Atlanta, a hip-hop mecca, reels as a favorite son faces sweeping criminal charges

- Share via

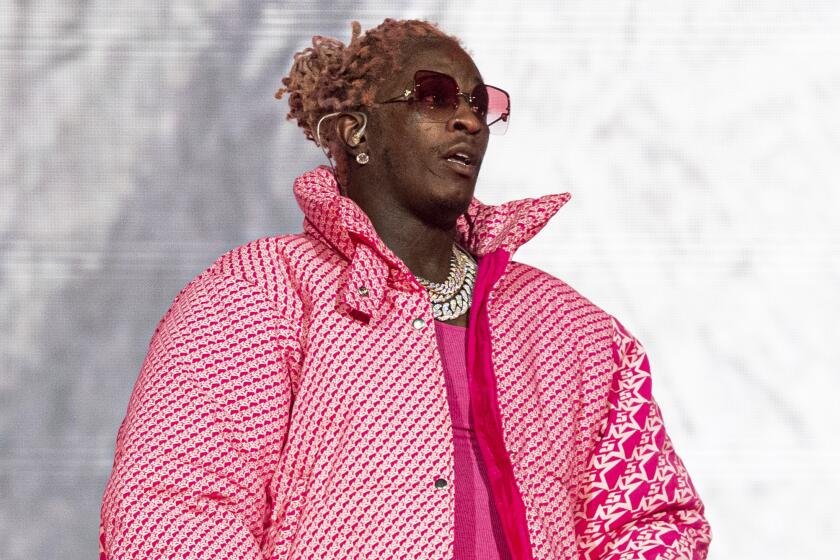

For today’s generation of hip-hop fans, Young Thug is as influential and visionary as OutKast was to previous eras of rappers. His oft-imitated style — melancholy and machine-tweaked, yet melodic and flamboyant — places him right beside Future as the defining act of contemporary Southern rap. His reach goes beyond that, though: Acts such as Lil Uzi Vert, Juice Wrld and Lil Nas X absorbed his radical aesthetics and peacocking subversions, taking them to pop radio and the Grammy stage.

That’s partly why the sweeping gang and racketeering indictment against the Atlanta rap star, born Jeffery Lamar Williams, and 27 others associated with his Young Slime Life crew (including fellow star Gunna, born Sergio Giavanni Kitchens, and Young Thug’s brother Quantavious Grier, the rapper Unfoonk) came as such a shock to his home city and to the music world.

The 56-count indictment announced Monday alleges that Young Thug is a central figure of Young Slime Life, or YSL, which Georgia prosecutors say is a gang that committed or conspired to commit a long list of crimes including murder, aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, armed robbery, carjacking, theft and drug dealing.

It’s a twist Young Thug may have anticipated in his music — “Feds came and snatched me, I don’t know, no point in asking” he rapped on 2021’s “Take It to Trial,” which prosecutors cited in the indictment — but now, it could mean a 20-year prison sentence.

Prosecutors allege that Young Thug’s violent boasts in song help prove his participation in criminal activity. His attorney calls the charges ‘baseless.’

Williams’ attorney, Brian Steel, told The Times that Williams was “not involved with any criminal street gang activity whatsoever” and described the charges as “baseless.” Prosecutors claim in the indictment that Young Thug’s YSL crew engaged in criminal activity in “protecting and enhancing the reputation, power and territory of the enterprise,” thus “demonstrating allegiance to the enterprise and a willingness to engage in violence on its behalf.”

“My number one focus is targeting gangs,” Fulton County Dist. Atty. Fani Willis said at a news conference Tuesday. “And there’s a reason for that. They are committing, conservatively, 75 to 80% of all of the violent crime that we are seeing within our community.”

There has never been another artist as established, popular and culturally important who has been accused of running such a vast criminal conspiracy, with his art used as evidence against him. It’s especially notable that it happened in Atlanta — the only city in America where hip-hop is such a foundational part of its global brand.

“Young Thug is on equal footing with OutKast in terms of what he’s meant to the culture down here,” said Rodney Carmichael, NPR Music’s Atlanta-based hip-hop critic and co-host of the podcast “Louder Than a Riot,” which examines the complex relationship between hip-hop and the justice system.

“This is a cat that, 10 years ago, people were laughing about his quirkiness as an artist even while jamming to it, and now he’s grown to be an artist who is more responsible for the sound of hip-hop right now than almost anyone else,” he said.

Young Thug, 30, is much more than a beloved regional stylist — he’s a commercial juggernaut as well. He’s topped the Billboard 200 album charts three times, most recently with 2021’s “Punk,” a typically inventive LP with cameos from megastars such as Drake, Doja Cat and Post Malone. He’s appeared on six Top 10 hits on the Hot 100, including three No. 1s. In 2019, he won a Grammy for song of the year, for his contribution to Childish Gambino’s “This Is America.”

He’s a fashion icon as well, appearing on the cover of GQ in 2016, in part for his enthusiasm for gender-bending attire like women’s dresses and elaborate pedicures (“You will never see bigger guns tucked into smaller pants,” the magazine noted.)

