Hammer Museum’s intimate expansion punctures the myth of the ‘flexible’ museum space

- Share via

It’s Fat Bear Week and I’m team Chunk! I’m Carolina A. Miranda, art and design columnist with the Los Angeles Times, and I’m here with all the voluptuous ursidae and essential arts news:

A smart expansion at the Hammer

It’s a big week at the Hammer Museum: The sixth edition of the splashy “Made in L.A.” biennial has landed and it’s the first to be staged since the museum completed a two-decade, $90-million renovation and expansion that, over time, has added galleries at different scales, a state-of-the-art drawing center, a refreshed courtyard and renewed back-of-house spaces. (My colleague Deborah Vankin wrote about the revamp when it opened in March.) A particularly elegant touch: the staircase that zigzags dramatically between the museum’s administrative floors.

The expansion, part of an evolving master plan devised by Michael Maltzan Architecture in the early 2000s with the museum’s director, Ann Philbin, has been about taking a scalpel to a structure that, since the beginning, has felt more like a Late Modern bunker than a public museum. The original building, designed by Edward Larabee Barnes, was essentially a horizontal box banded in black and white marble, attached to the base of the old Occidental Petroleum Tower (now owned by UCLA)

Upon its debut in 1990, Times art critic William Wilson described it as “too aggressive.” It was certainly off-putting — giving little more than blank façades to the city around it. Over the years, Maltzan says he’s encountered people who thought it was the parking garage for the tower. “There was no sense that the museum was here.”

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Over the last two decades, Maltzan’s firm has skillfully sculpted this ungainly complex.

Entrances have been made more prominent and gallery ceilings raised. A dull auditorium was transformed into the more welcoming (and lightly glamorous) Billy Wilder Theater. An unfinished black-box space next to the theater was turned into a studio/lecture/performance space and windows were added to admit daylight. A bridge added to the second level in 2014 better connected galleries on one side of an outdoor courtyard to galleries on the other. (I like to call it the bridge of tears of L.A. Times employees, since it was funded, in part, by our disastrous former owner Sam Zell.)

A more recent addition has been a fantastic 3,100-square-foot gallery devoted to works on paper on the third floor, which opened last year. And this spring, the museum opened a highly idiosyncratic exhibition hall for contemporary art: an old bank space on the eastern end of the building that remains in a very raw state. The vault is still visible, the floors are a rough combination of concrete and terrazzo and patches of the drop ceiling are missing. Reaching it requires a circuitous route: either out onto Wilshire or via an elevator that deposits you into the very corporate lobby of the Occidental tower and on to the bank space beyond.

