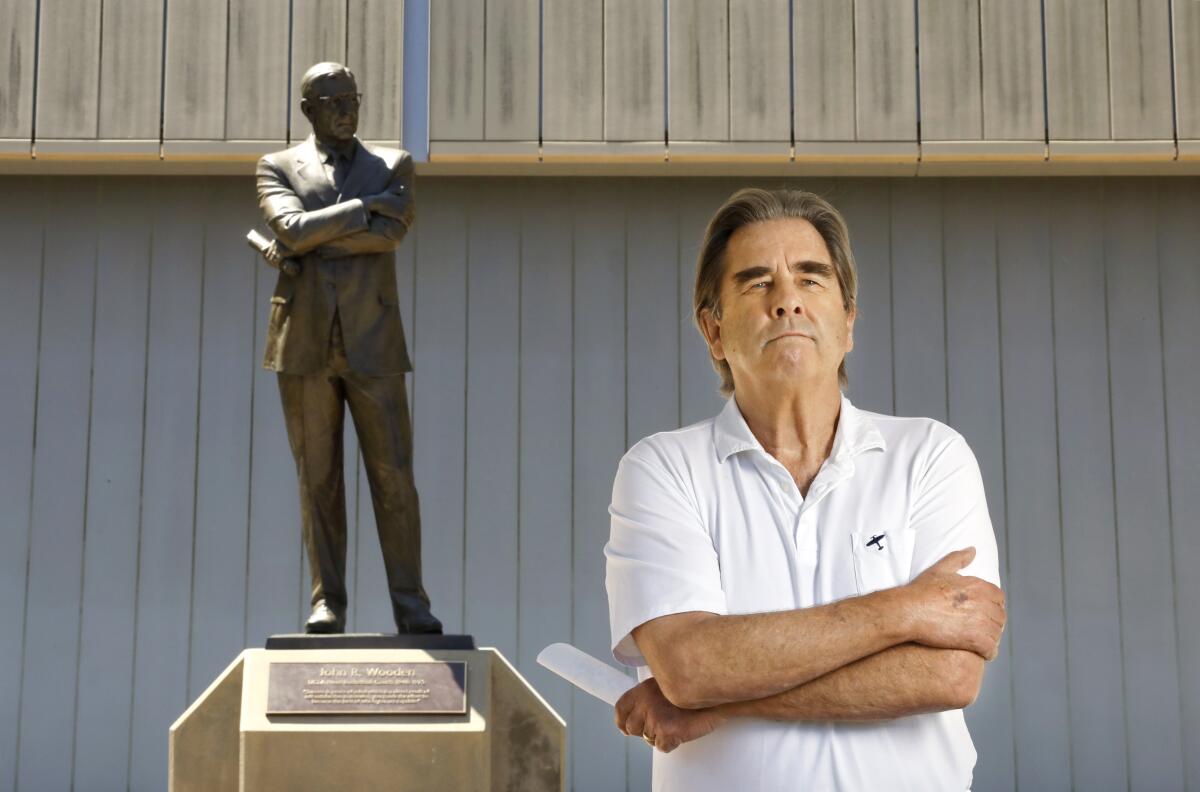

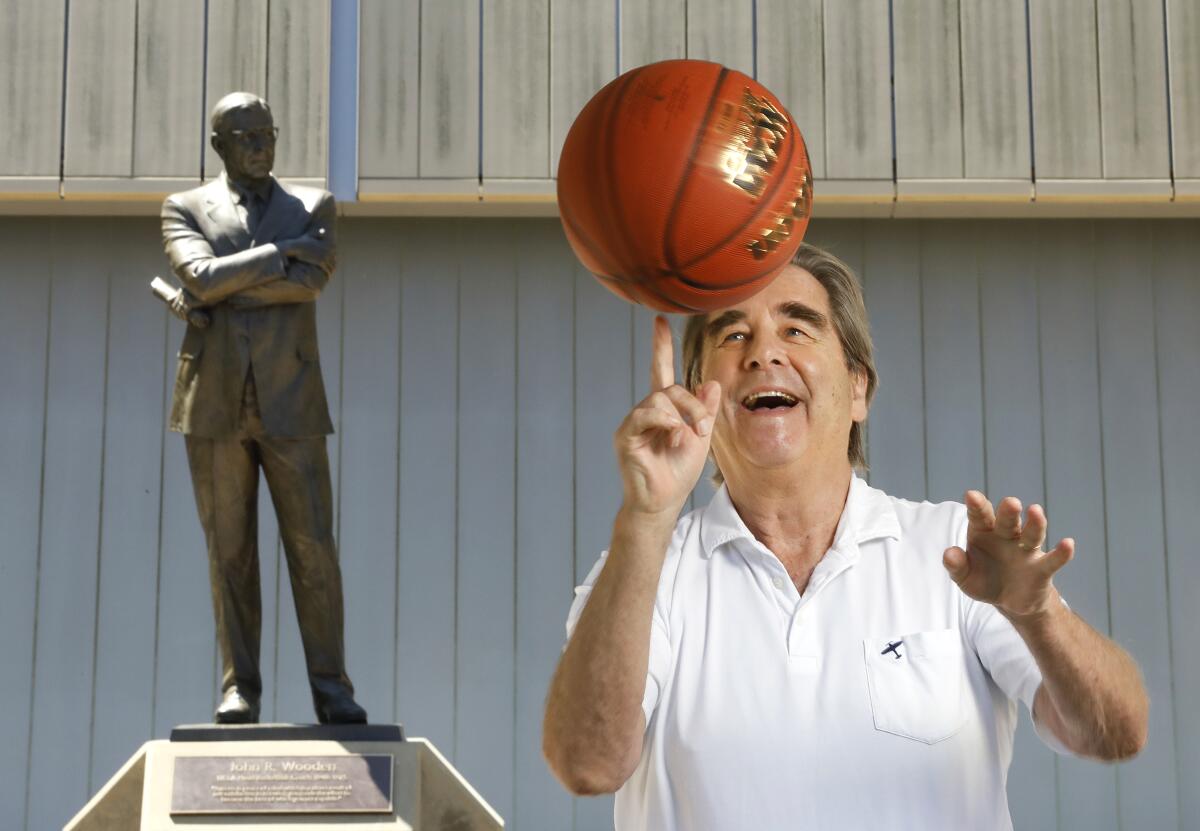

Q&A: Beau Bridges channels his former basketball coach, UCLA legend John Wooden

- Share via

Before Beau Bridges played roles in “The Fabulous Baker Boys,” “The Second Civil War,” “Homeland” and other movies and TV shows, he played basketball at UCLA. And though he played for only one season, he stayed in contact with his coach: John Wooden, who guided the Bruins to an unprecedented 10 national championships in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Bridges will portray the late American sports icon in a new one-person play, “Coach: An Evening With John Wooden.” The piece brings audiences into Wooden’s modest Encino “den” for a session of his signature retirement pastime: storytelling. The time he bailed Bill Walton out of jail for protesting the Vietnam War on Wilshire Boulevard. The lessons he learned from Kareem Abdul-Jabbar about racism in America. The moment he first laid eyes on the love of his life, Nell, his wife of 53 years.

John Wilder — the seasoned writer-producer of the late-1970s NBC miniseries “Centennial,” among others — makes his playwriting debut with the piece, which will be performed Wednesday and Saturday at the Hurst Theatre in Colorado as part of Theatre Aspen’s festival Solo Flights.

Ahead of the play’s world-premiere reading, Bridges, 77, spoke with The Times at UCLA about trying out for Wooden’s team, observing Coach’s lessons on set and preparing to portray his mentor onstage, alone.

You’ve played real-life figures before, including James Brady and Richard Nixon. How are you feeling about portraying Wooden?

