A hip-hop sendoff like no other: How Thes One turned tragedy into an extraordinary album

- Share via

For 20 years, the Los Angeles hip-hop duo People Under the Stairs forged a career as independent artists that far exceeded anyone’s expectations, let alone its two members, Double K (Michael Turner) and Thes One (Christopher Portugal). Twelve albums, twice as many singles, hundreds of shows, and a fanbase that included everyone from the late Mac Miller and actor Bill Paxton to the writers on “The Simpsons.” Sitting inside the custom sound studio he built within the garage of his family’s home in the South Bay, Thes smiles wryly: “Our career arc was comically unbelievable.”

However, nothing is less hip in hip-hop than trying to navigate being a middle-aged rapper, and by early 2019, the pair decided it was time to retire on their own terms, releasing one final album, “Sincerely, The P.” Both men were still in their early 40s, happy to get off the tour treadmill to spend more time at home. Double K was recording new tracks while also contemplating a return to DJing parties and events. Thes had young children with whom he wanted to spend more time. Neither wrote off the possibility of still making music together, but barely two years later, the unthinkable happened.

On Jan. 30, 2021, Double K died in his sleep at his South-Central home. He was only 43, leaving behind his wife of 10 years, Etheldra, his mom, Tanya, and three siblings. Officially, his cause of death was alcohol poisoning, but while years of touring had taken its toll on both men’s bodies, nobody, not even Double K, knew how poor his health had become. “His death was a shock, even to him, I guarantee,” says Thes.

Understandably, his friend’s passing left Thes bereft. He locked up that home studio where the two men had spent countless hours over the years. “It was just too heavy to be in the room,” he explains. Left behind was a solo project Thes had started two years before, a series of compositions inspired by songs beloved by both men, especially Double K. That included nods to obscure yacht rock singles, underground disco jams and Double K’s absolute favorite: Parliament-Funkadelic. In his mourning though, Thes couldn’t bring himself to continue working on the project, citing survivor’s guilt: “It feels like you’re disrespecting the loss by just moving on with your life.”

Fans, politicians and even artists were complaining about Ticketmaster long before Taylor Swift filled stadiums. But experts say the anger may be misplaced.

It took Thes nearly a year to muster the will to reopen the studio, in part driven by other confrontations with mortality, including a near-fatal bout with COVID-19 in fall 2021 that coincided with his father’s cancer diagnosis (he’s currently in remission). For years, the People Under the Stairs, or PUTS, partners watched as artists had their catalogs exploited posthumously. After Detroit producer/rapper J Dilla died in 2006, Thes and Double K were dismayed to see a flood of Dilla’s unreleased tracks become packaged and circulated under dubious circumstances. When Thes realized his studio was filled with unfinished recordings by both he and Double K, a fear hit him: “I didn’t want this stuff sitting on a hard drive to be found and inaccurately pieced together.” That meant he’d have to complete them while he was still here.

By chance, at the same time, an old friend and longtime PUTS collaborator, keyboardist Kat O1O (Kat Ouano Mobley), got in touch to say she was coming to town from Hawaii. Kat had played on all the original 2019 sessions and with her coming back to L.A., Thes not only realized he had an opportunity to resume working on the project but something else clicked for him. “It all became so clear,” he remembers. “We’re gonna finish it for Mike, we’re gonna do it for him.” Thes One’s album, which comes out this week — the second anniversary of Double K’s passing — is fittingly entitled “Farewell, My Friend.”

Hip-hop artists have long paid homage to fallen colleagues — thanks to the sobering number of them who have been killed or died long before their time — but entire tribute albums aren’t as common in rap music as in other genres. The ones that do exist usually fall into one of two categories. There are albums that exhume and re-purpose previously recorded verses, like “The King & I” (2017), Faith Evans’ “duet” album with her late husband, the Notorious B.I.G., released 20 years after his shooting death in 1997. Then there are those assembled from vault material, like two (and counting) Pop Smoke albums, “Shoot for the Stars, Aim for the Moon” and “Faith,” which his manager and label put together from unfinished tracks after he was killed in 2020. Unsurprisingly, the Pop Smoke LPs earned the ire of some fans and reviewers who said it made “avaricious creative decisions” as part of an “obvious cash grab.” “Farewell, My Friend” conspicuously avoids any of these associations.

