- Share via

’Tis the season for Dean Martin — the one month of the year when he’s ubiquitous once again, haunting tinseled malls and cocktail-party playlists, a ghost of Christmas past whose voice can make even the balmiest West Coast day feel like a marshmallow world in the winter. Of the 10 most-played Dino tracks on Spotify right now, seven are holiday novelties — jovial corn for popping. “Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!” is No. 1, with 351 million streams, presumably racked up largely between Black Friday and New Year’s Day.

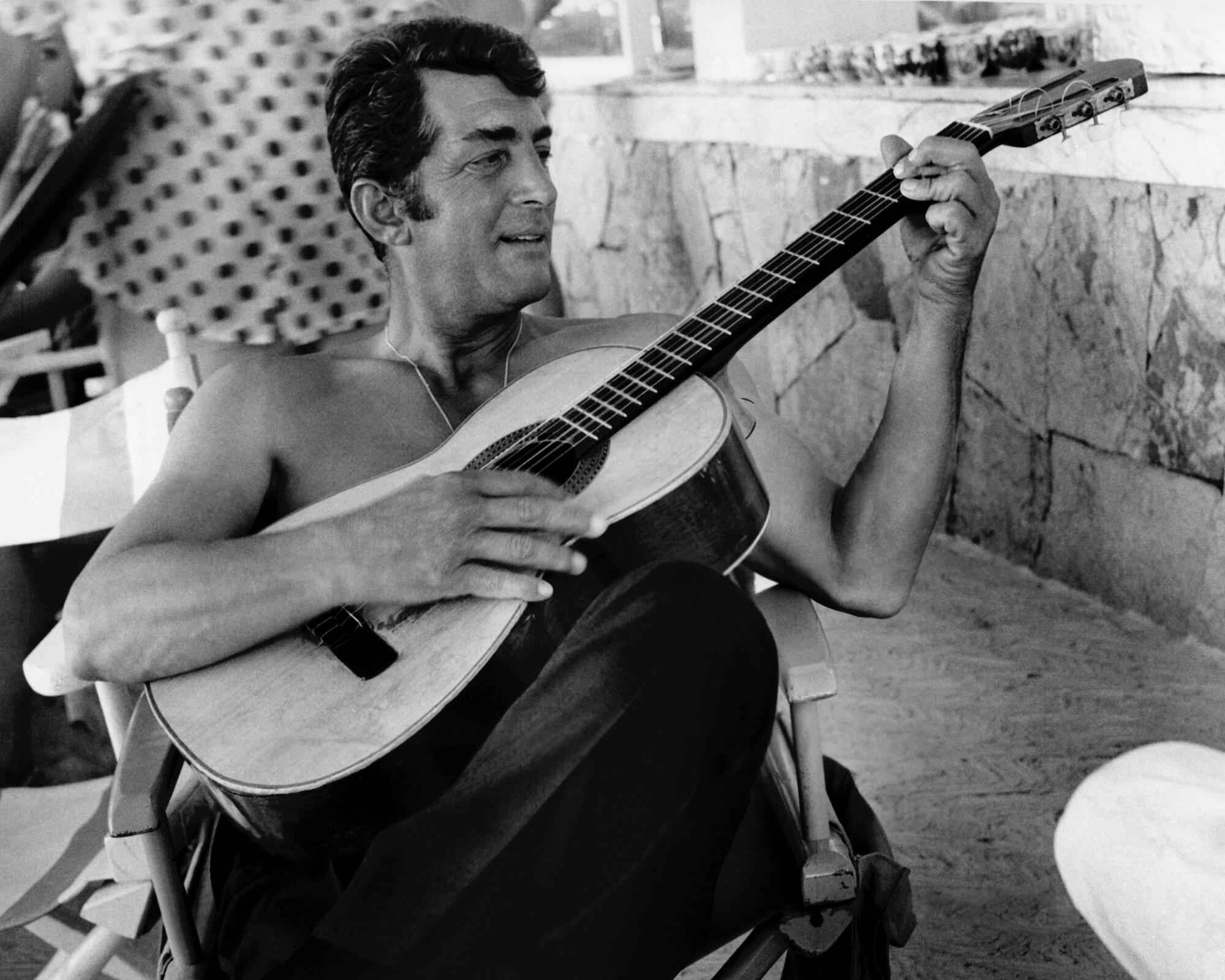

It’s a strange state of affairs for an artist who was once a year-round fixture of the entertainment landscape — a genial omnipresence whose breezy, boozy, hardly-workin’ charm came across on every platform he touched, from stage to screen to radio to records, in comedy and drama and celebrity roasts.

