- Share via

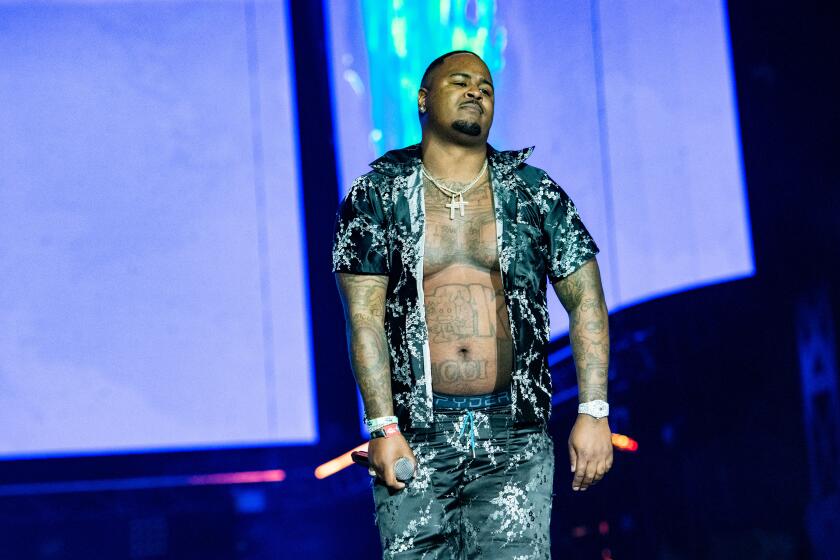

In December, the South L.A. rapper Drakeo the Ruler arrived in a Rolls-Royce to perform at the Once Upon a Time in L.A. festival at the Banc of California Stadium. For the 28-year-old Drakeo, born Darrell Caldwell, the show was a triumphant return to the stage after three years’ incarceration. The festival, headlined by rappers Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube and YG, was overseen by mega-promoter Live Nation and local organizers C3 Presents, Jeff Shuman and Bobby Dee Presents.

What happened that night would become just the latest in a series of high-profile acts of violence that have shadowed the concert business, and the world’s largest promotion company, for years.

Drakeo and his brother Devante Caldwell, a 27-year-old rapper who performs as Ralfy the Plug, passed through two security checkpoints to enter the backstage artist area off Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. The first was a booth of unarmed staffers checking passes.

At the second, a few guards from a security subcontractor scanned Drakeo’s Stinc Team crew with a metal detector and a drug-sniffing dog. The guards confiscated pepper spray from Drakeo’s bodyguard, but Caldwell recalled cars of VIPs driving through unsearched.

Members of Drakeo’s crew were familiar with the area’s gang violence and felt uneasy. They didn’t see any security cameras or law enforcement backstage.

“It was supposed to be a safe place, but once we got past everybody, there ain’t no security back there,” Caldwell said. “It seemed like they stopped caring and just let anybody in.”

Minutes after they arrived, dozens of men attacked Drakeo and his crew. One assailant pulled an “edged weapon,” according to a California Highway Patrol report, and stabbed Drakeo in the neck, leaving him bleeding in Caldwell’s arms.

Drakeo was pronounced dead at California Hospital Medical Center in downtown L.A. around 3 a.m. the next day.

“Nobody came to help,” Caldwell said. In a February negligence lawsuit filed against Live Nation, he claimed that nearly 30 minutes passed before medical personnel arrived.

“They didn’t lock the perimeter down like in the movies. The security presence was zero until the ambulance got there,” he continued. “Once I’d seen it happen, it was like, ‘This is real blood, and there ain’t nobody here that can stop that blood from coming out.’”

Concerts can, of course, be fertile terrain for risky behavior such as drug and alcohol abuse that can result in serious accidents or deaths. And some tragedies — such as the mass shooting at the 2017 Route 91 Harvest festival in Las Vegas that killed 60 people, or the 2017 suicide bombing that killed 22 people at the Ariana Grande concert in Manchester, England — may be beyond the control of promoters.