“A lot of people think this is going to be a vocal record, like me rapping about Mike or God forbid, using unreleased vocal takes from him,” says Thes, adding that when he was alive, “Mike was absolutely adamant he didn’t want any type of posthumous or vault stuff released.” While “Farewell, My Friend” includes the voices of both men, they are excerpts from interviews: no rhymes.

Instead, the album is primarily eight instrumental songs that form a “tone poem,” a reference to symphonic compositions like George Gershwin’s “An American in Paris” or Richard Strauss’ “Also sprach Zarathustra” that use long, narrative-like movements of changing moods and motifs. In the case of “Farewell, My Friend,” Thes purposefully conceived and sequenced the album “to tell the story of our life together,” from their early friendship, through their PUTS years, ending with Double K’s death and imagined afterlife. The album serves as an elegy, mixtape and soundtrack, all in one.

Though each track nods to older songs that held special meaning for the two of them, the compositions are neither conventional covers nor remixes. Sonically, they’re homages to their original source material while emotionally, they honor those pivotal moments of his and Double K’s lives. Album opener “Young Mike and Chris Floating Free” recaptures the moment the men first met by riffing on Level 42’s 1981 funk tune, “Starchild,” a single the two bonded over when they were digging for samples in local L.A. record stores back in the mid-’90s. “We were learning about music, learning how to dig,” Thes calls. “Mike thought this was some Bootsy [Collins] thing because it said ‘Starchild’ on it and he got home and was like ‘what the hell is this?’ Rookie mistake, but we ended up loving it.”

Several tracks later, “Mike and Chris Leave For Their First Tour” fast forwards to 1999 when PUTS performed in Japan for the first time. “That tour was monumental for us,” Thes says. “We were chasing that high for the rest of our lives.” His composition references one of the memorable musical discoveries they made while there, “It Ain’t No Big Thing,” a 1976 single produced by the legendary disco producer Patrick Adams.

“Farewell, My Friend’s” b-side is more somber. A short interlude titled “Prelude to Pain” leads into “The Bell Tolls for People Under the Stairs,” a melancholy reworking of “Love Theme From Spartacus” to mark the group’s decision to disband.

Then there’s the beautiful, devastating “Midnight January 30th, The Mothership comes for Mike.” The first part is based on a quirky Tiny Tim cover of Hal David/Burt Bacharach’s “What the World Needs Now,” but near the end, Thes abruptly shifts to a hissy recording from a video copy of Parliament-Funkadelic’s 1978 Flashlight tour. He shares, “it was [Double K’s] favorite concert and he would put it on to go to sleep. This was most likely the VHS tape that was playing that night he died in his sleep.” In the recording we hear George Clinton’s mothership land on stage, accompanied by the five-note theme from “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” You realize a beat later, it’s meant to mark the moment of Double K’s transition.

“Farewell, My Friend” is a coda on a creative partnership that winds its way back to 1996, when both men were still in high school; Double K at Hamilton, Thes a few miles away at Loyola. A chance meeting at Martin’s Records on Pico led to them listening to each other’s beat tapes in the front seat of a friend’s 1988 Corolla. Two years later, they began releasing records as People Under the Stairs. The name “felt funny and perfect,” says Thes. “We were not the cool kids.”

The duo joined a growing wave of local, independently minded rap artists that included the Freestyle Fellowship, Jurassic 5, Dilated Peoples and Madlib. Myka 9 of the Freestyle Fellowship, a group that PUTS revered as ”absolute gods” in Thes’ words, describes PUTS as “true pillars in the musical community” thanks to the “weight and integrity” of their performances; their approach to song craft was “high art yet low key.”

DJ Rhettmatic, of the long-standing turntable crew Beat Junkies, sees them through a different dichotomy, as “the underdogs of the underground hip-hop scene even though they have an international following,” a nod to how the group built a global fanbase despite lacking major label marketing and distribution muscle. Instead, PUTS handled all their own songwriting and production, navigated getting their records to retailers, and booked and managed their own tours. That DIY-ness came at a cost though, with hometown record stores and radio shows often shunning their releases. “All the gatekeepers tried to write us off,” Thes says. But “our outcast-ness defined us.”