I definitely feel a responsibility to get Coach right. I was around him enough to have a good memory of what he was like. He was such an impressive individual that he would stand out during any generation, but particularly in this one, because there’s not many men left like him. So decent, right to the bone. I don’t know if he was devoid of ego, but his quest wasn’t for fame and fortune. He just wanted to make a difference in people’s lives.

He was a real mentor to me, but he also had a very dry sense of humor. When ESPN interviewed him for their awards ceremony, the interviewer asked him, “Is it true that Beau Bridges played for you?” And Coach said, “Yes. He wasn’t very good.” I couldn’t believe it! The next time I saw him I said, “Coach, what the hell? Why did you say that about me?” And he said, “Well, you want me to tell the truth, don’t you?” His face was very stoic, but he was funny as hell. I liked that about him. I’ve got to practice that.

You were a walk-on for UCLA’s freshman team. Were you intimidated by tryouts?

Yeah. I was a pretty decent high school player, and when I graduated I enlisted in the Coast Guard Reserve and played on the Coast Guard team. That was a lot of fun because we played the Navy and the Marines, and there were some pretty good players, so my game kind of upped a little bit.

After I finished active duty, I wanted to play on a college team. My dad had played basketball at UCLA, so I was excited to try out. My friends all told me, “You’re probably not going to make the team. The big guys in college are good and they can really move.” And I’m only 5-10. But I was so happy because when I went out for the first tryout, I noticed that the guys playing my position, guard, were not the big guys that my high school buddies warned me about. The tallest guy was like 6-1! But then that guy went for his first layup tryouts and stuffed it behind his back — it was Walt Hazzard, who would go on to become [Mahdi] Abdul-Rahman. I thought, “Oh my goodness, this is a whole other game here.”

I think probably the only reason I made the team was because there was another guy on the team whose leg was in a cast — Gail Goodrich, who became an all-pro. But nevertheless, I did make it. I was totally surprised and I loved every minute of it. I hustled my butt off, went for every loose ball. I think I averaged 1.5 points a game. But it was OK because I got to play with Coach.

Were you open when you first heard Wooden’s signature “shoelace” speech?

No way! When he walked in, he said, “Gentlemen, we will begin by learning how to tie our shoes.” No one laughed, but we were all looking at each other, like, “This guy is nuts.”

He always insisted on two socks, and he said, “You pull each sock up all the way, because you’ll get a wrinkle in there when it’s game time and it could take you out of the game. You lace up as far down as you can, firmly up all the way, not too tight. And always finish off with a double knot, because you don’t want that shoelace to come undone in the last minute of the game. The whole foundation of your game is your feet, so you want to start there.” And he was right.

I remember when my son, Jordan, went to one of Coach’s basketball camps here in L.A. It was an overnight camp, he was all excited. Coach comes in. “Gentlemen, we will begin by learning to tie our shoes.” Which was so great. He was consistent. He knew a good thing.

What other coaching moments stand out from your time on the team?

I saw him toss out a player. Sometimes we’d stay after and watch the varsity practice, and this guy, who was the highest scorer on the team, threw a ball really hard and hit this kid, who was just like a walk-on. Hit him in the chest during a scrimmage. Coach leaned into the guy and just spoke loudly enough so that we’d all hear him, not yelling at the guy or anything. He said, “Pack your bag, clean out your locker. You’re through here at UCLA.”

This guy was averaging over 20 points a game for the varsity, and he was done. Team was first for him all the time. He always said, “I’d much rather have a team that plays together well than three guys that are all-stars on a team.”

After that season, you transferred to the University of Hawaii, and then you left college to pursue acting. But you two stayed in touch?

Yeah. Coach kept in touch with a lot of his players. We would see each other maybe once every couple of years. He would always have breakfast at a place called VIP’s in the Valley, and players would go there to hang out with him and introduce him to their kids. I did that with my family, and they all got to know him. He was so gracious with everybody.