Security arrangements vary depending on the concert, but at Once Upon a Time in L.A., Astroworld and other events, Live Nation has been repeatedly accused of failing to follow industry safety protocols for controlling large crowds and protecting concertgoers and performers from weapons and faulty stage construction, according to a Times review of wrongful death and injury lawsuits as well as interviews with security experts, Live Nation employees and witnesses to concert tragedies. The alleged breaches include disregarding crowd safety plans and hiring too few or poorly trained security and other personnel, creating potentially hazardous conditions for millions of fans who flock to concerts annually.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Live Nation and the vendors it works with have been sued dozens of times over hundreds of deaths and serious injuries at concerts and festivals in the last 15 years, including the crowd rush at Astroworld in Houston in November in which 10 people died. In May, comedian Dave Chappelle was attacked by a knife-wielding fan onstage at the Hollywood Bowl during a Live Nation-promoted show involving the same Northridge-based security firm, Contemporary Services Corp., that worked on Astroworld with other firms.

Since the start of the modern live music industry, there have been concert disasters in America.

In 1969, members of the biker gang Hells Angels were hired to work as security for the Rolling Stones’ set at the Altamont Speedway Free Festival in Northern California. One fan was stabbed to death; two died in a hit-and-run and another drowned. In 1979, 11 people were trampled to death at a Cincinnati show where the Who performed. Fires, rapes and chaos marred Woodstock ’99. A hundred fans perished in a fire at the Station nightclub in Rhode Island in 2003, and 36 died in a blaze at the Ghost Ship warehouse in Oakland during a concert in 2016.

But November’s Astroworld disaster — an event likened to “hell on Earth” for many of the 50,000 fans — was a wake-up call for the industry and Congress. In a letter to Live Nation Chief Executive Michael Rapino, the House Committee on Oversight and Reform said it was troubled by the catastrophic incidents at Live Nation shows.

“The tragedy at Astroworld Festival follows a long line of other tragic events and safety violations involving Live Nation,” the letter said.

“One reason for this investigation is because Live Nation concerts are still taking place around the country,” Rep. Al Green (D-Texas), who signed the letter to Rapino, told The Times. “If there are other instances where a person has been harmed, we need to know the extent.”

As the civil lawsuits against Travis Scott and Live Nation pile up, legal experts say that Scott could also face arrest for his part in the Astroworld tragedy.

Attorney Jovan Blacknell, who is representing Devante Caldwell and Drakeo’s family in suits against Live Nation, said: “It certainly is a pattern by Live Nation, and I don’t think they’ve ever truly been held accountable for any of it.”

Live Nation has said it had “no liability” in the rapper’s death and could not have foreseen the criminal activity that occurred.

“We’re heartbroken whenever someone is harmed or life is lost at a show,” said Kaitlyn Henrich, a spokesperson for Live Nation. But she disputed claims that the concert giant has cut corners on safety and security at any of its events.

“Live Nation successfully promotes and operates more live events at scale than any other company in the world, on average there are 268,000 people attending 110 Live Nation shows every single day,” Henrich said, noting that more than 1 billion fans have attended Live Nation events since the company was founded in 2005.

At Once Upon a Time in L.A., she added, attendees were subject to “a full body pat-down, magnetometer screening, bag screening and a COVID-19 check. California Highway Patrol, LAPD, private security, the fire department and fire marshal were also on site. “ Everyone entering the backstage area, including artists and those arriving in a vehicle, had to go through security checks, she said.

“Every event is unique — from location, to weather, to vendor support, and many more factors. There are many variables that can connect back to safety and security,” Henrich said. “It’s misleading to say there is a pattern of issues when the nature of the incidents at those events was fundamentally different.”

A concert juggernaut

Live Nation’s origins date to 1997, when entertainment mogul Robert F.X. Sillerman founded concert promoter SFX Entertainment, aiming to buy up local promoters and combine them into a national firm. Such promoters broker live performances for artists, handling everything from booking venues to hiring staff for events and marketing concerts to fans.

Clear Channel Communications bought the company in 2000 and spun it off as a new firm, Live Nation, in 2005. Five years later, Live Nation merged with Ticketmaster, creating a multibillion-dollar behemoth that books concerts, manages venues and operates ticketing all at once. The merger was approved despite some concerns raised by members of Congress.

