Woodstock glorified them. Tarantino barbecued them. In 2019, whither the hippie?

- Share via

Promoter Michael Lang’s Woodstock 50 festival didn’t pan out, and maybe that’s just as well. “Civil War re-enactors in everything but name” was one Facebook wag’s joke about its prospective attendees back when the whole retro shindig was set to kick off in Watkins Glen, N.Y., on Friday. Then Watkins Glen pulled out, leaving Lang — the original Woodstock’s brashest impresario, still milking the brand at age 74 — scrambling for an alternative site.

Eventually, he found one: Maryland’s upscale Merriweather Post Pavilion, not the likeliest venue for commemorating three bucolic, long-gone days of unruly free love, unruly free music and unreliable acid. By then, however, the event’s announced headliners, from newbies like Miley Cyrus to Yasgur’s Farm O.G.s like Country Joe McDonald, were bailing right and left. Reluctantly bowing to reality, because there’s a first time for everything, Lang pulled the plug two weeks ago on the presumably final facsimile of his generation’s finest (or were they?) 72 hours.

Every facsimile has a simile hidden in it somewhere. Lang’s futile search for a home for his graybeard reprise nicely mimicked how unsettled hippiedom’s legacy still is. Part of the confusion is that too many people still conflate hippie values — good old American transcendentalism in scruffy, hedonistic “Do your own thing” disguise, more or less, and political mainly in its anti-materialism — with New Left political activism, which any aging New Leftist could tell you wasn’t the case. The Yippies, radical prankster Abbie Hoffman and satirist Paul Krassner’s attempt to amalgamate the two, were always more of a stunt than a movement.

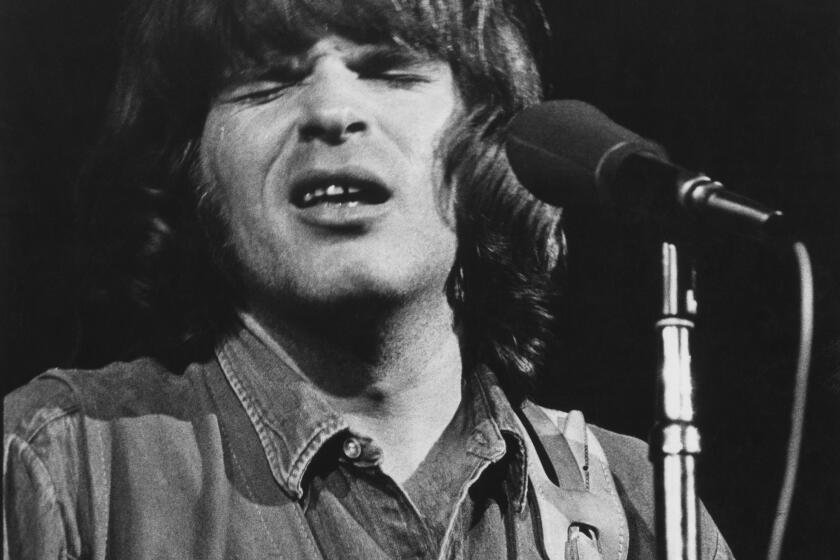

Fifty years ago, Creedence Clearwater Revival was forced to follow a “drugged-out” Grateful Dead at Woodstock, resulting in a set they didn’t want memorialized... until now.

In the Trump era, which is in so many ways the culmination of rancor first unleashed in the 1960s, the Yippies’ fusion of antic jokes and dead-serious protest looks prescient. That doesn’t really tell us much about the larger “legacy” question, though. Half a century later, nobody can say for sure whether the hippies — and what they represented — are just desiccated history, a useful Pied Piper cautionary tale for idealists uninterested in how the world really works, or a benign influence now permanently ensconced in our culture, from relaxed sexual mores, sartorial freedom and legal marijuana to, er, self-help guru Marianne Williamson running for president and making that seem not totally implausible.

Maybe posterity’s uncertainty about what to make of hippies is what those hairy freaks deserve for exalting vagueness so damned much. In any case, the only jury whose verdict particularly matters seemingly couldn’t care less. Millennials have no use for anything associated with the boomers they blame for the crummy — well, it is — world they’re stuck living in, which was pretty much how the boomers felt about the World War II generation. Scorn for precedent is the most venerable youth-culture tradition of them all, making hippies irrelevant as either forebears or entertaining objects of ridicule to anyone under 30. (Hey, didn’t boomers used to have a saying about that? Something about “Don’t trust ... ,” um, anyone as old as they are now.)

