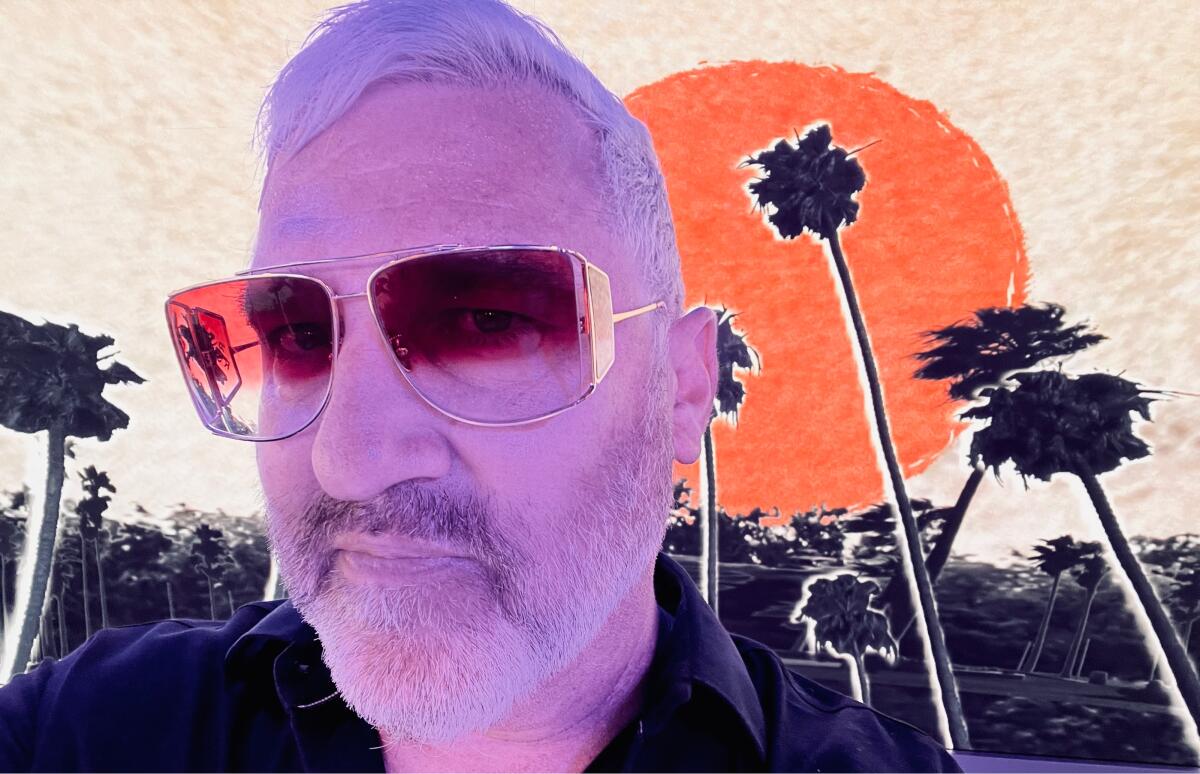

Greg Dulli walks into a bar...

- Share via

Greg Dulli can vividly compare the economics of being a bar owner to the economics of being a rock musician.

“If you’re in the Rolling Stones, this is a pittance,” he says, gesturing toward his surroundings as he sits in a black-leather booth at Atwater Village’s Club Tee Gee — one of three spots he co-owns in Los Angeles — on a recent afternoon. “If you’re in the Afghan Whigs,” he adds with a grin, “you’re psyched.”

Dulli, 57, is in the Afghan Whigs — has been, in fact, since 1986, when he formed the shadowy grunge-soul band in Cincinnati, not far from his hometown of Hamilton, Ohio. Built around Dulli’s tortured-beefcake wail, the group found alternative-rock success in the post-Nirvana ’90s with albums like “Gentlemen,” on which the frontman dissected a toxic relationship in brutally unsparing detail; MTV’s embrace of the LP’s breakout single, “Debonair,” even led to Dulli’s being cast as the voice of John Lennon (alongside Dave Pirner’s Paul McCartney and Dave Grohl’s Ringo Starr) in the 1994 early-Beatles biopic “Backbeat.”

