A novel by Benjamín Labatut explores the dark side of science — and the color blue

- Share via

I’ve been dutifully checking out art and architecture while my colleagues in the features section have been consuming $295-per-person weed-infused dinners. I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and urban design columnist at the Los Angeles Times, back from vacation — and perhaps ready for a new beat?

Blue is the darkest color

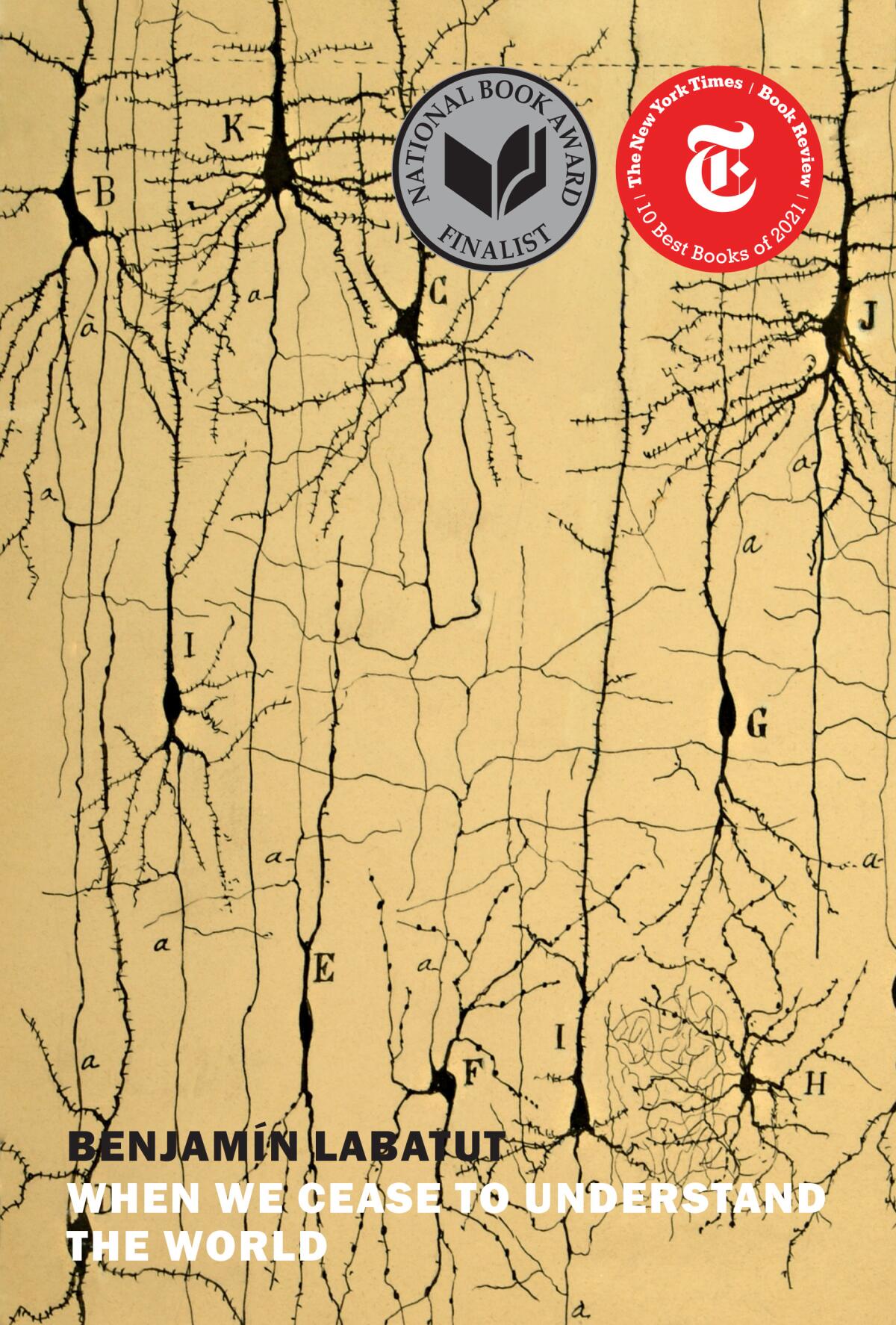

Blue has sent me down a rabbit hole. Specifically, Prussian blue, which appears as a silent, deadly character in Benjamín Labatut’s 2020 novel, “When We Cease to Understand the World.”

This slender volume — it is only 192 pages long — weaves together, in engrossing and disquieting ways, stories of scientific discovery. They are stories rife with obsession in the pursuit of knowledge but also the devastating ways in which that knowledge is ultimately deployed.

Hence, a chapter that takes the reader into the history of Prussian blue, the first modern synthetic pigment, created by Johann Jacob Diesbach in the early 18th century — which critically provided a stable source of blue for European artists at a time when blue pigments were wildly expensive and difficult to source. (These were generally derived from natural materials such as lapis lazuli, which had to be imported from Afghanistan.)

