L.A. jazz-soul legend Roy Ayers has a new album, and new hope for the future

- Share via

It’s an opening lyric so universal, tucked in a groove so essential, that the song seems to glow as it beams from the speakers.

My life, my life, my life, my life in the sunshine

Everybody loves the sunshine.

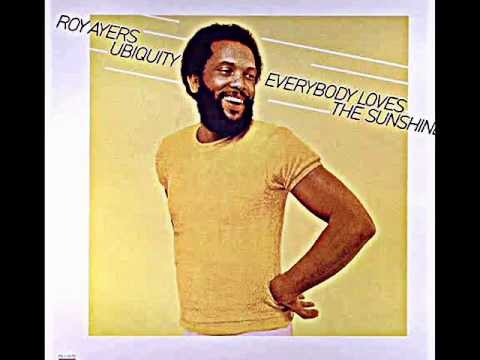

Written and performed by bandleader and vibraphonist Roy Ayers, who was born and raised on Vernon Avenue just south of downtown Los Angeles, “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” has become a Southern California anthem since its release in 1976.

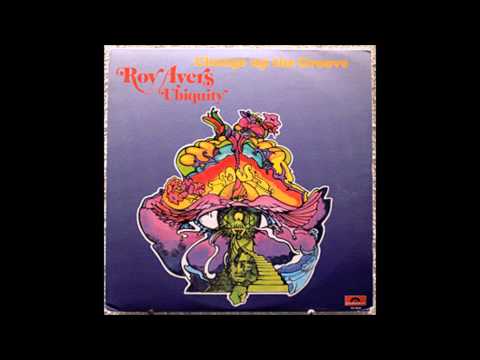

A minor hit when first issued, the jazz-driven soul song peaked at No. 51 on the Billboard charts. Its longevity is due in large part to its use in hip-hop and soul tracks. Snippets of the song have been sampled by Dr. Dre, Mary J. Blige, J. Dilla, 2Pac, J. Cole and dozens of others. Hundreds of other artists including Tyler, the Creator, Jill Scott and Madlib have sampled Ayers, earning him a vaunted place among music producers and DJs. His work in the 1970s leading six-piece band Roy Ayers Ubiquity helped spawn the subgenre called acid jazz.

Now in the twilight of his career, Ayers, 79, has just released a soul-funk album, “Roy Ayers JID002,” drawing on ideas from his prime “… Sunshine” era. A deeply relevant set captured to tape in conjunction with the 2019 “Jazz Is Dead” live series in a Highland Park nightclub, the eight songs were co-written and performed by Ayers with producer-composers Adrian Younge and Ali Shaheed Muhammad (A Tribe Called Quest) at Younge’s Linear Labs studio on Figueroa Boulevard.

Beyoncé, Drake, Lil Baby and Megan Thee Stallion are among the artists with tunes contending to be 2020’s song of summer.

During a recent phone conversation from his home in New York City, Ayers said that Younge and Muhammad approached him about recording in the midst of a series of gigs in February 2019. “When they reached out, I was very grateful,” he said. Shortly after the interview began, however, Ayers seemed to forget which recording he was discussing.

Standing by his side, Ayers’ daughter and manager, Ayana Ayers, apologized for what she called “a bit of confusion going on right now” and requested that the interview be rescheduled. She explained later, “My father is a few months shy of turning 80 years old and with that brings physical and mental challenges that all people experience when they reach his age.” Roy finished the rest of the interview via email.

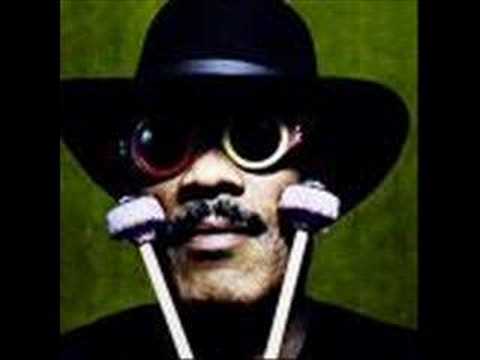

Last year at the Lodge Room in Highland Park, Ayers’ vibraphone playing was assured and confident. In front of a hometown crowd, during four sold-out sets over two evenings, Ayers stood center-stage, knit scarf wrapped on his head as a cap and a pair of mallets in each hand, tapping the keys of his instrument and leading a band through a set of expansive, highly percussive jazz-funk. Younge and Muhammad were part of that performance, and ahead of time they’d invited the New York-based Ayers to record at Linear Labs.

The session and gigs were part of a project called “Jazz Is Dead,” which in early 2020 dropped its first collection. It teased the Ayers album and forthcoming new work from other veteran jazz, soul and Latin artists: saxophonist Gary Bartz, keyboardist Lonnie Liston Smith, Brazilian jazz-funk band Azymuth, multi-instrumentalist and Gil Scott-Heron collaborator Brian Jackson, bossa nova outlier Joao Donato, singer and songwriter Marcos Valle and saxophonist Doug Carn. Younge and Muhammad’s own band, the Midnight Hour, rounded out the compilation.

Ayers hadn’t issued a full-length album in nearly a decade. In the interim, his legacy had only grown.

Born and raised on East Vernon a few blocks from the then-thriving Central Avenue jazz and R&B scene, Ayers started playing music in the mid-1940s and earned his earliest credits as part of the city’s cool jazz movement. His 1963 debut solo album, “West Coast Vibes,” was produced by the late Downbeat editor and Times jazz critic Leonard Feather, and across the 1960s Ayers released a series of albums for labels including Pacific Jazz and Atlantic.