Decades later, after a breakup and a reunion and a number of personnel changes, the Whigs are still going. On Friday the band will release its ninth studio album, “How Do You Burn?,” and play the first date of a U.S. tour that will keep Dulli and his mates on the road through mid-October.

“We just did three weeks in Europe, and the show in Prague — I mean, it was why I still do it,” says the singer, who beyond the Afghan Whigs has made solo records and played with the Twilight Singers and as half of the Gutter Twins with Mark Lanegan. “Absolute emotional ecstasy.”

In a year in which Spanish-language artists have increasingly dominated the charts, Rosalía’s ‘Motomami’ may be a blueprint for all of pop moving forward.

As much as music means to Dulli, he spends a significant amount of his time these days tending to his businesses: Club Tee Gee, the dive-y Footsie’s in Cypress Park and the Short Stop near Dodger Stadium, along with two more bars he co-owns in New Orleans, where Dulli lives when he’s not in L.A. The Short Stop was his first investment; he paid $15,000 for his initial stake in 2000 as the Whigs’ original incarnation was beginning to fall apart.

Yet Tee Gee, which he’s had for about four years, is his favorite, he says. (For one thing, it’s closest to his house.) Dressed in a golf shirt and basketball shorts, his once-inky hair gone snowy white, Dulli eagerly points out some of the décor elements he changed when he bought the bar from the family of one of the men who’d opened it in 1946. His business partners in Tee Gee are “an ex-marketing exec with a finance major, a lawyer and a CPA,” he says. With a laugh, he adds: “All the s— I’m not.”

Dulli, who carries himself like a minor character in a Martin Scorsese movie, knew bars well before he started playing them with the Afghan Whigs. Growing up, he had two uncles who owned joints in Hamilton where he’d hang out and play shuffleboard. “It was a familiar setting,” he says now. “And I understood that both my uncles did all right with it.”

Indeed, despite his various indulgences as a young rock star — and with the crucial guidance of a business manager “who was like, ‘Capital gains — follow my lead’” — Dulli was smart with the money he began making as the Whigs took off. “It was real estate immediately,” he says. “Bought my first house when I was 27, then another one by the time I was 29.”

Asked whether L.A. or New Orleans is the bigger drinking town, Dulli says New Orleans is “a more constant drinking town,” not least because bars can operate around the clock there. “But I’ve learned that nothing good is ever happening at 5 a.m., unless it’s Mardi Gras,” he says. “I’m not staying open for five sketchy motherf— who are just tweaking and trying to keep their heart rate down.”

Dulli’s new music still exudes a bleak wee-hours atmosphere: “The Getaway” is narrated by someone “waiting for the night as I destroy the day,” while the singer in “A Line of Shots” ponders “a simple lie to call upon your sympathy.” Throughout “How Do You Burn?” — on which Dulli’s collaborators include founding Whigs bassist John Curley as well as members of the Raconteurs and Blind Melon — the band combines the kind of spiky guitars and throbbing R&B grooves Dulli’s loved since he was a kid obsessed with Led Zeppelin and Motown, Aerosmith and the Ohio Players.

Having called it quits after touring behind 1998’s “1965” album — Dulli was “kind of done with music” and briefly tended bar at the Short Stop before turning to the Twilight Singers and the Gutter Twins — the Afghan Whigs got back together in 2012, at first with founding guitarist Rick McCollum on board. But McCollum didn’t last long: “I think he’d just gotten settled in whatever his life was,” Dulli says. “He was like an alien to me.” The band made two albums, 2014’s “Do to the Beast” and 2017’s “In Spades,” with guitarist Dave Rosser, who died of colon cancer shortly after the release of the latter.