Prussian blue, also known as Berlin blue, after the city in which it was devised, makes its earliest known appearance in an early 18th century painting titled “The Entombment of Christ,” by Adriaen or Pieter van der Werff — in which the Virgin Mary’s luminous blue mantle catches the eye amid a palette of earthier, fleshier tones. (The painting’s attributions vary depending on the source, likely because the Van Der Werffs were brothers, with Pieter working in Adriaen’s studio, where he often made copies of existing works. As a result, different versions of this scene, under Adriaen’s name, appear in different European collections. In his novel, Labatut attributes the work to Pieter.)

Regardless of who painted what, by the 19th century, Prussian blue had developed an artistic fan base as far away as Japan, where artists such as Hokusai used it in landscape prints such as his iconic “Great Wave Off Kanagawa.” (The version seen above is from the permanent collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.)

And that’s just the beginning of the story for Prussian blue. Because when it’s combined with diluted sulfuric acid, it turns into hydrogen cyanide, otherwise known as cyanide, one of the deadliest poisons known to man. (“Cyan” is a reference to its origin as a blue pigment.) It is one of humanity’s more devastating inventions — a commercial version of cyanide, Zyklon B, was deployed by the Nazis in their genocide chambers.

Prussian blue, writes Labatut, is “the blue that shines not only in Van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’ and in the water of Hokusai’s ‘Great Wave,’ but also on the uniforms of the infantrymen of the Prussian army, as though something in the colour’s chemical structure involved violence: a fault, a shadow, an existential station passed down from those experiments in which the alchemist dismembered living animals to create it, assembling their broken bodies in dreadful chimeras.”

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“When We Cease to Understand the World” is inspired by scientific history, but it is not a straight historical account. It is a novel. And if at first it reads like a collection of essays about the history of science, as the book progresses, it expands into more metaphysical and mystical spaces — all of which are ultimately woven together with the appearance of a mysterious character called “the night gardener.”

Critic John Banville, in the Guardian, described the book as a “nonfiction novel.” I think of it more as a dramatization, in novel form, inspired by real events. However you choose to categorize it, the book functions as a series of linked meditations on the nature of discovery and what it means to confront that which we do not — and cannot — know. Over five spare but poetic chapters, Labatut covers color and mass death. He also writes about the singularity and black holes, along with the scientists who aimed to quantify these phenomena.

Labatut, a Chilean writer of Dutch descent, originally published the novel in Spanish in 2020 as “Un Verdor Terrible.” Last fall, New York Review Books released an English-language translation by Adrian Nathan West. It quickly materialized on former President Obama’s list of summer reads. It was also shortlisted for the International Booker Prize and the National Book Award for Translated Literature.

I’ll confess that I knew little about Labatut or the book when I picked it up shortly before going on vacation. It was an impulse buy: I was intrigued by its scientific inspirations and the odd, diagrammatic nature of the cover. But I quickly found myself engrossed by the story it presents — of men who compulsively race to decode the workings of nature only to face chaos, violence and uncertainty.

We look to science for answers, but sometimes all we find is ourselves.

Art post-Roe

“A living moment in time — the present of 1962, when civil rights movements were churning and change from the insulated, socially repressive postwar years seemed possible — is embodied in a work of art that gives form to the callous violence routinely done to desperate women.” That’s Times art critic Christopher Knight writing about Edward Kienholz’s 1962 sculpture, “The Illegal Operation,” an unblinking examination of a back alley abortion currently on view at LACMA.

Kienholz’s work serves as poignant prequel to a show of work by Andrea Bowers at the Hammer Museum. The L.A.-based artist has long made works that touch on issues such as the environment and women’s bodily autonomy. “Bowers’ works typically create a vivifying tautness between the individual and the group,” writes Knight in his review. “I think of her as the E pluribus unum artist, making the national motto — out of many, one — visually and materially manifest.”

Bowers’ show opened right as the Supreme Court was overturning Roe vs. Wade. “It felt like somebody dropped a giant boulder on my body,” Bowers tells contributor Catherine Womack, in a profile. “There was this deep sadness in my heart. I didn’t want to have the opening. All I could think about were ... all the risks they took, generations of hard work by activists erased.” But in Bowers’ work, says curator Connie Butler, is an important lesson for the moment: “There is a feeling of persistence there.”

Times metro columnist Gustavo Arellano has a fascinating story about memorials to aborted fetuses. One of the oldest is right in Boyle Heights.

And Mexico City correspondent Leila Miller reports on how the green bandanna became a symbol of the abortion rights movement — one that originated in Latin America.