The COVID-19 pandemic gutted Live Nation’s revenue, which plummeted 84% in 2020 to $1.86 billion. But as the concert business has revived, Live Nation’s business has roared back, with the company reporting $4.4 billion in revenue in the second quarter of this year. Its Ticketmaster unit sold 100 million tickets, beating 2019’s pre-pandemic highs.

Investors, including Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund — which bought a 5.7% stake in the company valued at $500 million in 2020 — have cheered the results. Shares in Live Nation Entertainment have increased about 20% in the last year to close at $96.47 on Thursday.

“We think we’re in for multiple record years of growth,” Rapino said in a recent earnings call.

But Live Nation acknowledges that Astroworld and other disasters could imperil that growth.

In its 2021 annual report to the Securities and Exchange Commission, the company said that “hundreds of civil lawsuits have been filed against Live Nation Entertainment, Inc. asserting insufficient crowd control and other theories. These events are the subject of an ongoing investigation by local authorities in Harris County, Texas, and are the subject of an inquiry we received from the House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform.”

“These effects could have a material impact on our business.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

‘It was so chaotic’

Every music festival begins with an event operations plan, a master document outlining safety procedures for nearly every conceivable incident that must be approved by local governments. The so-called EOP details the festival’s physical layout, its management structure, an incident command system and other vital information. It lists managers responsible for subcontractors, how the security and medical staff are deployed, what equipment (such as barricades) will be used, and who responds to possible threats such as riots, terrorism, traumatic injuries and inclement weather.

A global conglomerate like Live Nation can take varied roles in producing events, from the full range of promotion duties at the venues it owns to simply hosting sales on Ticketmaster for third parties. But most often, under such plans, ultimate responsibility for safety and security lies with the concert promoter, which appoints a safety and risk director to oversee all aspects of securing the show. The director, either a full-time staffer or a contracted expert, works with the promoter, the venue and the third-party security and event services companies. It is often these third parties that provide part-time or full-time on-site staffing.

As it has rebounded, Live Nation has faced growing scrutiny over the adequacy of its event operation plans and how they are enforced.

At Lovers & Friends, a Live Nation festival held at the Las Vegas Festival Grounds in May, three people were taken to a hospital after false reports of gunfire led to a massive rush away from the stages. Live Nation oversaw security at the event.

In June, videos showed fans screaming in a stampede from a Phoebe Bridgers concert at RBC Echo Beach, a Toronto outdoor venue booked by Live Nation, which also handled security. Two attendees were hospitalized for injuries.

Music festival goers recount the chaos of that day, when eight people died, two dozen were hospitalized and scores more were injured.

One full-time Live Nation security guard, who asked not to be named because he still works for several of the company’s venues around Southern California, believes “understaffing” is a persistent problem at some Live Nation events.

He cited an experience patrolling the backstage area at April’s Smoker’s Club festival at the Glen Helen Amphitheater in San Bernardino County. The festival, headlined by rappers Kid Cudi, A$AP Rocky and Playboi Carti, turned violent when the audience ran over security barriers and the crowd rushed the stage during Carti’s show.

“It was so chaotic, all the people on the lawn stormed over the railing and rushed the stage. We shut down for an hour and a half, there were a lot of fights,” the guard said. He added that Live Nation did not hire enough security to keep the crowd under control. “It’s up to the promoter how much security they want, which can be a major problem,” he said.

Live Nation’s Henrich said that “security was led by festival security experts who specialize in multistage events and have decades of experience running security for some of the largest festivals in the country. Venue security staff were on site as well, however many of them were not privy to all aspects of security operations. The festival security team saw chatter on social platforms of fans trying to make plans to storm the gate, and stepped up security in accordance with protocols, which successfully prevented a breach from occurring.”

At Chappelle’s performance, part of the Netflix Is a Joke festival, 23-year-old Isaiah Lee eluded stage security and tackled Chappelle midset, while carrying a replica handgun with a folding knife blade inside, authorities said. Lee had no credentials that should have allowed him onstage, they said. Sources with the Los Angeles Police Department told The Times that metal detectors and bag searches failed to discover his weapon.

A person close to Live Nation said that, although the firm marketed and sold tickets to Chappelle’s show, the Hollywood Bowl handled security for that May event.