He moved to New York as funk music morphed into fusion in the early 1970s, formed Ubiquity and signed to Polydor Records. The nine studio albums Roy Ayers Ubiquity made from 1972-77 are considered his most crucial work.

“We used to see the sun disappear,” Ayers told an interviewer in 2013 of the inspiration for “Everybody Loves the Sunshine,” adding that “the smog and the fog would come through the Los Angeles basin. You couldn’t believe it. It was horrible.”

With a spirit that could interrupt even the darkest days, the song’s optimism, and logic, was undeniable. Who could argue with a psalm for sunshine and a life filled with “just bees and things and flowers?”

“I wrote the song because I felt it,” Ayers explained via email when asked about its place in Southern California culture. “Perhaps because it is sunny and lovely out on the West Coast, that came through.”

Or perhaps it’s Ayers’ vibraphone tone, which across nearly 70 years of playing has become a pure, unimpeded extension of his voice. Both of his parents played instruments, and when he was little they took him to see jazz vibraphone player Lionel Hampton at the Paramount Theatre in Boyle Heights. During the concert, Hampton left the stage to interact with the crowd. “As he came past me, he handed me a pair of vibraphone mallets and I grabbed them,” Ayers recalled in 2014. “I was five-years-old, and my mother said he laid some spiritual vibes on me.”

Seventy-five years later, those vibes remain. Asked about his legacy, Ayers replied, “I’d like it to be that I was one of the greatest vibists that ever lived. A person who could and did inspire others, and was highly respected in this crazy world of music and artistry.”

He needn’t worry. It’s the reason Younge and Muhammad, who earned acclaim for their collaborative scores for Marvel’s “Luke Cage” series, entered the studio with him in winter 2019. Describing it as “a dream of ours to be able to work with the greats and continue the conversations that they started years ago,” Younge called the Ayers record “essentially an extension of his legacy, and us paying homage to him and us learning from his music.” Joining in for the session were veteran trombonist Phil Ranelin and tenor saxophonist Wendell Harrison, both of whom issued records for the noted L.A. jazz imprint Tribe Records and will be the focus of an upcoming Jazz is Dead full-length.

“We’re all older, and a lot of these icons are still alive and well,” Younge said, adding that the project “serves as a way to work with these artists in a new light.”

The studio sessions and the live sets, coordinated with “Jazz Is Dead” co-curator Andrew Lojero, were designed to celebrate legacies of artists while they’re still able to play.

“In the culture of music, a lot of times we don’t go back to work with the icons who inspired us,” Younge says. “Something that’s very integrated into Black culture is that once we finish something, we leave. It’s not one of our best attributes.” He adds, “We need to always preserve our legacies, in the tradition of other cultures.”

One exception, Younge notes, has been hip-hop producers and the devoted fans who reverse-engineer tracks. “When you’re sampling certain records and then going back to the original records, you are now studying artists you never would have discovered. Now, you not only like hip-hop, but you like the country songs that they sampled. You like the psychedelic rock group they sampled. You like the jazz.”

For their entire lives, hip-hop “has been a conduit, a bridge to the past for us,” Younge says. “Now when we think about creating music, it’s as if we’re thinking about these samples in our head.”

In fact, Younge first learned about Ayers’ music through A Tribe Called Quest samples. “Me developing as a musician was based largely on a lot of the work that Ali was doing,” Younge said, adding that A Tribe Called Quest’s samples of Ayers, Bartz and others “helped to make them icons for the hip-hop generation.”

Most famously, A Tribe Called Quest tapped portions of Ayers’ ”Runnin’ Away” for its 1989 track “Description of a Fool,” and Roy Ayers Ubiquity’s 1974 song “Feel Like Makin’ Love” on “Keep It Rollin’,” from the hip-hop group’s classic 1993 album, “Midnight Marauders.”

Bars and breaks from songs on “Roy Ayers JID002” could just as easily be sampled in future work. Rich with a female chorus of vocalists expressing positivity and reveling in the power of music to, as the opening song describes it, “synchronize vibrations,” songs such as “Hey Lover” reconfigure the groove-heavy textures for 2020-accented romancing. “Solace” is a four-minute workout that finds Ayers maneuvering across his keys as though conversing in melodic paragraphs.

Closing song “African Sounds” features Younge reciting words, penned in part by Ayers, that celebrate “Black and brown, these African sounds.” It could have been written for the current Black Lives Matter protests, or at any point across the country’s history. “Without a choice, we have the choice to use our power through sound, to rebound against the hate,” Younge intones, in the hope of “seeing through the misty shades of America.”

The album concludes, “By choice and by force, we are colored by the African sun.”

Neither Younge nor Muhammad wanted to speak publicly about Ayers’ declining faculties. Muhammad did note that during the sessions, he came to understand that when recording Ayers, “you’re going to get the best of him in very short spurts of time.”

Asked how he thought the album turned out, Ayers replied concisely. “I thought it sounded smooth. Some nice grooves on this album for sure.”

Ayers, who will celebrate his 80th birthday in September, said that the protests following George Floyd’s killing at the hands of police give him hope for the world his children and grandchildren are inheriting. “I am optimistic,” he wrote, “for the first time in a long, long time.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.