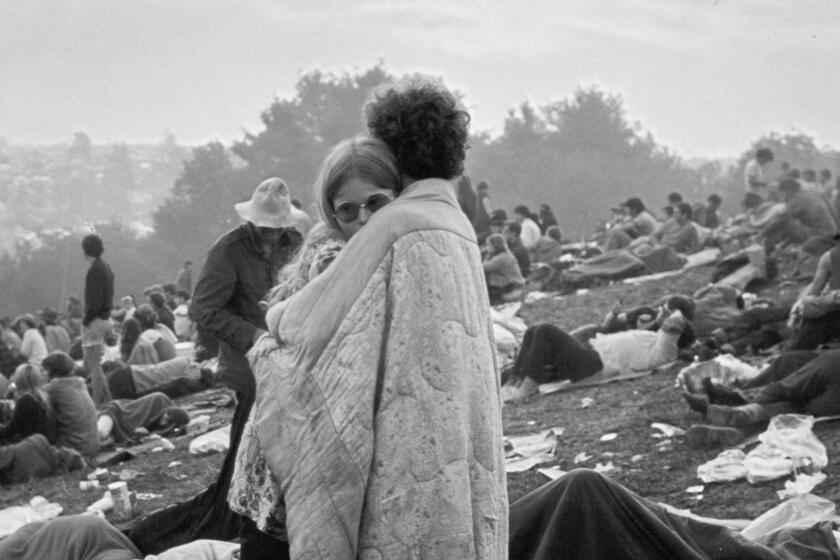

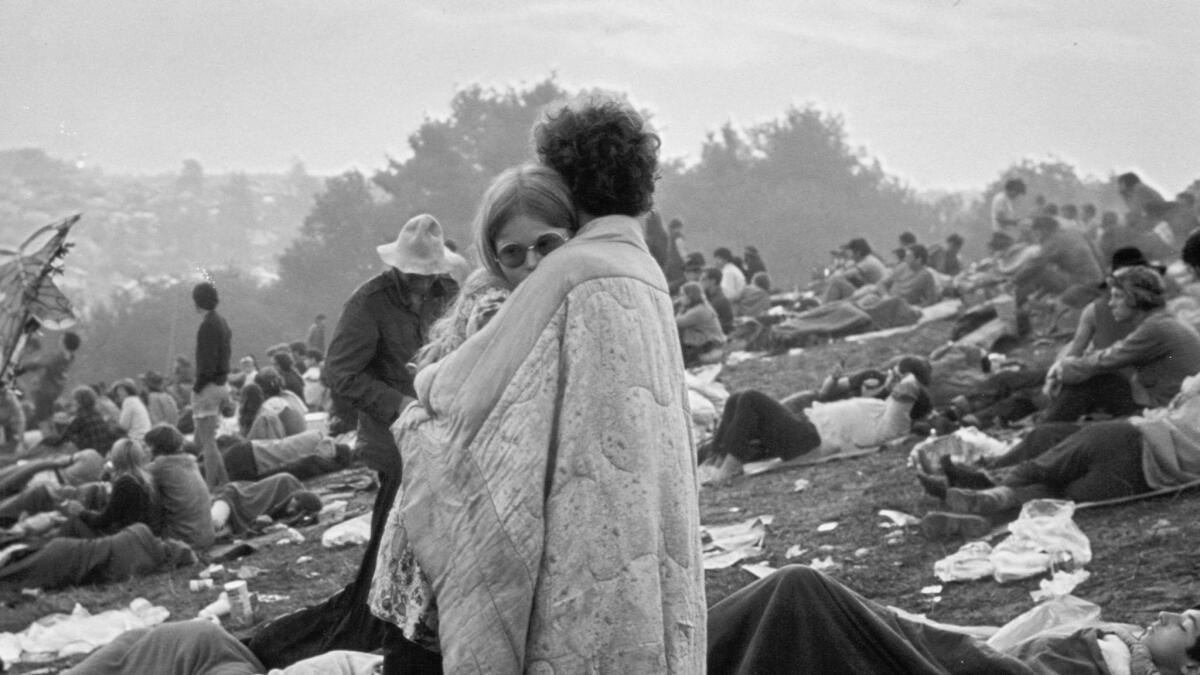

Still, perhaps the only valid question to ask any 1960s hippie of his or her bygone lifestyle choice is: Did it make you happy? Did it change your life for better or worse? Whether they were famous or not back then, too many members of the “for worse” contingent are in cemeteries, thanks to drugs and other forms of premature oblivion. Beth Ann Simon, who died in the East Village in 1966 at age 23 because of her obsession with a rigorously macrobiotic diet, may have been hippiedom’s true Patient Zero. But Nick and Bobbi Ercoline, the unutterably moving couple embracing at the dawn of the Age of Aquarius in the cover photo of the “Woodstock” soundtrack album, are still together and happily married 50 years later. It would be rash to wonder if “failure” is even part of the Ercolines’ vocabulary.

Fifty years on, America remains obsessed with Woodstock. Here are the best recordings, movies and books to accompany your weekend nostalgia trip.

Whether we were alive in 1969 or just imbibed the myths years or decades later, the rest of us are dealing with a reckoning this month. Not only is the 50th anniversary edition of the original Woodstock documentary back in theaters nationwide, but here in L.A., at least, virtually every multiplex screening it is also showing “Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood,” Quentin Tarantino’s revisionist riff on the darkest chapter of the whole hippie saga: the Tate-LaBianca murders committed by Charles Manson’s scraggly followers less than a week before the original Woodstock got underway.

Woodstock: the media construct

Because feckless but sweet peace-and-love quietism seldom makes going on a killing spree look like the obvious next step, equating the Manson “family” with hippies in general is obviously a fallacy. However, so is treating “Woodstock” and “hippies” as if they’re synonymous. Haight-Ashbury’s denizens had staged a mock funeral for their shaggy subculture soon after the Summer of Love alerted the rest of the country to the hippie phenomenon and the Monterey Pop Festival signaled its looming conversion into cultural specie. If you’re going to be a purist about it, which they certainly were, those self-appointed undertakers weren’t wrong. “Hair,” a.k.a. “The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical,” premiered at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater that October, and we all know what it means once musicals want in on the action.