Sophie Jefferies, a spokesperson for the Los Angeles Philharmonic Assn., which operates events at the Bowl, confirmed that it is responsible for security at the venue. The association has said that it is reviewing safety procedures “so we can continue to provide a safe and secure environment at the Hollywood Bowl” and that it has implemented additional security measures, including increasing security staff on site to assist with bag checks.

Other concert promoters have faced questions about event security. In 2016, a fan shot and killed singer Christina Grimmie at an Orlando, Fla., concert promoted by AEG.

But Live Nation has confronted persistent complaints about its safety practices for years.

In 2013, Live Nation’s Canadian division faced eight charges under the Occupational Health and Safety Act after a stage collapsed at a Toronto Radiohead concert in 2012, killing the band’s drum tech Scott Johnson. Ontario’s Ministry of Labor alleged that Live Nation Canada, along with a staging company and an engineer, “failed to ensure the structure was designed and constructed to support or resist all likely loads and forces.”

The charges were eventually dropped because the statute of limitations had expired after five years.

The following year, Live Nation was among 18 defendants that paid a $39-million settlement after a 2011 stage collapse at the Indiana State Fair killed seven and injured dozens during a concert by the country duo Sugarland. Seventy-mph winds knocked stage equipment into packed crowds.

Henrich said Live Nation did not oversee stage construction for either event.

The company has also faced wrongful-death suits that foreshadowed tragedies like Drakeo’s killing.

In 2014, Eric Nathan Johnson II, 38, of Oakland was killed backstage at the Under the Influence of Music festival at the Shoreline Amphitheatre in Mountain View, Calif. Johnson, a concert promoter, had booked performer Young Jeezy to appear at a nightclub after the show. After an argument in a backstage parking area, a man shot Johnson in his car.

Jeezy and five others were arrested on suspicion of weapons possession in Irvine later that month in connection to the shooting, though their criminal case was dismissed.

In a civil suit, Johnson’s family alleged “Live Nation … failed to employ reasonable security measures to prevent guns from being brought into the Shoreline Amphitheatre.” The suit said the tour’s security rider barred uniformed police officers from being present in the backstage area and that Live Nation “condoned and/or permitted these dangerous conditions to exist.”

Live Nation argued that it could not foresee such an incident. “There simply is no evidence of prior incidents similar to the backstage shooting that occurred at the Shoreline Amphitheatre,” the company said in a filing.

A Santa Clara County judge ruled in favor of Live Nation, and the order is under appeal.

Two years later, in 2016, Ronald McPhatter was working as personal security for the artist Troy Ave at a Live Nation-produced concert at New York’s Irving Plaza. Daryl Campbell, a hip-hop podcaster embroiled in a feud with Troy Ave, attacked him backstage. McPhatter intervened, and Campbell shot and killed McPhatter, according to prosecutors. Campbell was charged with murder and later pleaded guilty to two federal gun charges.

A wrongful-death suit filed against Live Nation alleged that the company failed to “staff the venue with competent personnel” and demonstrated a “willful disregard for the health and safety of invitees of the premises.”

In response to the suit, Live Nation said, “The injuries and damages alleged were caused by the contributory negligence and/or culpable conduct of Ronald McPhatter” and that “plaintiff failed to use available means to mitigate damages.”

The case was settled last year. Terms were not disclosed.

‘Trapped and crushed’

Astroworld was Live Nation’s deadliest disaster since the 2017 Las Vegas festival mass shooting.

Many experts and government officials believe the tragedy was preventable and have cited key security shortcomings, including a failed chain of command to stop the show, poorly designed barricades and a flawed festival layout. No criminal charges have been filed.