Lately, a guy named Jimmy Edwards has been thinking a lot about Martin’s place in the modern media landscape — where Dean is right now, some 27 years after his death at age 78, and where he ought to be, culturally speaking. Edwards is a music industry veteran whose résumé includes a decade at Warner Music Group as well as a few years at Frank Sinatra Enterprises. Last summer he became the president of Iconic Artists Group, a company that manages the legacies of a roster of eminent rock and pop artists, including the Beach Boys, David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Linda Ronstadt and Nat “King” Cole.

Founded in 2018 by megamanager Irving Azoff — legendary in his own right for his pugnacious advocacy of the interests of artists like the Eagles — Iconic is part of a growing sector of firms making big bets on the enduring appeal of 20th century superstars and the long-term exploitability of the work they have (or will have) left behind.

“Irving deeply cares about his artists,” Edwards says, “and he wants to make sure their legacies are preserved.” Iconic, Edwards says, assumes the position of the artist at the negotiating table, managing present-day branding opportunities while looking ahead to the ways in which audiences might encounter these artists in emerging and future mediums.

Last month, Iconic acquired an equity position in the rights held by the Dean Martin estate, which includes his music, vast amounts of work across the audiovisual spectrum, along with a lifetime of archival ephemera — and will use all that material to put Dean back in front of the whole world again. A new documentary film is now in discussion; a full-fledged Dean biopic might be a possibility down the road, Edwards says. (There’s never been one, although Martin Scorsese and “Goodfellas” screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi took a run at the idea in the late ‘90s.)

“Everything is on the table if it’s appropriate for the artist,” he says. “We’re looking at documentaries, we’re looking at biopics, we’re looking at musicals. We’re looking at lifestyle plays. Apparel. Beverages. Distilled spirits.”

And, yes, Edwards says, Dino will be on TikTok. “We get up every morning,” Edwards says, “and we think, ‘How are the next five years gonna look? Where do we want him to be seen? How do we want him to be defined within popular culture?”

By the turn of the 1960s, Martin and his Rat Pack cronies Frank Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr. had become the show-business avatars of a postwar America that swung and swaggered, the embodiment of the optimism of a country that felt poised to build Hiltons on the moon. Their live performances are the stuff of legend, in large part because practically none of what they did onstage would fly today — the drinking, the smoking, the machismo reasserted through misogynist and homophobic banter, Martin physically picking Davis up and saying “I’d like to thank the NAACP for this wonderful trophy.”

But back then, for audiences who’d never dream of puffing a joint or toting a picket sign, this was what rebellion looked like: Men in loosened bow ties, carousing without consequence or constraint. They were selling a dream of camaraderie and freedom that would captivate generations of guys who’d never be that lucky.

(Although lucky guys weren’t immune, either — speaking at Migos rapper Takeoff’s funeral in November, Drake revealed that since watching Dean on TV as a kid, he’d always wanted a Rat Pack of his own.)

McVie, who died on Wednesday, was the earthbound counterpoint to bandmate Stevie Nicks’ crystal visions, and the group’s most lovely and merciful presence.

It turned out people would gladly pay to watch Martin and his pals enjoy being famous in each other’s company. It’s a lesson Martin never forgot. At each stage of his remarkable run he seemed to shrug off a little more of the conceit and artifice of show business, leaning into the Zen of Dean, at peace in the spotlight, eyeballing cue cards he’s clearly never seen before with a What do we have here? smile — what his grandson Alexander Martin calls “that sliding-down-the-surface-of-things energy.”

Even by ‘70s standards, his weekly variety series “The Dean Martin Show,” which ran from 1965 through 1974 on NBC, plays like an artifact from a dead civilization — all cornball duets, Charles Nelson Reilly cameos and 1930s-style chorus girls in spangly lamé. But the show is liberated from vintage stiffness by Martin’s laid-back affect, an unrehearsed quality that he achieved by not rehearsing.

