‘A grinding halt’: Record stores struggle to stay afloat amid coronavirus crisis

- Share via

The city permit that Amoeba Music had been anticipating came on March 18: After a years-long search to finally lock in a new L.A. home after selling its 31,000-square-foot Sunset Boulevard location to a developer, the city’s Department of Building and Safety approved construction applications for a new space a few blocks away at the corner of Hollywood and Argyle.

Little could Amoeba have known when its owners submitted the paperwork that a pandemic of Slayer-esque proportions would prompt the company, which as the country’s largest independent record store employs about 400 workers across its three California locations, to close the same day it got the go-ahead to start work.

For the record:

5:17 p.m. March 27, 2020An earlier version of this story said that Amoeba was still paying salaried employees. It is currently unable to pay either salaried or hourly workers.

“What would have been a moment of celebration,” Amoeba Music co-owner Jim Henderson says, “was just a further entrenched moment of, ‘Now what?’”

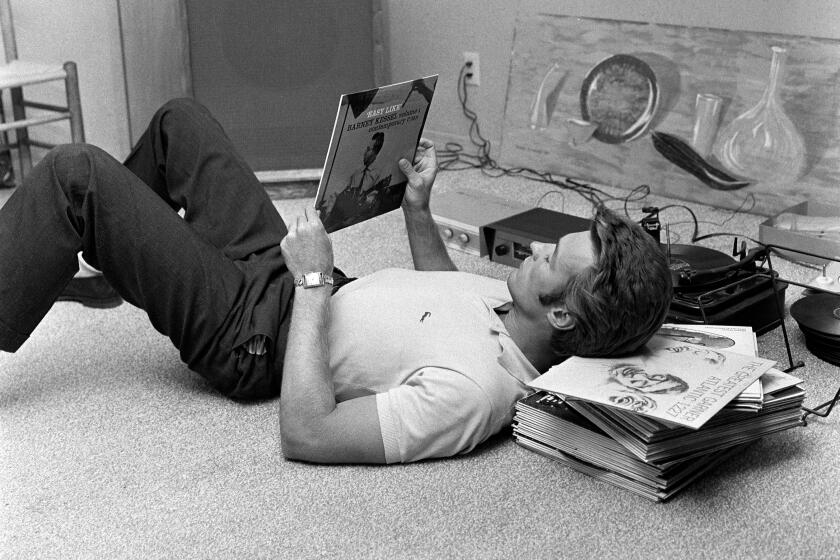

How to keep Coronavirus stress at bay: Listen, really listen, to your favorite albums, front to back, without distraction.

Across Los Angeles and the country, similarly baffled music retailers await word of how the $2-trillion relief package approved by Congress will aid their plight. In the short term, prospects seem dim. Record retail’s most profitable day, April’s annual Record Store Day initiative, has been postponed.

Nationwide, more than 120 independent shops have temporarily shuttered, according to Billboard, either out of caution or government-dictated stay-at-home orders. Profitable mail order businesses either can’t or won’t ship from UPS or the post office. Those that can, like Amoeba, are doing so with an abundance of caution.

As with most independent retailers facing extended shutdowns, stores’ survival will depend on the size of savings accounts and the speed of, and access to, government relief.

A few miles northeast of Amoeba at the Permanent Records Roadhouse in Glassell Park, owner Lance Barresi had banked on the idea that relocating his vinyl store to a space that had a bar and liquor license, which he did at the end of 2019, would yield higher margins.

COVID-19 has exploded that notion, Barresi says. “The beauty of the Roadhouse is that it’s a bar and a record store in one. The bummer of it is when the city — for the first time ever — tells all bars to close, see you later record store inside that bar.” He shut down his businesses on March 16, out of concern for both his customers and his employees. Walk-in traffic had slowed, he said.

Plus, he noticed that the shoppers who were still coming were shockingly under-informed, diminishing his ability to protect his clerks and customers. “If you’re sitting in a retail environment by yourself most of the day and the only people that are coming in are the ones who don’t recognize the severity of the situation, that makes things that much scarier for you as the person behind the counter,” he says.

Music retailers know from adversity, and those that have survived previous crashes can be an industrious bunch. Even before the pandemic, the business of selling physical product was enduring a series of debilitating setbacks. Virtually ignored by major labels that are now all-in on the music streaming model, record retail is a low-margin business that lives and dies on access to new and used product.

In 2019, a wrench in the supply chain caused by a reliance on overtaxed Indiana-based distributor Direct Shot led to release-day chaos and hindered the ability of retailers to restock in-demand titles. Earlier this year, a fire destroyed the Inland Empire plant of Apollo Masters, which long dominated the market for lacquer masters crucial for most U.S. vinyl pressing plants. How that loss will affect the ability of artists to press new vinyl records remains to be seen.