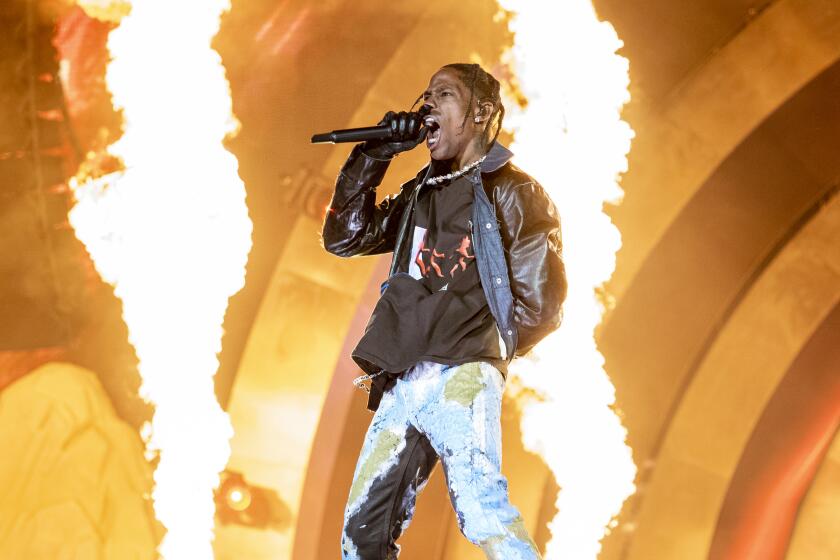

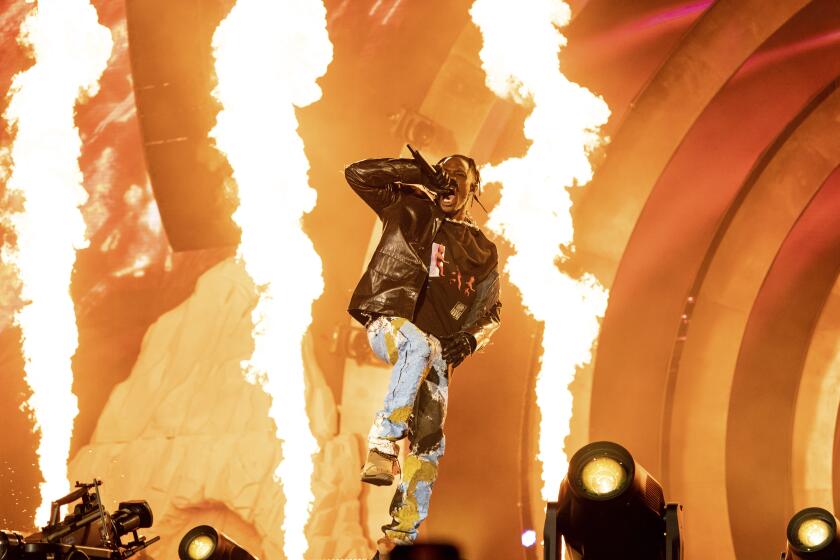

Even before Travis Scott took the stage on Nov. 5, he had been involved in at least two other crowd-control incidents. Scott pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge of disorderly conduct. He also pleaded guilty in 2015 to a misdemeanor charge of reckless conduct for similar behavior at Lollapalooza.

For the record:

12:19 p.m. Aug. 22, 2022An earlier version of this story said fans at Astroworld climbed onstage to get Travis Scott’s attention. They climbed on a platform overlooking the stage.

Signs of potential trouble at Astroworld were apparent early. Fans breached perimeter barricades before gates opened at 10 a.m. By early afternoon, thousands of gate-crashers had used bolt cutters, rushed entrances and overturned fences to gain access. Fans swarmed an interior merchandise area and the VIP section, toppling crowd-control barriers. Just after 4 p.m., Houston Police Chief Troy Finner met with Scott in his trailer, reportedly to warn him of safety concerns.

Immediately after Scott took the stage at 9:01 p.m., an overpacked crowd heaved against the railings. Terrified concertgoers screamed to stop the show; some climbed on a platform overlooking the stage to get the rapper’s attention. “What the f— is that?” Scott said as an ambulance struggled to cut through the crowd to reach injured fans. “If everybody good, put a middle finger up to the sky! You know what you came here to do.”

Though officials declared it a mass casualty event about 40 minutes after Scott’s set began, the show continued until 10:14 p.m. In a copy of Astroworld’s event operations plan viewed by The Times, the positions of executive producer and festival director, each explicitly given “authority to stop show,” were left blank.

Ten people, including a 9-year-old, died of compression asphyxia, medical examiners said, while thousands of people were injured.

More than 300 lawsuits have been filed against Live Nation and other parties over the injuries and deaths. One suit represents 282 victims and is seeking $2 billion in damages against Live Nation, local promoter Scoremore and others.