Young Thug has said that his music, while rooted in the street culture he grew up in, wasn’t always a documentary of his life.

“I’m big on speaking s— into existence,” he said in one interview. “I had to learn not to say s— like ‘If I go to prison...’ I had to sit back from that stuff, like gangbanging. Sometimes I forget, and it’ll be in my old music and I’m like ‘What the f—?’”

Even before his commercial triumphs, for more than a decade Young Thug had upended the sound of hip-hop from Atlanta, a place where extreme poverty, Black wealth and civic power, artistic freedom and gang subcultures intermingle in ways that make for groundbreaking music.

“Atlanta developed a relationship with the hip-hop community and its stars that you don’t see in other cities,” Carmichael said. “The last mayor [Keisha Bottoms] had Killer Mike and T.I. as part of her campaign. But the relationship between the music that’s branded the city across the world has been both contentious and collegial.”

Riffing on the lean-soaked fog and tripped-out violence of fellow Southerners Lil Wayne and Gucci Mane (who signed Thug to his 1017 label in 2013), Young Thug dropped OutKast’s fearless musicality into a new wave of dark, rippling trap music. Early singles such as “Stoner” and mixtapes like “Barter 6” and his “Slime Season” anthology announced a new inspired weirdo — “ATLien,” in local parlance — on the scene. He signed to 300 Entertainment and landed a No. 1 hit guest feature on Camila Cabello’s “Havana.”

Thug’s 2019 studio debut “So Much Fun” went to No. 1, and guest appearances on chart-topping Travis Scott and Drake singles “Franchise” and “Way 2 Sexy,” respectively, made him the go-to artist for livening up a hit rap song with otherworldly energy.

But more than most hip-hop artists, Young Thug prioritized bringing newcomers up with him through the Atlanta scene. Carmichael noted the irony that his YSL crew, which cultivated so much chart-topping talent in the South, is now being framed as a criminal conspiracy.

“Young Thug’s artistic influence on artists over the decade is impossible to count, and it goes way beyond Atlanta,” he said. “He put Gunna on, he put Lil Baby on. He famously paid Lil Baby thousands a day after he got out of jail to come to the studio and stay out of criminal activity, because Baby had a future, and now Baby is one of the biggest acts in hip-hop.”

Prosecutors, however, argue that Young Thug’s lyrics, such as those on 2018’s “Anybody” — “I never killed anybody, but I got something to do with that body ... I told them to shoot a hundred rounds ... ready for war like I’m Russia ... I get all type of cash. I’m a general” — are consonant with physical evidence and witness testimony that Young Thug participated in gang activity and violated Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) statute.

The use of Thug’s lyrics to portray him as a career criminal is a frequent tactic for prosecutors, said Dina LaPolt, a music industry attorney and member of the advocacy group Black Music Action Coalition. She cited cases such as George Forrester, whose rapping on a jailhouse phone call was introduced as evidence that helped convict him of second-degree murder and a firearm charge that led to a 50-year prison term.

“It would be like if Leo DiCaprio was charged with financial crimes and they present ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ as evidence,” LaPolt said. “Rap was born out of a reaction to urban decay, and for rap artists, it’s really important for your credibility to rap about things coming from the streets. To use that as evidence against them is very prejudicial.”

LaPolt reeled off country music songs that riffed on similar themes of violence that are obviously seen as storytelling from a distinct tradition and music culture. But in cases involving rappers such as L.A.’s late Drakeo the Ruler (who was acquitted of a murder charge and released on a plea deal) and New York’s Bobby Shmurda (convicted on conspiracy to murder, weapons and reckless endangerment charges), that same craft was thrown back at them as essentially an admission of guilt. While Young Thug’s involvement in any actual criminal activity will be decided in court, LaPolt worried that RICO laws are especially dangerous when applied to a music scene, and typical rap culture lyrical tropes could register as a confession in court.

“Most judges are older white men,” LaPolt said. “They don’t understand the culture, they’re disconnected completely. Prosecutors want to bring in lyrics that correspond with what they’re charged with because, to them, it’s a confession.”

Just days off of the indictment, Young Thug’s legacy in hip-hop is already being recast in light of the sweep of charges against him.

“YSL has a huge footprint on the culture in Atlanta, and the indictment is definitely going to have a chilling effect,” Carmichael said. “People talk about what makes Atlanta different, a Black mecca of sorts, with Black people in power. Rappers feel like they can come to Atlanta and not face the same police targeting they face in other cities. So many rappers came here to get away from that in their own towns. That may be the thing that takes the biggest hit.”

On Wednesday morning, Gunna — just days off his Met Gala appearance, with a No. 1 album and a “Saturday Night Live” gig behind him this year — was booked into Fulton County Jail to face a charge of conspiracy to violate the RICO Act. After police raided Young Thug’s Buckhead home, prosecutors added seven more felonies to his list of charges.

“Now they’re going to feel a target on their backs,” Carmichael continued. “There’s no question that will have an effect on the culture.”

Times staff writer Jenny Jarvie contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.