“It was definitely a show that used the idea that he wasn’t prepared,” says Bill Maher, who was a kid up past his bedtime in the late ‘60s when he discovered Martin. “There’s a spontaneity that comes with that, that’s irreplaceable. As stand-up comedians, we all know that anything that plays as an ad-lib is always remembered.”

Martin’s approach also anticipates the just-hanging-out-by-a-microphone vibe of your Fallons and Kimmels, of YouTube and livestreams and every other new medium that’s further blurred the line between performing and goofing around. Put it this way: It’s impossible to imagine Frank Sinatra’s podcast, but it’s pretty easy to imagine Dean’s, which would be worth it for the ad-read bloopers alone.

“That naturalism is very relevant to what celebrity is today — totally stripped-down, no artifice at all, I’m famous because I’m me,” Alexander Martin says. “He was authentic. The outros from his variety show, him sitting there with a drink in his hand — I could see watching that on my phone.”

Before Dean Martin was everywhere, he was Dino Paul Crocetti, born in 1917 and raised in Steubenville, Ohio, where he found his way to a singing career after logging hours as a shoeshine boy, a gas attendant, a steelworker, a bootlegger, a croupier and blackjack dealer, and — as “Kid Crochet” — a not-undistinguished welterweight boxer.

He first shared a bill with comic Jerry Lewis in 1946. After their respective sets, they’d close by fooling around onstage together. Soon this became the whole act — Jerry as an agent of chaos, disrupting Dean’s cool reserve. They were a red-hot nightclub draw, a hit on the radio, and over 10 years — while Martin’s solo recording career grew and grew — they made 16 films together, in which Martin, critic David Thomson wrote, “had only to sing the songs, kiss the female leads, and generally edge away from Lewis, as if next to an idiot in a line.”

In 1956, Martin walked away, leaving Lewis to seethe — they wouldn’t bury the hatchet until Dean showed up unannounced to Jerry’s annual muscular dystrophy telethon in 1976 — and made movies on his own. He starred alongside Sinatra for the first time as the diabetic gambler in Vincente Minelli’s “Some Came Running”; gunned down a Nazi played by Marlon Brando in “The Young Lions”; and held his own alongside John Wayne in “Rio Bravo,” as Dude, the town drunk who sobers up in time to help Wayne and Ricky Nelson fight off an army of outlaws. It might be his finest film performance, whether he’s trying to roll a cigarette with shaky hands (“What can a man do,” he asks Wayne, “with hands like that?”) or crooning “My Rifle, My Pony, and Me” with Nelson over the buildup to the final shootout. After that came more Westerns — if Martin longed to be anything other than Dean Martin, it was a cowboy — and films with the Rat Pack (including the original “Ocean’s 11,” a roaring Vegas vacation of a shoot that yielded a curiously dull movie) and a string of superspy spoofs with Martin as the proto-Austin Powers secret agent Matt Helm.

He claimed he’d stolen everything he knew about singing from Bing Crosby, but his supple delivery — the sound of bedroom eyes — anticipated Elvis Presley (particularly the Elvis of “Love Me Tender”) in ways that contemporaries like Perry Como didn’t. Martin laughed off the encroaching threat of rock ‘n’ roll like he did everything else. In June 1964, on ABC’s “The Hollywood Palace” variety show, he introduced an up-and-coming act called the Rolling Stones as “five singin’ boys from England who sold a lot of albums,” pronouncing the last word so it rhymes with “Valiums,” then adds, “They’re called the Rolling Stones. I’ve been rolled while I was stoned myself.” The Stones play a borderline-feral “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” then Dean comes back and says “The Rolling Stones — aren’t they great?” — and rolls his eyes all the way to the ceiling. (Bob Dylan wrote “Dean Martin should apologize t’ the Rolling Stones” in the liner notes to “Another Side of Bob Dylan” — but in July a Look magazine photographer would photograph him at home in Woodstock, smoking in a rocking chair, watching Dean on TV. And 37 years later, Dylan would record Martin’s 1958 hit “Return to Me” for the “Sopranos” episode where Jackie Jr. robs the poker game.)