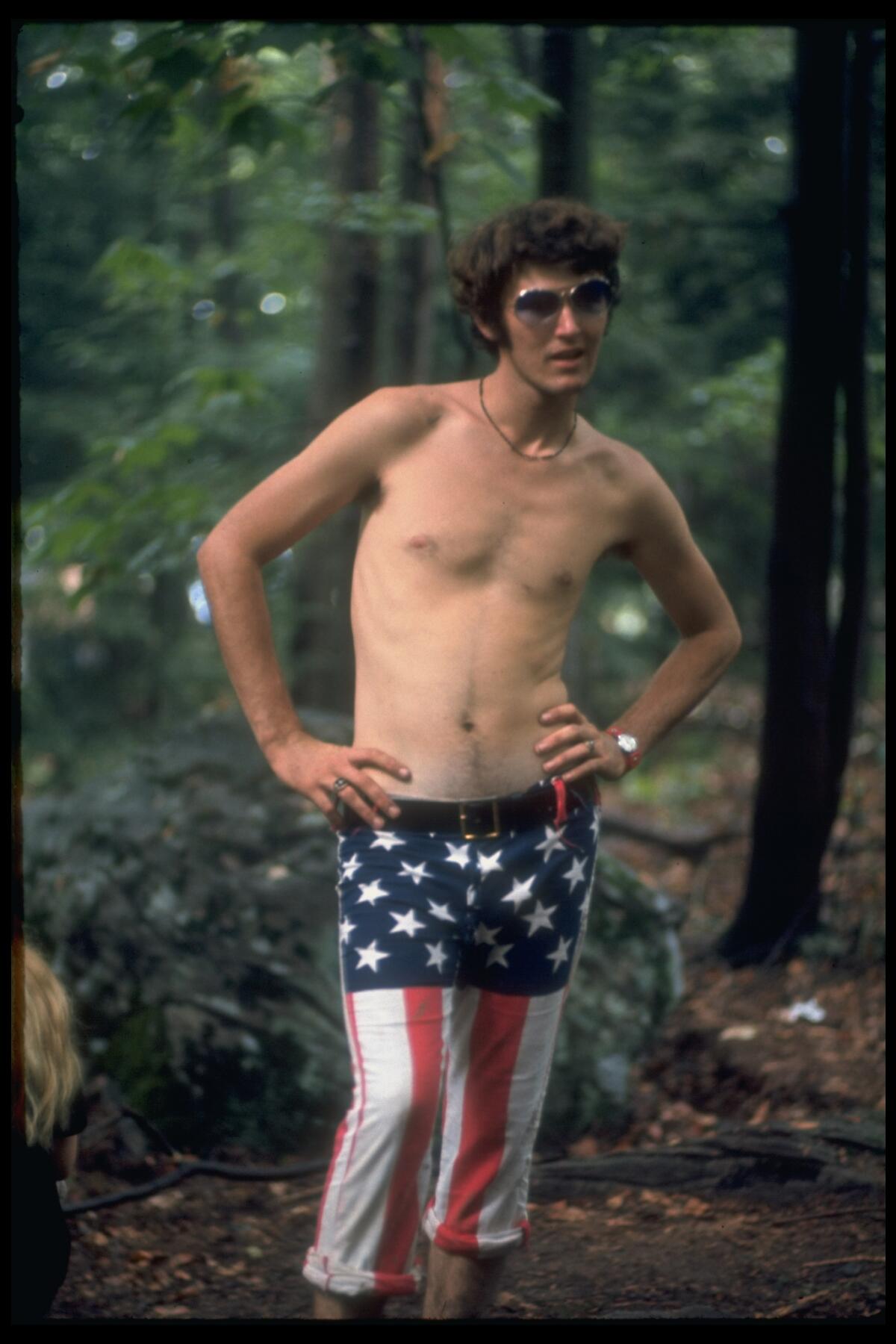

By and large, the half-million unwitting movie extras who packed Max Yasgur’s farm in August of 1969 belonged to something more amorphous and, in the long run, less committed: the counterculture, which appropriated a plethora of hippieland’s habits and attitudes. It just didn’t require its participants to prove their bona fides by doing anything crazy like dropping out of college to go live in San Francisco crash pads or hardscrabble rural communes full-time. The result was what critic Robert Christgau later termed “that unprecedented and probably unsustainable contradiction in terms, mass bohemia.”

The distinction scarcely mattered to the country at large. As far as a bemused America was concerned, Lang’s festival was its first and biggest vicarious encounter with hippieland in action at its most benignly blissed-out. But the key word here is “vicarious.” From pretty much the moment Jimi Hendrix’s thunderous set closed out the festival, Woodstock was primarily significant as a media construct.

Not only was the TV and newspaper coverage of the event virtually unprecedented, it was surprisingly positive, mainly because the chaos seemingly in the offing once the organizers gave up on restraining the couple of hundred thousand non-ticket-holders trying to get in didn’t materialize. Belatedly declaring the festival free to all comers may have amounted to emergency surgery to prevent a disaster. However, it also turned out to be a genius PR move, raising Woodstock’s countercultural credentials to the near mythic level that Lang and his partners have been cashing in on ever since.

Then came the 1970 documentary, which millions of teens nationwide were able to convince themselves was almost as good as having been there in the flesh. In some ways, it was better, since even the seediest movie theaters have functioning latrines and catching a ride home was seldom a concern. Between them, the movie and its platinum-selling soundtrack album played a downright evangelical role in bringing the counterculture to the suburbs, reaching down to high-school kids and out to heartland precincts where sightings of actual hippies were rarer than memories of Halley’s Comet.

Woodstock-the-media-construct also created a euphoric impression that the rock audience and the 30-odd very different musical acts on the bill all shared the same sensibility and values. “Woodstock Nation” and all that. Aside from a certain propensity to dippiness, however, was that ever remotely true? Along with the somewhat more suspect Jefferson Airplane and sui generis Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead were the only band on hand representing the genuine Haight-Ashbury ethos, as they would continue to do for decades after it was a dead letter to everyone but Deadheads. They were also so unhappy with their own performance that they refused to allow its inclusion on the soundtrack album, and so much for solidarity right there.