“Many in the crowd were knocked to the ground and trampled, some were trapped and crushed against other concert attendees, while others were compressed against metal barricades,” the suit states. “The resulting catastrophic incident and carnage were easily foreseeable and preventable.”

Live Nation’s Henrich said “safety and security protocols for Astroworld reflected months of coordinated planning and iteration with industry-leading experts, local public safety authorities and many other stakeholders. The detailed investigation is still ongoing, so anyone making conclusions at this point is doing so without all the facts.”

Security experts said the deaths and injuries were preventable.

An executive who has worked on medical and safety plans for major Live Nation festivals and who asked to not be identified because they still work with the company said, “Putting a huge, well-known artist on a small stage with 50,000 people in attendance, and low-draw artists on a competing stage, will almost certainly lead to a crowd surge.”

Astroworld “highlights the importance of having a well-staffed, unified command who can identify crowd surges and make calls for a full show stop,” the first-response executive added.

Rich Thomas, a former vice president for one of Live Nation’s festival promoters, Insomniac, said the company should have been better prepared for volatile crowds at Astroworld.

“Given the challenges live music has faced in the last two years, promoters ... might get greedy and oversell, or maximize profits and minimize things like crash barricades,” said Thomas, referencing a type of supported wall that keeps fans out of the aisles. (Thomas’ former employer, Insomniac, has also employed Seyth Boardman, who prepared Astroworld’s security plan with his firm B3 Risk Solutions.)

Thomas, who worked on events like the hip-hop-heavy Hard Summer and electronic dance music event Electric Daisy Carnival, said cost-cutting promoters might think they “don’t need 100 security guards, they just need 50. Or that they don’t need stage barriers with foot plates that can’t be tipped over.”

Astroworld’s event operations plan called for supported barricades only at the stage front, and “bike rack-type crowd control barricades,” concrete bollards (vertical posts) and less-rigid fencing at the perimeter and interior.

In response to the incident, the Texas Task Force on Concert Safety — composed of industry experts, first responders, law enforcement and government officials — prepared a report for Texas Gov. Greg Abbott. Although the report’s recommendations did not assign specific blame, lax security, faulty crowd control and a vague chain of command were raised as concerns.

The Texas report said that “agreed-upon show-stop triggers” were essential and that security “must have adequate training.” Event permitting requirements are currently “inconsistent … which can lead to forum shopping by event promoters.”

The panel said barricaded areas should have had “rounded areas with forward and backward egress, rather than angular areas where people can get trapped. … There is a serious safety risk if venue borders are susceptible to a breach.”

Ty Richmond is an executive at the security consulting firm Allied Universal, which contributed to the task force’s report on Astroworld. He agreed that insufficient training and a lack of agency coordination can contribute to breakdowns.

“You have to ensure everyone has expertise in those areas,” said Richmond, the former vice president of global security for Sony Pictures Entertainment. “It’s fundamentally about ‘Is your security service provider capable of hiring an accurate deployment of personnel who are vetted, screened and trained?’ As fundamental as that sounds, it’s even more critical now.”

Randy Phillips, the former president and chief executive of AEG Live — a rival to Live Nation — attributed the repeated tragedies partly to “trying to cut costs to spend as little as possible.”

Phillips, whose former company produces festivals including Coachella, said Live Nation and Scoremore should have anticipated Astroworld’s security and stage-design issues.

“The problem there was that most fests create specific pens with limited capacity. I’m not sure there were enough barricades there,” Phillips added. “I’m sure the investigation is being done, but that’s a huge problem.”

Live Nation has denied claims that it failed to invest in security at Astroworld and other events. A source close to the company said it hired 1,700 security staffers for Astroworld — 1,000 more than initially budgeted.

“Since 2017, Live Nation’s in-house global security team has more than quadrupled,” Henrich said. “Live Nation has also spent tens of millions of dollars enhancing security operations and training, as well as leveling up technology and equipment at its venues and festivals.”

Outsourcing security

Although promoters may have some full-time security staff, most, including Live Nation, contract much of their security and guest services through firms like Contemporary Services Corp., one of the largest such firms in the country.

To staff shows, Live Nation will hire a firm like CSC to arrange enough security to meet the needs of the event plan. Those firms will hire and train subcontracted staff, who are mostly part-time employees paid hourly per event.