Martin’s Stones intro could be a scene from a story about an unsuspecting star about to lose everything in a youthquake — except that by the end of that summer, Martin’s “Everybody Loves Somebody” would hit No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100, displacing the Beatles’ “A Hard Day’s Night.” The world may have been changing around Martin, but what did he care? There was always a new context in which to just be Dean. When “The Dean Martin Show” faded out in the mid-’70s, he distilled its sloshed energy into the Celebrity Roasts, where stars from Jimmy Stewart to Muhammad Ali dutifully showed up to let a jury of their peers give them the business. Nothing was sacred, not even Dean himself, who submitted to the royal treatment in 1976, grinning as the likes of Orson Welles, Joe Namath and Howard Cosell fired cue-card jabs at his heritage, his perceived mob ties, his boozing. Even U.S. senator and former presidential candidate Barry Goldwater got a few zingers off: “At my last re-election, Dean drank to my good health. He also drank to an armadillo.”

The drinking was a bit; Martin liked a cocktail now and then but the brown stuff he swilled onstage was Martinelli’s. He preferred afternoon golf to all-night revelry, once called the cops on a party at his own home when it raged too long, and was by all accounts hard-working and conscientious in his professional life. When his daughter Gail Martin started a singing career in her early 20s, he told her nothing was more important than showing up on time. “He said, ‘They pay us a lot of money to do something that comes fairly easily to us, so don’t make them look for you,’” Gail said in an interview. Still, he made a lovable fake drunk, and the act sustained him all the way to the ‘80s, when he played a Formula One driver in 1981’s “Cannonball Run,” starring Burt Reynolds, the most direct heir to Dean’s resolutely unserious approach to screen acting. He roped Sinatra into the sequel, 1984’s “Cannonball Run II,” and after that, he was basically done. His son Dean Paul, Alexander’s father, died in a plane crash in 1987; Martin cut short a reunion tour with Sinatra and Davis the following year. Sinatra would keep touring until three years before he died; Martin spent the last seven years of his life golfing, going to dinner and watching movies at home.

The best book about Martin —by virtue of being one of the best books ever written about any entertainer — is Nick Tosches’ “Dino: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams,” published in 1992. Martin was alive then, but did not participate. (“I won’t try to interview him,” Martin reportedly told an intermediary regarding Tosches, “if he doesn’t interview me.”) “Dino” is profane and exhaustive and brilliantly written, as spellbinding a chronicle of Martin’s time as it is of his life. It’s also a 569-page biography whose conclusion is that even the people closest to Martin barely knew him. It’s the story of a man who conquers world after world and gains only a deeper understanding of fame’s essential meaninglessness.

Tosches portrays Martin as an existential hero, and maybe there’s some truth to that. (Franz Kafka once said, “When lying on the floor one cannot fall,” but Dean Martin once said, “You’re not drunk if you can lie on the floor without holding on,” which is the same sentiment, only funnier.) At the end of the book, Martin has walked away from it all, having never needed any of it; Tosches leaves us with the image of Martin letting his final years slip away, watching Western movies on TV, as isolated as David Bowman in the white room from “2001” — but “content in a void,” his second wife, Jeanne, tells Tosches. “You would not learn anything from Dean,” she says on the book’s last page. “Quite honestly. He’s so distanced himself from his own past, his own life.”

But ask Gail Martin about Dean’s supposed unknowability, and you can practically hear her shrug through the phone: “I knew him,” she says. A very Dino answer.

“I think he just got tired of it,” she says of Martin’s decision to retire. “He wanted to enjoy his life — doing nothing, watching Westerns.”

Laura Lizer agrees. She’s now trustee of the Dean Martin Family Trust; she was Martin’s business manager as he wound down his career. She remembers a dinner in the ’80s, her and Dean and Dean’s agent, the agent telling Dean he’d been offered a return engagement at the London Palladium.

“He turned to me,” Lizer says, “and said, May I ask you a question? And I could tell by the way he said it that this was gonna be a serious question. And he said, ‘Do I have enough money to live the way I’m living and take care of my family the rest of my life?’ And I said, ‘Yes, sir — you do.’ And he turned back to his agent and said, ‘It’s my turn. My whole life, I’ve taken care of others, and it’s my turn to do what I wanna do.”

And as for how Dean might feel if he learned that some big-time company had paid a princely sum for the right to re-popularize his work, to put his name and face back out there, for Gen Alpha to discover? Lizer knows exactly how he’d react.

“He’d be laughing his pants off,” she said. “He’d be looking at me going, ‘Whaaat? My face? My name? Are you kidding?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.