pieces she liked.” Regarding one of Antonoff’s personal favorites, the end-times bar ballad “The Greatest,” he said, “The end just went on forever.… We were, like, ‘What if we just keep saying things?’”

But it was after tracking the Grammy-nominated title track that the album’s true power hit him. He calls the recording “super high-concept,” moving from “a little orchestra” to loose barroom piano playing, French horns, harps, tempo changes and diving and swinging until “this huge outro,” where “she would sing like a bird into the sky while the track melted.” Del Rey and Antonoff would play the song for trusted friends and family as “a statement piece of what the album could be.” “We were really proud of it,” Antonoff recalls. “We wouldn’t have been able to come up with some of it if there was too much attention put on what you can and can’t do.”

Antonoff came of age in the New Jersey punk scene of the late 1990s, a time he says still informs every decision he makes. He began touring as a teenager with his punk band, Outline, and, later, his indie-rock band Steel Train. “I’ve always been fueled by a feeling of being misunderstood,” he says. Seeing local bands such as Lifetime — whose singer, Ari Katz, Antonoff calls “one of the most important people to me” — made him think about the significance of community, operating with ethics, and writing lyrics to live and die by. “That scene was a crash course in how to reach people,” he says. “Everyone was dead-serious about everything. It really dared you to be there for the right reasons. Things can be real; things can be inspiring. It doesn’t all have to be a f— chicken nugget. It can be of substance.”

He grew up with an older sister, fashion designer Rachel Antonoff, and a younger sister, Sarah, who died of cancer when he was 18. He has processed grief and depression in songs under his solo moniker, Bleachers, such as “Everybody Lost Somebody” and “I Wanna Get Better.” “I do a lot of what I call living in tribute,” he says. “I think a lot about people who aren’t here. They are seeing what you do when no one else sees it.”

In producing, he refers to what Bruce Springsteen has called “frontier work,” meaning “unless you’re really out there,” Antonoff says, ”with no idea what’s in front of you, then don’t to it. And I’ve never made an album without a large part of me thinking: ‘Well, here goes.’” He believes his “frontier work” now is playing instruments in the room, making sounds that could never be made again. That includes, then, his in-process third Bleachers LP, and the album he’s just finished making with the Dixie Chicks.

Antonoff prefers to sit slightly left of what is most dominant in popular culture. “If you’re in the position to write and produce songs,” he asks, “shouldn’t your job be to do something so outside of the culture that the culture would follow you?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.