A complicated, groundbreaking punk heroine gets her due in new documentary

- Share via

The 12 near-perfect songs on “Germfree Adolescents,” the 1978 debut album by X-Ray Spex, clock in at just over a half hour, but the shock waves they detonated keep rippling out 44 years later.

One of the most brilliant albums to have emerged out of the turbulent cauldron of Margaret Thatcher’s England, “Germfree” is insightful in its critique of commercial culture and as infectious as any great pop album. And it doesn’t even include the band’s first single and most famous song: the feminist anthem “Oh Bondage Up Yours!,” a punch upside the patriarchy’s head delivered with a rebel trill by singer Poly Styrene.

Unfortunately “Germfree Adolescents” was also the only X-Ray Spex album, until they regrouped almost two decades later to record the underrated “Conscious Consumer.” The nihilism of the punk scene and the pressures of fame were too much for the gifted, groundbreaking frontwoman, the first person of color to front a punk band. She suffered a mental breakdown and joined the Hare Krishna religious sect a couple of years after “Germfree’s” release. X-Ray Spex inspired generations of future Riot Grrrls and Afro punks, but they might otherwise be largely forgotten if it weren’t for “Poly Styrene: I Am a Cliché,” a new documentary co-directed by someone who knew Poly better than anyone, for better and for worse: her only child, Celeste Bell.

“It’s an exploration of the relationship between mother and daughter,” says Bell, 40, of the film, which comes to American theaters on Wednesday. “That’s universal. Every daughter will relate to the challenges of that relationship, even if you don’t have a mother who was as unusual as mine.”