Dulli conducted remote recording sessions for “How Do You Burn?” as his bandmates were scattered across the country during the COVID pandemic. “That first song is four people in three states,” he says of the LP’s pummeling opener, “I’ll Make You See God.” But it doesn’t sound pieced-together at all; Dulli, an admitted control freak, reckons the other players actually felt more invested in the music because they were creating their parts out from under his watchful eye.

“You can’t be Paul McCartney all the time,” he says with a shrug.

His singing — snarling, chesty, slightly haunted — is particularly strong, which he credits in part to his work with Lanegan, the gravelly voiced ex-Screaming Trees frontman who had perfect pitch, according to Dulli. “It was ravaged but always in key,” he says of Lanegan’s signature croak. Of his own vocals, Dulli says, “In all modesty, I think I sound way better now than I used to.” The worst singing he ever did, in his view, is on the album widely regarded as his best.

“I did almost all the vocals for ‘Gentlemen’ in like three days, and I was rocking and rolling back then,” he says. “Staying up all night long, doing things that are not beneficial to your throat.” One takes his point, though might it also be the case that — on an album about desperate people in a desperate situation — it’s precisely that ragged quality that makes the performance?

“If you like Method singing,” he says, “I suppose it’s a master class.”

From intimate clubs to picturesque outdoor theaters to state-of-the-art arenas and stadiums, there’s no better place to see live music than SoCal.

Dulli, who’s never married and has no children, is frank about his history of substance abuse. “When I was young, I read Creem magazine, especially whenever they’d talk to Keith Richards,” he says. “I loved Keith Richards. And I was like, I can’t wait to do drugs. Drugs look f—ing fun. I’m gonna do all of them. And I did.” By the late ’90s he’d entered a “self-destructive phase,” as he puts it; he’d become “mean and volatile,” to the point that “even my staunchest supporters were telling me, ‘You suck.’ So I pulled myself out of that phase, and I’ve never returned to it.”

Has his ability to do that surprised him?

“I have an iron will,” he says. “When I make up my mind, it’s done.” These days he drinks tequila, mezcal and gin; he used to like bourbon, though he’s lost his taste for “the brown downers.”

Dulli says that losing Lanegan and Rosser — as well as his friend Shawn Smith, who played with the Twilight Singers, and his former booking agent, Steve Strange — has made him think about his own mortality. “I’m moving into the autumn of my days,” he says. Of Lanegan’s death in February, the cause of which hasn’t been publicly revealed, Dulli says he knows nothing beyond the fact that Lanegan’s health was seriously damaged by a bout with COVID last year.

Before that, Dulli says, Lanegan had been “swimming in some conspiracy theories” regarding the pandemic — “classic foil-hat stuff about vaccines and Bill Gates. I was like, ‘Dude, come on.’ But I think he moved past that.” Dulli talked with Lanegan on the phone a week before he died, he says, “and he seemed fine to me then.”

The spread of COVID misinformation is just one aspect of a political climate that Dulli jokingly says makes him wonder “when Ashton Kutcher’s gonna pop out and tell us we’ve all been punked.” This summer the singer went home to Ohio to visit his mom. “I’m driving into my old town and I see all these flags with the name of a person who isn’t president anymore,” he says. “Why are you flying that flag? That’s a cult flag. Is this Jonestown?”

He shakes his head as he continues: “You know, when I was young, you could get into it with somebody who didn’t agree with you, then have ice cream afterwards. Now motherf— wanna kill you.”

Asked whether he’s supporting Karen Bass or Rick Caruso in L.A.’s mayoral race, Dulli says, “Straight up, I’m a socialist, so I’ll just lay that there and you can probably answer your own question.”

Is there any tension between being a socialist and a small-business owner?

“A little,” he says with a laugh. “My partners rein in my socialism sometimes. They’re like, ‘Now, Greg…’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.