By and large, youth-culture writers who began bemoaning the audience’s “fragmentation” a few years later were mourning the demise of an illusion that Woodstock had successfully fostered if not flat-out invented. Except on acid, which undoubtedly helped, it’s hard to imagine fans of, say, folkie gamine Melanie, greaser 1950s revivalists Sha Na Na, or even Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young having much of a Venn diagram overlap in real life with Hendrix freaks, Who enthusiasts or even everyone exhilarated by Sly and the Family Stone — the only major African American act represented, incidentally or not-so-incidentally. And where Ravi Shankar fit in is anybody’s guess.

Not even all of the headliners bought into the myth, then or later. Pete Townshend was so disgusted by his Woodstock experience that he’s said the festival inspired the Who’s balefully minded “Won’t Get Fooled Again.” But the tune that crystallized the opposite view was Joni Mitchell’s fatuous “Woodstock,” which captured the essence of chimerical generational bonding at its most self-congratulatory. Appropriately enough, Mitchell wrote it while watching TV coverage of the festival, which she neither performed at nor attended.

Con artists in guru disguises

Even as the counterculture began slouching toward narcissism, the dregs of the original hippie impulse had sprung out of Spahn Ranch in horrifically grotesque form. Con artists in guru disguise had been preying on zonked-out runaways and escapees from privilege from almost the earliest days of the Haight-Ashbury scene, but only Charles Manson fantasized about luring them into butchery to instigate a race war.

The prevailing cliché used to be that Woodstock’s dream-killing doppelgänger was the disastrous Rolling Stones free concert at Altamont Speedway that December. (Death toll: four, including one stabbing just yards from the stage.) But the verdict everyone is citing lately is Joan Didion’s, from her 1979 collection “The White Album”: “Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community, and in a sense this is true. The tension broke that day. The paranoia was fulfilled.”

Is there even one think piece about “Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood” that hasn’t featured that quote, the one you’re reading included? Because Didion’s vantage point was more specialized than she let on, her generalizations often have their dubious side. “What Didion never got,” her fellow novelist — and unlike her, native Angeleno — Steve Erickson recently grumped, “is that Hollywood is not the same as L.A.”

Nonetheless, at an it-could-only-happen-here level, the Manson murders do feel specific to Los Angeles writ large in a way the Altamont debacle never did to San Francisco or the Bay Area. That’s why they’re the key event — or rather (spoiler alert!), non-event — in Tarantino’s bravura, unexpectedly lyrical, emotionally complex love song to the ’60s he was just barely alive for, but whose pop-culture referents he’s thrived on ever since.

From the start, the movie is a gorgeous conflation of the actual 1960s with “the ’60s” as yet another media construct, which is the version dearest to Tarantino’s heart. The elaborate reconstructions of Hollywood Boulevard and other L.A. landmarks the way they looked in 1969 are the gateway to entering his fantasy, not yesteryear’s reality.

One of the funnier complaints from counterculture die-hards about “Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood” is that the movie is “anti-hippie.” True enough, anyone seeing Woodstock Nation’s seedy side for the first time through Tarantino’s eyes would probably conclude these weirdos were bad news. Of course, though, we aren’t really talking about Woodstock Nation; we’re talking about the freaking Manson family. Can anyone really object to seeing them get their gory comeuppance in Tarantino’s alternate universe? If Leonardo DiCaprio’s past-his-prime TV star and Brad Pitt’s veteran stuntman do tend to get the two confused, that’s because they’re disgruntled at hippiedom’s reminder that their own sell-by date is near.

Crucially, on the other hand, the movie’s Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) thinks hippies are just wonderful. What makes that important is that she’s the movie’s patron saint. The scene of her happily gabbing away in her car with a bedraggled but game hippie hitchhiker she’s picked up before the two women share an affectionate goodbye hug redresses the balance considerably. Tate’s fairy-tale survival at the end is an affecting reconciliation of not only Old and New Hollywood — chic stand-ins here for butch, Marlboro-mannish Middle America and ethereal Woodstock Nation, more or less — but of the historical 1960s and the decade’s “We are stardust, we are golden” might-have-beens.

Such reconciliations, needless to say, only happen in movies. The utopian impulses of the 1960s were a fairy tale too, and the only thing that gave this one a temporal validity was that millions of people believed it or, at the very least, so earnestly wanted to. Even Charles Manson couldn’t totally kill the beauty of that illusion. As for Tarantino, he’s never been a filmmaker with any use for peace, love and understanding. But on the evidence of “Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood,” he does believe in magic. Maybe that’s enough to prove he’s a child of the 1960s after all.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.