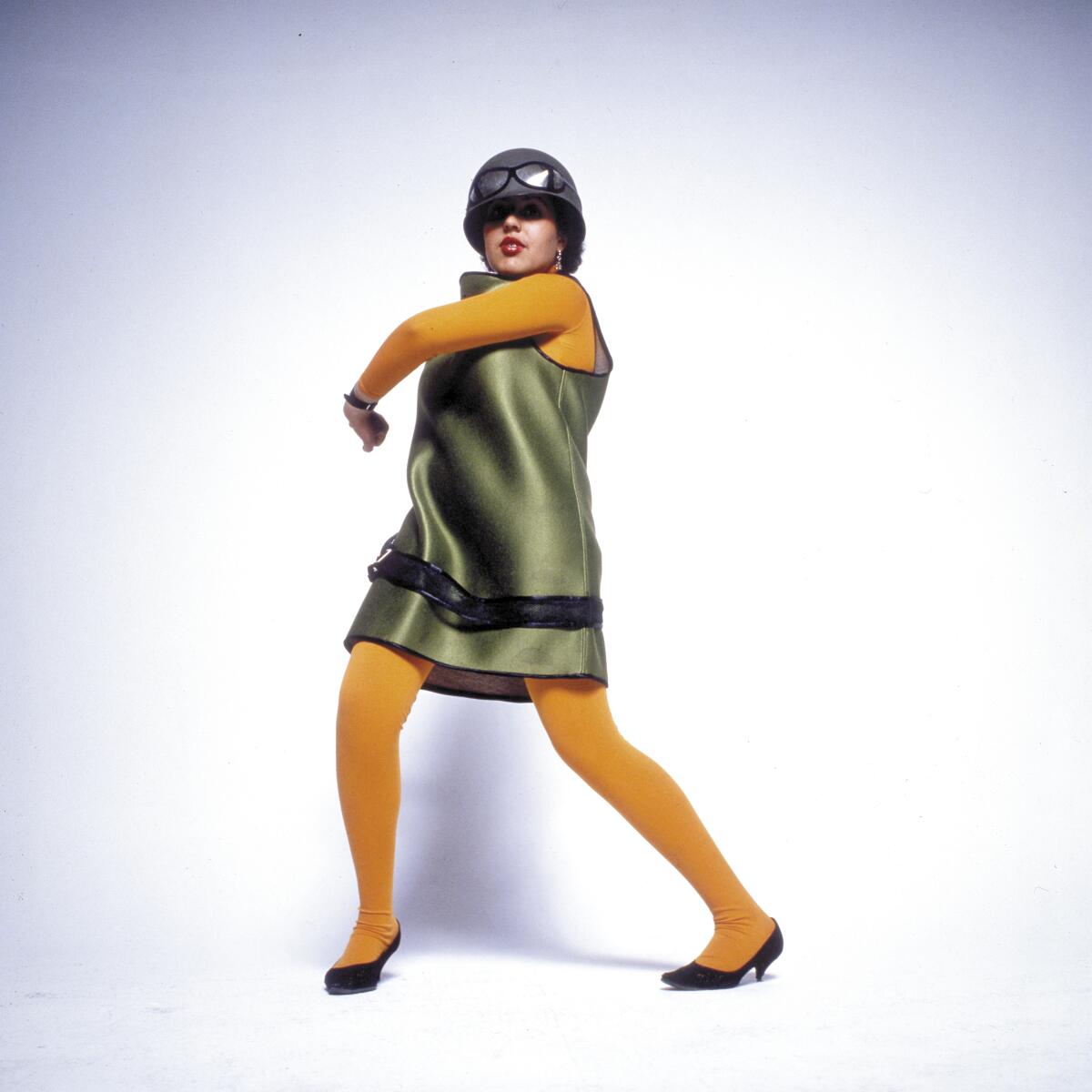

Unusual is an understatement, just as the film’s title is ironic: a cliché is the last thing Poly Styrene was. In a scene replete with colorful, inventive individuals, the woman born Marian Joan Elliott was truly unique. She designed her own outfits, was known to sport a helmet and wore braces on her teeth. True to the punk scene of late-’70s London, she sang in a broad cockney accent, but she also had pipes influenced by Aretha Franklin, and X-Ray Spex featured a saxophone player (originally another woman, Lora Logic). Styrene, who died in 2011 of cancer, wailed on songs about plastic culture and fake authenticity — or was it authentic fakeness? — with the brilliance of a critical theorist and the lyrical incision of a Cole Porter. She chanted the couplet cry of the insider outsider: “I am a poseur and I don’t care, I like to make people stare.”

Styrene’s brash articulation of the biracial art of code switching and her enraged, but also humorous, gender revolt is finding a new audience among today’s more socially conscious Gen Z. “In the masculine, majority white punk world of London in the late ’70s, Poly Styrene was a rare outlier,” says Stephanie Phillips, guitarist for the London-based band Big Joanie, one of the many contemporary acts that have taken up Styrene’s charge. “Through her prescient lyrics that focused on climate change and consumerism, her rebellious DayGlo attire and guttural operatic yell, Poly created a persona that has become the standard bearer for feminist punks everywhere.”

If you’re Team Neil and looking for an alternative to market-leader Spotify, there’s a wide variety of streaming services to match your music needs.

That persona is the driving force of “I Am a Cliché.” The film, which grew out of a book co-authored by Bell and the writer Zoe Howe, features previously unseen artifacts and footage including X-Ray Spex rehearsals in 16mm, fashion sketches by Styrene and writing from her diaries. Together they reveal the depth and complexity of the multitalented artist’s ideas at a young age: She was 19 when the band formed.

“The documentary really shows how engaged she was in every aspect of being an artist,” says Vivien Goldman, a journalist and musician who knew Styrene beginning in the late ’70s. “Everything was unique. And nothing was by chance. Just the spread of her work, seeing all her artwork and seeing her lyrics, handwritten — I hadn’t fully realized the care that went into the package, because it just seems so natural.”

Styrene had a Somalian father and a white English mother. She grew up in Brixton on a council estate (English public housing). She struggled in school, which she left at 15, and was largely self-taught.

“My mother told me that she had a sense from a very early age that she wasn’t like other children in the sense of how her brain works,” Bell says. “She found it very difficult to concentrate at school, it was almost impossible for her.”

Being biracial did not make life easier for Styrene. Paul Sng, who directed the film with Bell, says her background is part of what drew him to Poly.

