In 1990, Rock the Vote and Madonna shook up politics. Will the youth vote do the same in 2020?

- Share via

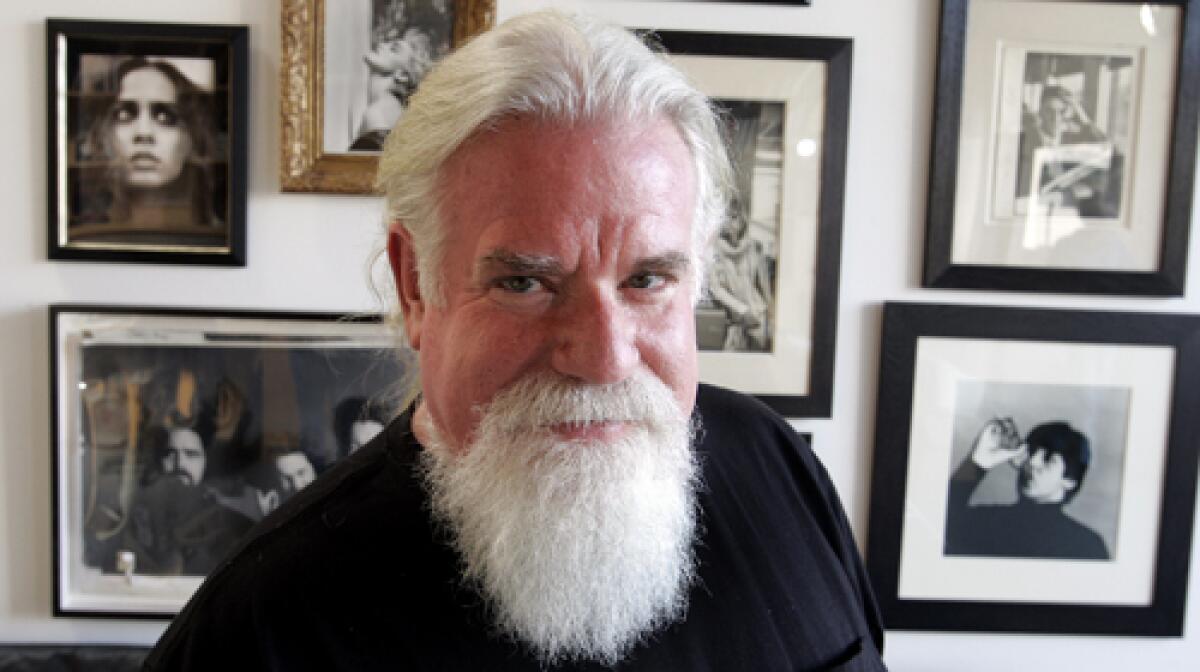

In 1990, music executive Jeff Ayeroff had been growing increasingly frustrated at the effort by Washington politicians to censor artists in his industry.

Then he decided to get even.

For the record:

11:59 a.m. Oct. 28, 2020An earlier version of this article said Rock the Vote was based in Baltimore. It is based in Washington, D.C.

Using MTV and the hottest pop star of the moment, Madonna, his vengeance had a lasting impact.

Ayeroff, 73, grew up in a politically active household where he watched images of the civil rights struggle in the South play out on his black-and-white TV set. When he saw that the Parents Music Resource Center, led by a group of political wives including Tipper Gore, had succeeded in getting record labels to affix parental warnings on albums that contained sexually explicit or violent lyrics, the playbook was all too familiar to him.

“It was always good fodder for politicians to take on rock ‘n’ roll because they knew kids were not a constituency,” he said in a recent phone conversation from his home in Los Angeles. “They didn’t vote enough to make a difference and you could scare their parents.”