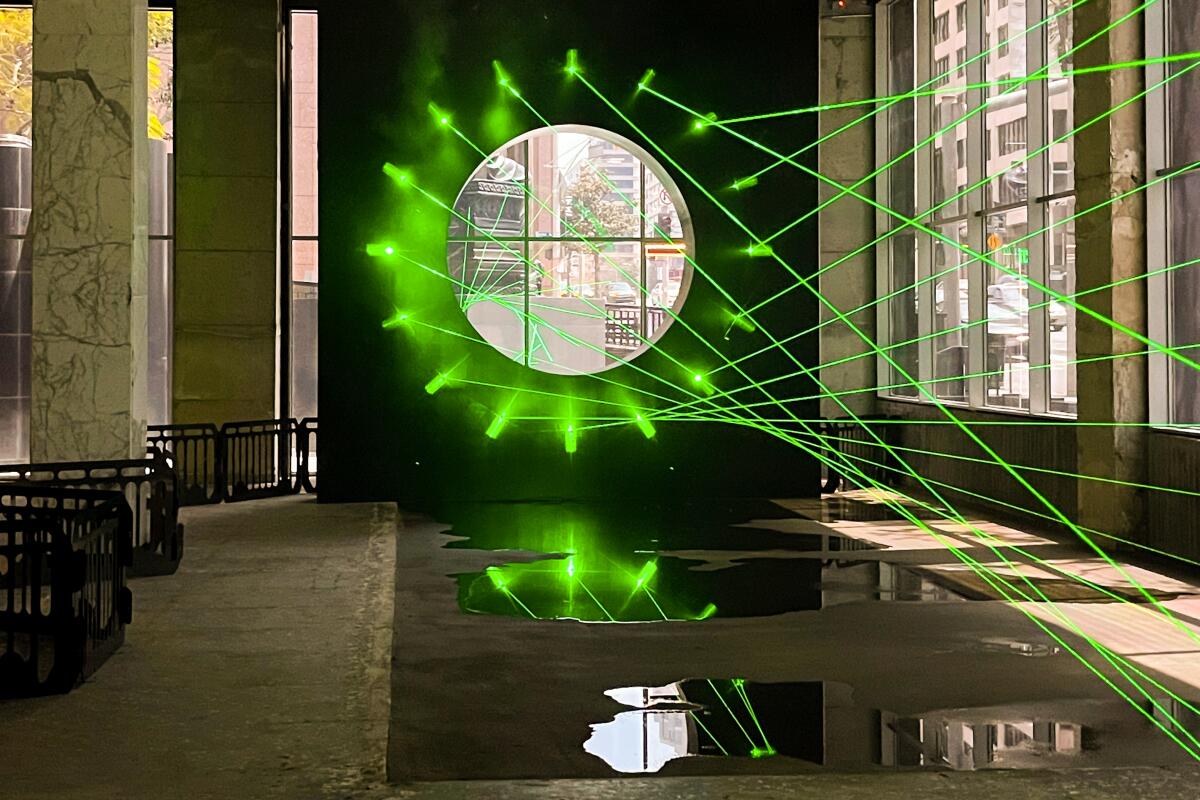

Finding the gallery is akin to locating a speakeasy — and the current installation, by Rita McBride, a series of neon green lasers and and puffs of mist, makes it feel as if you’ve wandered into some secret lab.

I am into the variety. But it is the works-on-paper gallery, above all, that has seduced me since it opened last year.

Diminutive cut-paper pieces by Picasso and studies by op-art painter Bridget Riley, which might have been swallowed up by a room at any other scale, popped with a sense of immediacy in recent shows. Currently occupying the gallery is an ongoing exhibition of work by Van Leo, a dashing Armenian Egyptian studio photographer who first rose to prominence in the 1940s. One display area is covered in wallpaper inspired by the decor of a Cairo home that was formative to Leo as a young man. The gallery is an institutional space that, because of its human scale, can also feel personal.

The Hammer’s mix of exhibition spaces has lately had me reflecting on the nature of museum galleries.

One of the buzz phrases in museum architecture in recent years has been “flexible space.” Often, this has translated to cavernous galleries divvied up by temporary display walls. Except those temporary walls end up becoming semipermanent, because temporary walls in Southern California have to be engineered to seismic code — which makes them onerous to install.

It would explain why purportedly “flexible” galleries at museums like the Broad and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (specifically the Resnick Pavilion) have had an unchanging layout for years. The Orange County Museum of Art, which opened late last year, has a similar type of space. And I’m willing to put money down on the fact that the “temporary” walls in their “flexible” gallery space will not be rearranged anytime soon.

This phenomenon has led to a whole lot of sameness across museum design — an aesthetic with a whiff of art fair. It also doesn’t do any favors to the art. Small vintage photographs and tiny drawings simply get lost in a room with 20-foot ceilings. “Bigness,” says Maltzan, “is different from flexibility.”

The Hammer has done it right, developing a series of singular spaces that provide experiences geared to specific types of art. Moreover, the plan has found ways to adapt an old building to new uses.

One of the installations I relished in the current biennial was by the Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (which Vankin wrote about last week). The artists affiliated with the archive have turned a small room near the bank gallery in the petroleum tower lobby into an anodyne-looking employee break room, complete with industrial coffee maker. There is also a snack machine, though look closely and you’ll find that it is stocked with art. Tucked into some of the counters are additional displays.

It’s a case of prankish artists undermining the corporate aesthetic of the architecture — and the sort of conceptual piece that would get lost in a blank, “flexible” space.

In and out of the galleries

Since we’re on the subject of the Hammer: Times art critic Christopher Knight reports that the biennial, organized by curators Diana Nawi and Pablo José Ramírez, “offers material, flesh-and-blood presence in place of ubiquitous camera pictures, both analog and digital, or their standard Conceptual art kin.” Knight parses an exhibition in which much of the work on display was shaped by the isolation and turmoil of the pandemic.