Visual arts

I recently hung out with artist Mercedes Dorame, who took me to see a Tongva bedrock mortar in Topanga Canyon. This historic tool appears at the heart of a 2013 photograph by the artist, “Well of Moon and Sky — Kotuumot Kehaay,” that is on view at the Huntington. The image — which also features various ephemeral interventions by the artist — is helping reframe what gets defined as American in the museum’s permanent collection galleries. “My intervention, why I make things myself, why I have my hand in it,” Dorame tells me, “it’s because it also reiterates: I’m Tongva. I’m here. I’m making now.”

The photos for this story, taken by Times photograph Robert Gauthier, are phenomenal.

At La Plaza de Cultura y Artes, Hyperallergic contributor Matt Stromberg looks at an exhibition of Chicano art that avoids the greatest hits in favor of showing prominent artists of the ’70s and ’80s “experimenting with both medium and message.”

Classical notes

The L.A. Phil is marking the 40th anniversary of the Green Umbrella concert series devoted to new music. And a recent performance took the series to a new location: the Ford. The show, reports Times classical music critic Mark Swed, opened with Gérard Griseys’ “Stèle,” a work framed by a pair of bass drums on opposite sides of the stage. “What followed was one different kind of music after another,” writes Swed, “each entering into an interplay with the not always benign environment.”

The New York Times profiles Yuval Sharon, co-founder of the experimental L.A. opera company the Industry. Sharon is now also serving as artistic director of Michigan Opera Theater (which has been renamed Detroit Opera). “Nearly two years into his five-year contract,” writes Mark Binelli, “Sharon has already radically elevated Detroit Opera’s status in the larger cultural ecosystem.” In the process, he has sought to make opera that is radically of Detroit.

On and off the stage

A musical about a musical about a husband who has his wife killed while having an affair with a prominent radio personality? That’s the premise of Matt Schatz’s “A Wicked Soul in Cherry Hill,” which is receiving its world premiere at the Geffen Playhouse. All of it was inspired by the true story of a New Jersey rabbi who had his wife murdered in 1994. Times theater critic Charles McNulty is of mixed mind on the production: “Treated as a purely fictional story, the musical is a delight,” he writes. “But a woman was murdered, a family shattered and a community left reeling. Should I really be chuckling over the droll lyrics of kibitzing bystanders?”

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The six-minute showstopper that opens the second act of the stage adaptation of “Moulin Rouge!” has become a viral sensation on TikTok, with users replicating the wild routine — which includes the entire cast dancing as they belt out hits by Lady Gaga, Britney Spears, Soft Cell, the White Stripes and Eurythmics. The Times’ Ashley Lee looks at how “the best Act 2 opener in recent memory” came to be.

When the play “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child” premiered in London in 2016, it was a two-part affair, with a running time of more than five hours that required two separate tickets. The version opening at San Francisco’s Curran Theatre is a more focused 3½ hours. Lee gives the plays’ different versions a line-by-line look: “Without so much gratuitous small talk, lackluster punchlines and ineffective jabs, whatever has survived the cut is much more impactful than before.”

The parody musical “The Streaming-Verse of Madness: An Unauthorized Musical Parody” brought comic Aidan Park back to one of his early loves: musical theater. As he tells The Times’ Steven Vargas, this move has everything to do with finding more intriguing roles to choose from on the dramatic stage. Frequently typecast, he said he once did nine productions of “Miss Saigon” because “I’m an Asian guy who can sing.”

Essential happenings

Matt Cooper has the nine best picks for the weekend, including the annual free Shakespeare festival in Griffith Park and a site-specific outdoor staging of Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Tony-winning “Into the Woods” at Descanso Gardens.

While I was on vacation, I caught “Persia: Ancient Iran and the Classical World” at the Getty Villa. The show features some truly exquisite pieces, including incredible mosaics of archers and sphinxes made from glazed brick, and a pristine stone tablet bearing inscriptions in three languages. The show is in its final weeks (it closes on Aug. 8). You can read Christopher Knight’s review of the show and see one of those mosaics right here.

Plus, CicLAvia is going down in South L.A. this Sunday!

Moves

Jacqueline Stewart has been named the new director and president of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Currently serving as the museum’s chief artistic and programming officer, she succeeds Bill Kramer, who last week was named chief executive of the larger Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Guggenheim director Richard Armstrong is departing the museum after 14 years.