I think I became aware pretty early on of how important he was going to be for me. It wasn’t like I was a bosom buddy of his, we didn’t hang out constantly, but it was more about who he was and what he represented that impressed me. His whole thing in Pyramid of Success is that success had more to do with finding peace of mind, which is leaving the task knowing that you’ve done your very best, and then you can’t lose. It’s just such a simple thing, and it’s so true. It’s really guided not only my career but my life. I’ve handed the Pyramid of Success to all my children, I coached all my kids’ teams and I handed it to all the kids I coached. I hand it to young actors now that I work with. Because it’s beautiful.

How has the Pyramid of Success come into play throughout your acting career?

Making movies is such a collaborative effort. I mean, it has to be. And when it’s not, and when you’re working on a set that’s not a collaborative effort, which is usually determined by the director, it’s tough.

Probably our biggest challenge making films or doing a play or a show is ... time, because we usually don’t have enough time to do what we think is our best, so everyone is really pushing to get the most out of each other. And when you have a big, strong ego in there, that slows the process tremendously. Because when the problem comes up, instead of a bunch of people jumping on and saying, “OK, how can we figure this out?” the ego guy in there is going to be blaming somebody. “He did this, I had nothing to do with that.” Doesn’t matter, does it? I mean, what matters is, when you’re all done, that you all know that you’ve done your best. What else can you ask from a person? Nothing.

I’ve tried to live by many of his precepts. “Make each day your masterpiece.” “Be quick but don’t hurry.” They weren’t things that he had thought up or imagined, they were from his father. Those things were coming from a different era when people were conscious of respect, and how to teach your fellow human beings. We’ve kind of gotten away from that, I think. That’s the reason why I want to do this play, to reintroduce Coach to people that didn’t know about him. Who knows what my schedule is going to be like later on, but this is a project that I’m really keenly interested in and would love to see where it goes.

Wooden was also well-known for his love for his wife, Nell.

That was a wonderful relationship and a wonderful marriage. He loved her very much, you could tell. She was always there at every game. He had trouble with his temper, and his wife helped him with that, actually, and challenged him about it.

As we all know, UCLA wanted to name the new basketball court after him, and he said no. He said, “I didn’t win those 10 national championships. My wife was there with me the whole time.” Then, her name had to be first, because that’s how important she was to him. So of course, she’s a big part of the play; it’s essentially a love story.

How would Wooden fare today? These days, coaches are like celebrities.

It certainly is different now than it was when Coach was doing his thing, but I think he had such high-profile players that he probably got into some of that with Kareem and Bill Walton and all those guys. But he’d never take anything for himself. In fact, he was very frugal. His office never changed, his condo in the Valley never changed. His den was just exactly the way it was. If we get a chance to do this play, then we’ll re-create that den.

Why do you think he never coached in the NBA?

I don’t think he ever really wanted to. He was more interested in grooming young men to gentlemen, and he wouldn’t have had gotten to groom players and teams that way. Coach saw coaching as teaching; he considered himself a teacher, which he was before he was a coach. I think that made him stand out as well.

Coincidentally, your upcoming roles see you not only as a basketball coach (Comedy Central’s new series “Robbie”) but also as a teacher, in the movie “Acting: The First Six Lessons.”

[Laughs] That’s right! My daughter Emily and I wrote the play about 10 years ago, and it was based on a book written by Richard Boleslawski back in 1938. He was a student of Konstantin Stanislavski, who created the method of acting.

It’s a two-hander, a teacher and his student, whom he calls the Creature. We just shot the movie in Sarasota, and now we’re editing. Emily plays the student, and she directed me in it. I had wondered what that would be like, but she was fantastic. I told her, I said, “Be nice to this old man!” And she was.

Fall theater season highlights for Los Angeles include a musical version of “Almost Famous,” Bill Irwin in “On Beckett,” a revival of August Wilson’s “Jitney” and a new stand-up show by comic Mike Birbiglia.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.