An intriguing story within the biennial is that of sculptor Luis Bermudez, who died in 2021 at age 68. His ceramic pieces — inspired by pre-Columbian mythology and the Mexican landscape — are a prominent feature within the show. The display brings critical attention to an L.A. artist who remained under the radar of the art world, writes contributor Renée Reizman.

My colleague Steven Vargas has a story about AMBOS, the art collective founded by Tanya Aguiñiga, which addresses issues of immigration at the border through craft. The group has created an installation for the biennial that engaged students in a ceramics program in Tijuana as well as artists in Los Angeles.

Separately, I interviewed artist Alexandre Arrechea, currently the subject of a solo show at MOLAA, about how his work is motivated by architecture and its meanings. (I really appreciate the way the show’s installation challenges the neutrality of the plinth.) We also discuss the set design he did for a Black Sabbath-inspired ballet in England — which features a real-deal demon!

I had a peek at a new study by the advocacy group Museums Moving Forward that offers a qualitative look at workplace culture in U.S. museums. Participation from L.A. institutions was weak. (I’m lookin’ at you, Getty, LACMA, Hammer, MOCA.) But the study is helpful in outlining how issues such as burnout and low wages are leading to an unsustainable level of turnover in this sector. The bottom line: Museum funding structures and patronage need to evolve.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The second season of the Getty’s “Recording Artists” podcast has just landed, with episodes devoted to Marcel Duchamp, Frida Kahlo and Nam June Paik.

On and off the stage

Times theater critic Charles McNulty is in New York, where he just had a look at Annie Baker‘s latest play, “Infinite Life.” Baker, like Chekhov, he writes, likes to test the need for propulsive action with a story that focuses on five women and a man whose circumstances are revealed through the ailments they bring to a fasting clinic in California.

McNulty also took in the revival of “Purlie Victorious: A Non-Confederate Romp Through the Cotton Patch,” a 1961 satire by Ossie Davis that later served as the basis for a film and a musical. Kenny Leon is directing a new production at the Music Box and it is, writes McNulty, “built for speed and farcical flamboyance.”

Essential happenings

Steven Vargas has all the best L.A. events in his weekly newsletter, including a solo show by painter Ludovic Nkoth at François Ghebaly.

I am a latecomer to “Hadestown,” the Tony-winning Broadway musical that sets the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice in New Orleans. Charles McNulty described a touring production as “mesmerizing” when it landed in L.A. in 2022. The show is back at the Music Center with a different cast — and while I can’t compare it to the original, I will say that I found myself moved and absorbed by the retelling of this timeless story. You’ve got ’til Oct. 15 to see it.

Moves

The new class of MacArthur Fellows has been announced. It includes artist and composer Raven Chacon, composer Courtney Bryan, multimedia artists María Magdalena Campos-Pons and Dyani White Hawk, and novelist and short-story writer Manuel Muñoz (whom I had the great pleasure of profiling last year). Find the full list of MacArthur Fellows at this link.

The National Latinx Theater Initiative, spearheaded by the L.A.-based Latino Theater Company, will supply $9 million in grants to 52 Latino theaters in cities around the U.S. and Puerto Rico. The initiative was made possible thanks to a $5 million grant from the Mellon Foundation.

UC Irvine’s Langson Institute and Museum of California Art has added works to its collection by Matt Mullican, Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle and Julius Shulman.

Passages

Rudy Perez, a groundbreaking choreographer who was a pioneer of ’60s-era postmodern dance, has died at 93. “Perez’s minimalist but wildly experimental work, marked by spare, precise movements,” writes Deborah Vankin in an obituary, “helped ignite a budding Los Angeles dance scene after he moved west from New York in the late 1970s.”

In the news

— You’ve heard of clickbait. At its heart lies discourse bait. Vox’s Rebecca Jennings explains.

— Recur, the NFT startup backed by Museum of Modern Art trustee Steve Cohen, has gone belly up.

— GOP congressmen have been attacking the Smithsonian Museum of the American Latino over a show devoted to Latino civil rights.

— The Azerbaijani invasion of Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh is putting important Armenian monuments at risk.

— Peter Zumthor is doing some Pritzker-level bellyaching over how his design for LACMA is turning out.

— The story of Frank Gehry and Disney Hall is told in this beautifully executed multimedia piece by the Getty.

— The Catalina Museum for Art & History is marking 70 years with a show of rare objects from its collection.

— I’m all for this episode of 99% Invisible about the Satanic Panic.

And last but not least ...

One word: cake.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.