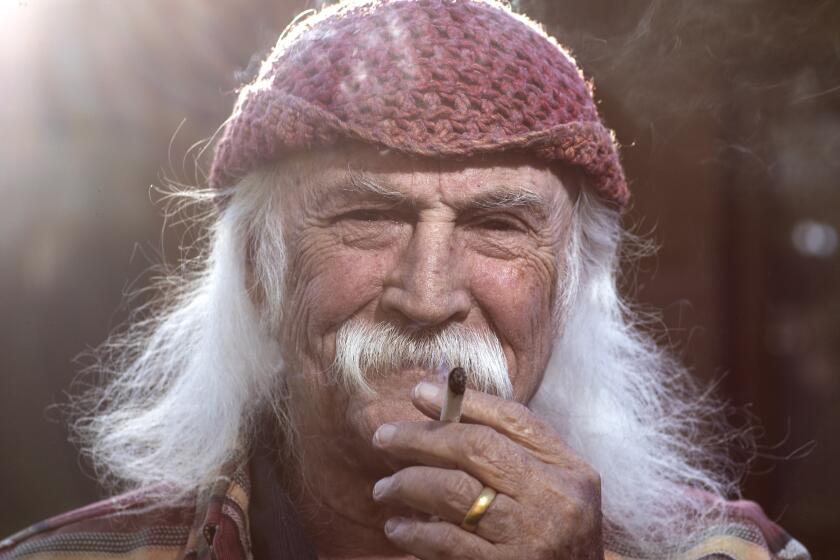

Crosby, who died on Wednesday, defined the contradictions of his era: He was voice of his generation’s ideals and, at times, its most pungent caricature.

Even as he and Double K agreed to sunset PUTS, it opened up new opportunities for Thes to work on his musical craft. For over 20 years, Thes had perfected a knack for finding samples and transforming them into hip-hop tracks. As a solo artist, the project that became “Farewell, My Friend” began as a challenge to himself to go further. “I wanted to see if I was capable of becoming a producer in the more traditional sense,” he says, nodding toward inspirations like Brian Wilson and David Axelrod, whose studio wizardry transformed the feel and texture of songs, albums, even entire musical styles.

Thes sought out storied studios around the Southland like 4th Street Recording in Santa Monica and 64 Sound in Highland Park, the latter being the last studio PUTS ever recorded in. Especially because he wanted to have Kat O1O play on acoustic pianos, he had learned from other engineers about how different spaces color the sound of instruments in unique ways. “There are newer studios that have these grand pianos and they sound like they look — shiny and big — but that’s not the sound we wanted,” he says. Instead, he went to 4th Street Recording partly because he knew “their piano had a lot of history to it.”

Even after Double K’s death, Thes and his collaborators felt their friend was still in the room with them. Kat O1O remembers how in some of the 2022 sessions, the instruments they were using would act erratically, sounding “horrible” one moment and then, as if by magic, would switch to “sounding really cool. We were like, ‘oh, that was Mikey.’ You’re here with us, we can feel you.”

As evinced by the four years it took to bring the album to fruition, “Farewell, My Friend” wasn’t easy to complete. “You know the closure that comes from releasing it and sharing it with the world? I wasn’t ready for any of that,” admits Thes. It took an intervention from his wife, Ritu, to push him forward. “It wasn’t just a traditional album that he was working on. It was this catharsis he needed,” she says, recalling how she told Thes, “you can wallow in despair or you can channel your energy into this project that will be healing for you and be a celebration of Mike.”

Fittingly, with the project finally done, Thes has found himself thinking about music and mourning in ways he’s heard others discuss but until now hadn’t experienced as personally.

“When we were on the road, people would come up to us and say, ‘your song got me through my father’s bout with cancer’ or whatever, but until you’re that person who’s using music to cope, that’s where you really feel how powerful it can be,” he says. “There might be other people, especially coming out of the pandemic, who are still struggling with the grief that a lot of people have dealt with … this may speak to them too. Just the sheer possibility of that makes me really happy.”

Oliver Wang is a Los Angeles-based writer and sociology professor at Cal State Long Beach.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.