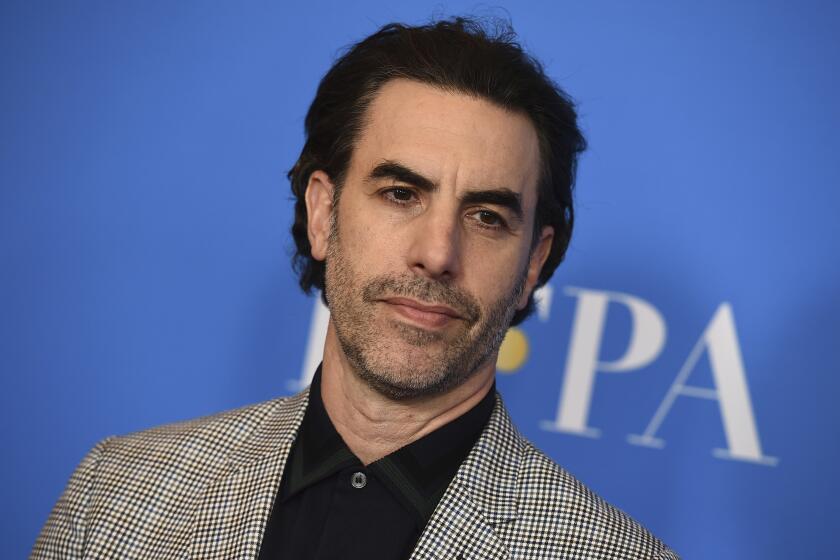

‘I’m always looking for people to play racist buffoons,’ Sacha Baron Cohen tweeted after Trump called him a ‘creep’ upon the new ‘Borat’ film’s release.

Instead of just lobbying lawmakers to protect the creative expression of his artists, Ayeroff went a major step further by forming a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to boosting voter registration and participation among young people — historically a group less likely to show up at the polls.

Ayeroff’s creation, Rock the Vote, has lasted three decades, evolving into a technology-driven resource that helps register first-time voters from underrepresented groups. Its current reach goes far beyond its days of wrangling Metallica or Michael Bolton fans to sign registration cards outside of arenas.

In 2018, the Washington-based organization helped facilitate 8 million voter registrations, according to its annual report. Turnout among voters under 30 for the midterm elections that year was the highest in 25 years.

But in the early 1990s, the emergence of Rock the Vote was the kind of game-changing collision of pop culture and politics that may no longer be achievable in today’s highly fragmented media landscape.

A music industry macher, Ayeroff had risen through the ranks as an art director and marketing executive at Warner Bros. and A&M to lead Virgin Records in the U.S. Along the way, he helped shepherd the careers of such artists as Madonna, Prince and the Police.

Ayeroff’s understanding of the visual iconography of rock acts made him well suited for the rise of music video and MTV, and he backed it up with lavish spending on the production of clips. It helped him forge a strong relationship with MTV, which at the time had a hold on the young adult audience like no other media outlet in the pre-internet era.

“I was a very popular customer,” Ayeroff recalled.

Ayeroff approached MTV executives with his idea of a voter registration and participation campaign driven by public service announcements using rock stars as advocates. He had the financial backing of the major record labels. Judy McGrath, creative vice president of the network at the time, fully embraced his pitch even though some people told her the cause was not a fit with the network’s rebellious brand. Voting was something that old people did.

“I thought it was an invitation to the powers that be to address a disengaged generation on their own terms,” McGrath said. “We were inviting them in and we were going to do it the way we did everything — with spirit and fun and creativity and music. Who the hell knew if it was going to really have an impact?”

‘Networks should do this once a week’ and other forward-looking thoughts on ‘Essential Heroes: A Momento Latino Event.’

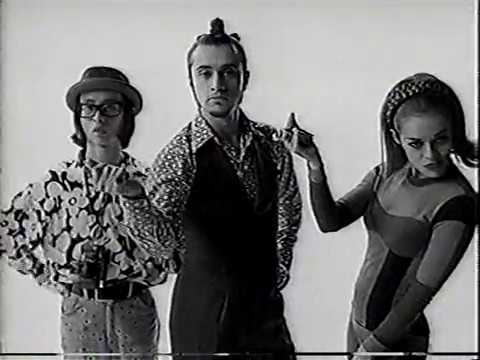

Ayeroff recruited Madonna, with whom he’d worked at Warner Bros., for the first Rock the Vote spot. She was at her multi-platinum apex with “Like a Prayer” still riding the charts. Paula Greif, who had worked on the graphic design of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” album, was asked to direct.

On the day of the shoot, Madonna and two of her dancers showed up at Greif’s apartment in Manhattan’s West Village with a large American flag. Performing in front of a white background, the superstar wrapped herself in Old Glory, wearing only a red bra and panties from Greif’s own lingerie drawer, and combat boots.

“She came in and she was really crabby,” Greif recalled. “She didn’t want to be there. She was doing it because Jeff Ayeroff told her to do it. But her crabbiness comes across in the whole thing and it really works.”

Madonna did not even attempt to offer the look-into-the-camera earnestness that celebrities typically delivered in public service announcements. Using the tune of her hit “Vogue,” she spouted lines written for her by style columnist Glenn O’Brien, such as “Dr. King, Malcolm X / Freedom of speech is as good as sex.”

Her dancers, dressed in denim cutoffs and white T-shirts, sang off-key in the background, creating a moment that was all at once playfully sexual, weird, intimate and spontaneous. She ended the 60-second performance, edited together from a small number of takes, with the guaranteed-to-outrage line: “And if you don’t vote, you’re going to get a spanky.”