Despite the losses, physical music sales, which are the lifeblood of most indie shops, remained strong in the pre-COVID-19 era, says Eric Levin, president of the Alliance of Independent Media Stores, co-founder of Record Store Day and owner of Atlanta-based Criminal Records.

“We were doing fine. We were up 30% in early 2020,” he says. Most other stores in the 28-member alliance group were also thriving, Levin said.

In 2019, U.S. sales of vinyl rose by 14.5%, part of a 14-year ascent, according to the Recording Industry Assn. of America. Still, the format accounted for just 4% of U.S. music sales, compared with 82% for streaming. In 2019, 18.8 million new LPs and 46.5 million CDs were sold. By comparison, more than 1 trillion songs were streamed.

The latest updates from our reporters in California and around the world

Those numbers, however, don’t account for used-album sales. More profitable than new product, used media is the lifeblood of Amoeba, Permanent, Freakbeat in Sherman Oaks, Gimme Gimme in Northeast L.A., Fingerprints in Long Beach and the dozens of other shops in the region. But with no used music coming in and no physical store to sell what they’ve got, shops are scrambling to find new routes to profitability.

“I feel like I’ve got nothing to do and a ton to do,” says Dan Cook, Gimme Gimme‘s owner, adding that he feels “a little directionless.” Cook, whose shop was regularly featured in Marc Maron’s TV show “Maron,” has been trying to earn income by listing his stock in online marketplaces and highlighting choice titles on Instagram.

Freakbeat Records’ Bob Say says via email that the store is “managing to keep the mail-order going. It isn’t close to our usual business but helps pay the employees and rent. Everyone is involved in some aspect from home; making new listings, social media exposure, packing and shipping.

“Hopefully we can hang on through May,” Say concluded.

Vinyl buyers are a notoriously demanding lot who expect Amazon Prime-level service regardless of pandemic or pestilence, but Gimme Gimme’s Cook is not even sure he should be going to the post office. At Amoeba, Henderson says online sales have shot up, but the store’s ability to manage the influx has diminished out of concern for employees’ health and social distancing requirements.

Used records can’t be replenished with a call to a distributor. Many of the better shops fill their racks with vinyl purchased at one of the many massive annual record markets where professional crate diggers from around the world gather, says Permanent’s Barresi. Such convergences can now lead to mass outbreaks.

“Not only has our business come to a grinding halt, but all of our scheduled spring record-buying trips to record fairs across the country and internationally have been canceled,” Barresi says, listing markets at the Rose Bowl and Pasadena Community College and record fairs in New York and Austin, Texas. The world’s largest event, the twice-yearly Utrecht Record Fair in the Netherlands, also has been canceled.

Says Barresi with a resigned sigh: “A significant portion of our stock comes from sources that are completely unavailable to us at this point.”

With little income, stores are having to make hard choices. Amoeba’s Henderson says that the company is unable to pay its 200 salaried employees and has no work for its hourly clerks. Gimme Gimme, says owner Cook, is mostly a one-man operation, but he is continuing to pay his small staff. Permanent’s staff is hourly, but Barresi says he can afford to pay only a few employees right now.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security [CARES] Act does address the needs of small businesses such as Amoeba. Companies with fewer than 500 employees can apply for small-business loans, and money deployed for payroll will be forgiven if used within two months. It also includes aid for rent, mortgage and utilities.

On the other side of the country at Criminal Records, Levin recalls “feeling neutered” by the COVID-19 invasion: “My staff are record store warriors, and they were really trying,” he says of early efforts to remain viable amid the surreal situation. “When they weren’t doing curbside delivery, they were doing projects and cleaning and painting bins.” But soon fear seeped in. “One by one, they were like, ‘You know, I can’t come in.’” From a moral perspective, Levin had no interest in making demands, so he eventually shuttered mail-order operations.

He made the decision at the same time that the board of music retailers that plans Record Store Day announced the postponement of the annual event, originally slated for April 18. Levin says that “in the naivety of three weeks ago,” he was among those on the board successfully advocating it move to June 20.

Asked whether he thought that new date is realistic, Levin pauses. Stressing that he doesn’t speak for the board that will ultimately make the call, he says, “I wouldn’t be surprised if it moved. I would be surprised if it stayed.”

If the sector’s biggest day of sales is postponed once again, record stores will, again, lose a crucial payday at the worst possible time.

The financial hit is one thing, says Amoeba’s Henderson, “but there’s also the emotional one. In the L.A. store alone, we have over 30 people who have worked with us since Day One,” he says. “The relationships are really entrenched. We know these people. We know their children and their spouses and significant others. It’s familial.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.