Passages

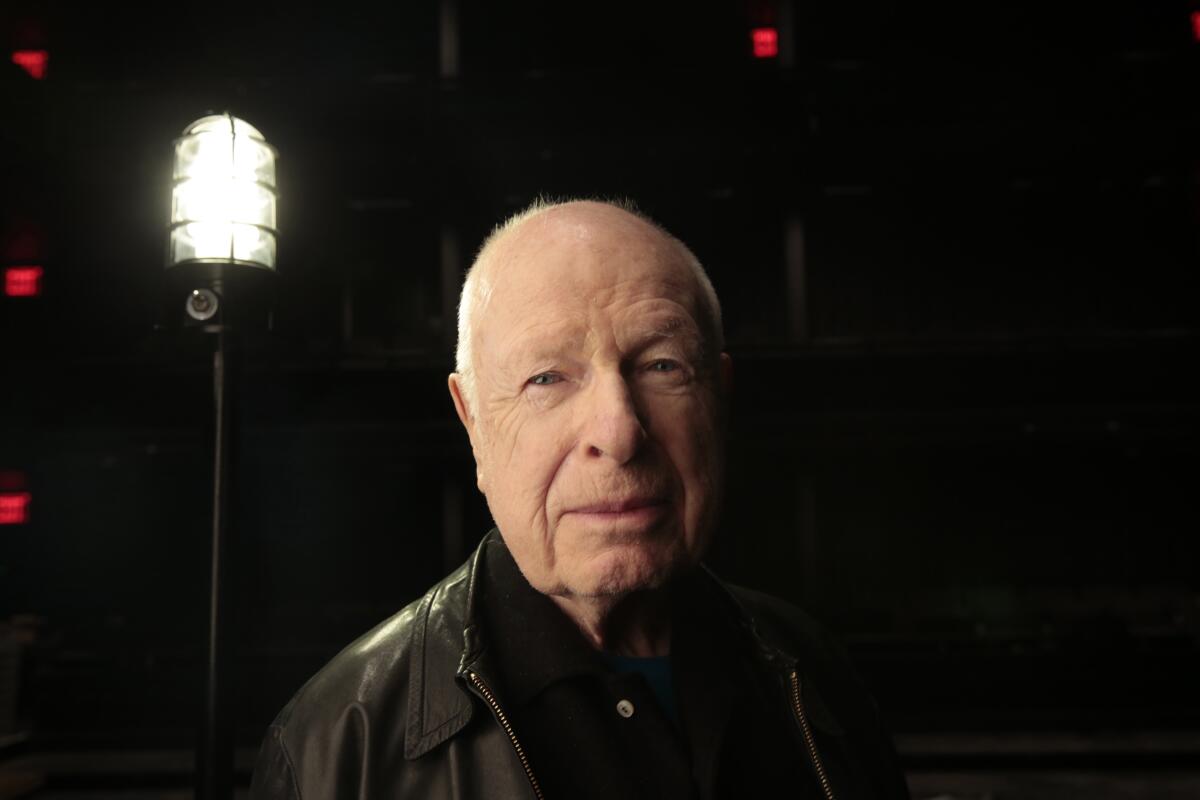

Peter Brook, a Tony Award-winning British director who helmed innovative productions of works by Shakespeare, Beckett, Chekhov and Shaw, as well as a nine-hour adaptation of “The Mahabharata,” has died at the age of 97. In a tribute, Charles McNulty writes that this was a director who never rested on his laurels: “Brook lived and worked in a continual state of becoming. Even in his last decades, when he might have basked in the eminence of his international reputation, he was still experimenting, still trying to separate the essential from the meretricious.”

Tony Award-winning producer Steve Fickinger, whose credits include “Dear Evan Hansen,” currently on view at the Ahmanson Theatre, died last month at the age of 62.

Marcus Fairs, the founder of the influential design site Dezeen, has died at 54.

In other news

— ArtCenter faculty have voted to unionize with the California branch of the American Federation of Teachers.

— “Chroma,” an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, features reconstructions of classical statuary as they would have been rendered at the time of their creation: bathed in color.

— A mysterious Georgia monument — intended to guide Americans in the wake of an apocalypse — is destroyed by vandals.

— I’m addicted to the dystopian nightmare that is Apple TV+’s “Severance.” Curbed’s Diana Budds looks at the show’s creepiest set piece: Eero Saarinen’s 1962 Bell Labs.

— Rotterdam will not be dismantling a 95-year-old bridge to let in Jeff Bezos’ superyacht.

— Former President Obama spoke at the annual American Institute of Architects conference and called out liberal NIMBYs for opposing affordable housing.

— In Evanston, Ill., a small Restorative Housing Fund is helping Black residents buy or maintain their properties as part of a reparations commitment.

— And, in Mexico City, an intriguing program called PILARES is getting high-profile architects to design public buildings in underserved communities.

— L.A.’s Crosswalk Collective paints crosswalks guerrilla-style at locations with high numbers of accidents.

— Refugee dancers from Ukraine have formed their own dance company, the United Ukrainian Ballet, in The Hague.

And last but not least ...

In advance of Boris Johnson’s resignation, the wax figure of the prime minister by Madame Tussauds appeared outside a jobs center in Blackpool. Now that is some winning curation.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.