“What connected me beyond loving the music was some similarities that I guess I share with Poly: We’re both mixed race, both working class, both grew up on a council estate,” the British Chinese filmmaker says. “The things that Poly experienced in terms of not fitting into one world with the white working class, and then not really being accepted by the black community: That was something that was similar to my experience. When you don’t really feel one thing or the other, you become an outsider. … Poly’s art and music is very much informed by that experience of being other, and not just being other but being othered.”

Styrene expressed this confused sense of self in “Identity” on “Germfree”: “When you look in the mirror / Do you see yourself / Do you see yourself / On the TV screen / Do you see yourself in the magazine / When you see yourself / Does it make you scream.”

Growing up, Styrene listened to rock ’n’ roll and R&B; she loved T. Rex, Motown, Roxy Music. Seeing the Sex Pistols inspired her to form a band. According to the film, she was obsessed with Pistols singer Johnny Rotten. Hanging out at his house one day with a group of other punk scenesters, Styrene felt the old feeling of not belonging. She disappeared upstairs and eventually came back down having shaved off all of her hair. Ironically, the biracial now-skinhead performed at a Rock Against Racism rally the next day.

Goldman remembers the incident well as an example of how toxic punk could be: “John had racist and sexist forces around him. And unfortunately, nobody defended her.”

At the same time as she was feeling isolated, Styrene was emerging as one of Britain’s most exciting new performers. “People don’t understand that in England, she was also a pop star,” Goldman says.

For middle-class artists like L.A.’s Best Coast, touring means everything, financially and spiritually. An inside look at what’s lost when the show can’t go on.

Being a pop star made Styrene even lonelier and more distraught. In one scene in the film, she’s trying to exit a stage and a man is all over her, stopping her, trying to kiss her, molesting her. She’s surrounded by white men pushing and shoving her. It’s incredibly difficult to watch, oh, so symbolic of the treatment of “the othered” in the music industry — and not just a symbol, but Styrene’s lived reality.

“One of the things that we covered in the film is the lack of protection that Poly had,” says Sng. “There was no one around her who was able to put an arm around her and stop people like that from getting to her.”

There was a history of mental illness in her family; her mother was committed to an asylum after World War II because of a depressive episode, Bell says. For Styrene, the final cataclysmic event may have been a trip to New York, where X-Ray Spex played a series of shows at the legendary punk club CBGB. She was shocked by the crass commercialism of the American city, where the punk scene was awash with hard drugs. She told people that someone slipped her a narcotic and that the inadvertent experience broke something in her brain. She began seeing spaceships, aliens.

“The fact of the matter is that Poly was a person controlled by unusual forces,” says Goldman. “A sort of mental instability pushed up her innate, almost brilliant understanding of the science of life that she expressed in the music — pushed her to go from that level of insight in the early works, to become a visionary in the tradition of William Blake.”

Styrene was hospitalized. She left the band and moved in with the Hare Krishnas. She had Bell while still living at the temple. It was not an easy childhood. Mother and daughter fought. At one point, Styrene pushed her child down a staircase. Bell was raised by her grandmother. Eventually, they reconciled. And then, Styrene got sick.

“I Am a Cliché” is told from Bell’s point of view. Many other people are interviewed for the movie — Vivienne Westwood, Neneh Cherry, bandmates from X-Ray Spex, Styrene’s sister, Goldman, etc. — but Bell is the only interviewee shown on screen. The filmmakers say that was a conscious choice made partly for practical and financial reasons, but also for aesthetic ones. Sng says he was inspired by the Julien Temple film “The Filth and the Fury” on the Sex Pistols. “We wanted people, when they’re hearing the stories from the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, to be able to be transported using archive and voice.”

The resulting film is technologically and narratively a cut above the standard music documentary. The family angle makes “I Am a Cliché” more than a reclamation of a historic, overlooked artist: It raises questions about the life-work balance for artists, particularly female artists.

“The documentary gives fans an insight into the difficulties Poly faced as a sensitive artist existing in an industry that was unable to fully care for her,” says Phillips. “To see her in the context of her early upbringing, her life after X-Ray Spex and through her daughter’s eyes gives us a fully rounded vision of Poly.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.