Founded in 1967, CSC provides event services at gatherings as big as the Super Bowl, the Olympics and presidential inaugurations. It also supports pro sports games and concert tours by bands such as U2 and the Rolling Stones.

But CSC has faced dozens of lawsuits alleging a lack of staff training, wrongful deaths and violent assaults by staff at sports and music events. And in 2020, CSC settled a California class-action suit from employees claiming lost wages and insufficient safety equipment.

One pending suit alleges that at a 2018 James Taylor concert at the Hollywood Bowl, a woman was “tackled to the ground and handcuffed” by CSC guards. Last year the University of Houston ended its security contract with CSC after its guards assaulted fans after a football game. University of Houston athletics Vice President Hunter Yurachek said in a statement that “I am extremely disappointed and angered with the actions taken by individuals employed by our security contractor CSC.”

CSC job listings for event staff show that typical pay is under $20 an hour, and its own advertising for job openings has told candidates, “Why pay upwards of $100 for a ticket when you can experience the event with the CSC family and be compensated for it?”

“I feel a lot of those contractors think, ‘I’m not paid enough to give a damn,’” Insomniac’s Thomas said about subcontracted security staff. “They’re asked to do an incredibly critical job, but they’re underprepared to deal with what we saw at Astroworld.”

Regarding its relationship with CSC, Henrich said: “Live Nation partners with many specialized security experts on its events. Hiring specialized security personnel for large-scale festivals and events is common practice in the industry, which ensures that these crucial functions are staffed competitively by experienced and knowledgeable professionals with the requisite background and experience for a particular show.”

CSC executives did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The company has denied all the allegations made in the Astroworld suits, saying that “any injury or damage suffered” by plaintiffs was “caused by the conduct, acts or omissions of third parties” over whom it had no control, citing the negligent behavior of concertgoers.

‘They’re not looking after us’

Drakeo’s killing devastated his family and team.

At the time of his death, he’d recently collaborated with superstar Drake on the single “Talk to Me,” and was poised to become L.A.’s next national hip-hop star. He is survived by Caldwell and other siblings, his mother and his young son, each of whom has pending lawsuits against Live Nation.

Eight months later, the case remains unsolved with no arrests, a source of frustration for those closest to him.

Eyewitnesses contend that security was lacking at the Once Upon a Time in LA festival, at which rapper Drakeo the Ruler was fatally stabbed backstage.

“You got Astroworld, then Drakeo, and Live Nation’s behind it all,” said Drakeo’s producer JoogSZN, who was with him the night of the slaying. “How is it they’re not looking after us? If that was Taylor Swift onstage, it wouldn’t have gone down that way. There should have been more metal detectors or patrols. I feel that absolutely, at this point, they just don’t care.”

Live Nation’s Henrich said that the company “employs dedicated experts, implements extensive safety policies and programs, and takes many other steps to ensure that our events are safe and secure for attendees, staff and artists. The very nature of security requires protocols to be adjusted and enhanced over time and this is something Live Nation takes very seriously. For example, following the Astroworld festival, Live Nation has tapped festival operations and security experts from around the world who are actively working with the hope of creating and advancing additional safety and security measures.”

In response to Caldwell’s suit, Live Nation said in a July court filing, “Case law does not support the logic between imputing liability for prior similar incidents based on alleged conduct that occurred in the city surrounding the subject premises. Mere allegations of gang activity … in South Central Los Angeles should not be considered in determining foreseeability of the subject incident.”

Live Nation has major festivals such as Primavera Sound, Ohana Festival and Besame Mucho booked in the L.A. area this year. Even Scott is eyeing a return. He was booked to perform at AEG’s Day N Vegas in September before the promoter canceled the festival.

Today, Caldwell spends much of his time at a “safe house” — an apartment rented by the label for the surviving members of Stinc Team, who are deeply traumatized by Drakeo’s slaying. They all fear further violence.

“Drakeo was the truth, man. I was off the Earth for weeks after,” Caldwell said, his eyes red and face streaked with tears. “It just didn’t make any sense. If you can’t keep the people you hire to play for you safe, then you can’t keep the fans safe either.”

Times staff researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.