(Greif suspects that a production assistant absconded with the now historic bra and panties from her apartment after the shoot.)

McGrath believed the spot had the authenticity needed to work for her young viewers. “If a kid didn’t realize the point of voting, there it was coming from their icon, doing it exactly her way, draped in a flag,” she said. “I thought, ‘This is so fantastic. I can’t wait to get it on, and I’m gonna get freaking killed for it.’”

Once the spot started airing, calls came in from the usual suspects who made noise whenever MTV stepped out onto the cultural ledge, such as the Catholic League and conservative Republican politicians. Touchy advertisers did not want their commercials running adjacent to the PSA. The Veterans of Foreign Wars turned it up to 11, accusing Madonna of desecrating the flag.

But more acts such as Lenny Kravitz, Deee-Lite and Megadeth signed on to promote Rock the Vote and the campaign became the bridge to McGrath’s ambitious plan to have MTV News cover the 1992 presidential election. She sent a young reporter, Tabitha Soren, to New Hampshire where a baby boomer-aged Arkansas governor named Bill Clinton was among seven Democratic candidates toiling for primary votes for the nomination to challenge the Republican incumbent, George H.W. Bush.

McGrath recalled how Clinton was the only candidate who recognized the MTV logo on Soren’s microphone flag and gave the reporter an interview. He later participated in a town hall-style forum, and the network’s political coverage — branded as “Choose or Lose” — was off and running. Clinton’s opponents and the rest of the grown-up establishment media were forced to pay attention.

Rock the Vote had scant impact in the 1990 midterm elections the year it was launched. But more celebrities lined up behind the effort in the 1992 presidential race, which saw a 12% increase in voter turnout among 18- to 24-year-olds. A veteran Hollywood political activist, Patrick Lippert, was hired to run the operation in 1991 and tied it to the effort to pass the National Voter Registration Act, which would enable people to register to vote at their local motor vehicle bureau.

McGrath made sure that Lippert, who was dying from AIDS at the time, got to meet Clinton at MTV’s inaugural ball. Clinton gave his assurance to Lippert that he would support what became known as the “Motor Voter Bill” and, as president, name-checked the organization at the signing ceremony.

“We had cultural clout,” said McGrath. “When you feel it that way, there is nothing like it.”

Rock the Vote continued to crank out celebrity-oriented campaigns in the election cycles that followed. But getting consistent growth in voter participation among young adults has remained challenging.

Ari Berman, author of “Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting in America,” said state laws are often an obstacle.

“In Ohio, Texas and Georgia, they’ll cut off registration on Oct. 5, and a lot of young people don’t even start paying attention to the election until after that,” Berman said. “Under the voter ID law in Texas, you can use a gun permit but not a student ID.”

With the emergence of social media, where celebrities can pontificate on any subject or cause on Twitter, TikTok or Instagram, a Rock the Vote-type testimonial does not have the attention-grabbing impact it once had.

But Rock the Vote was early in recognizing how young people were migrating away from traditional television and toward the internet. The organization built the first online voter registration platform in 1998.

While the splintering of the mass audiences television once reliably delivered has made the collective galvanizing experience of the early 1990s impossible to replicate, current Rock the Vote executive director Carolyn DeWitt believes technology has allowed the organization to reach potential new voters with greater efficiency.

“The organization has had to continuously adapt to stay relevant,” DeWitt said. “When Rock the Vote was founded you could make a PSA and it would reach 90% of young people. Fast-forward to today, you have the internet, you have apps, you have text messaging. There are just so many more platforms that both distract people and also provide an opportunity to reach them.”

The uprising in cities across the nation after the May 25 death of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis has further energized Rock the Vote’s efforts. In June, the organization signed up 50,000 new voters in a single week, its highest number of the year.

DeWitt said Rock the Vote’s technology platform is now used by more than a thousand voter registration organizations whose targets go well beyond young adults, including Head Count, Voto Latino, March for Our Lives and the NAACP. After the registration process, text messages and emails are sent to remind people about dates and deadlines related to national and local elections.

Rock the Vote no longer canvasses potential voters at events, but its on-the-ground efforts have included partnering with professional sports leagues on converting arenas and stadiums into polling sites for the 2020 election.

Data show the efforts have paid off. In Florida, a key battleground state in the 2020 White House race between President Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden, the early vote among adults aged 18 to 29 is three times the amount compared with 2016 at the same stage of the election, according to the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University.

Ayeroff remains on the board of Rock the Vote and is proud of how its ethos has spread over the years.

“Rock the Vote created the oxygen for so many youth voting organizations to grow,” he said. “The more kids vote, the better off the country is.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.