Meet six artists making the public art you’ll soon see on Metro’s Crenshaw/LAX Line

- Share via

A mosaic, 92 feet long, reveals slices of a Los Angeles sky. Dynamic layers of color and texture capture the soundtrack of Hyde Park. Hundreds of stained-glass pieces, arranged to look like bursts of energy, emit colorful reflections on the ground.

When the Metro Crenshaw/LAX Line opens next year, the project’s eight stations, spanning 8.5 miles, will come to life with dozens of public art pieces. In 2015, 14 of more than 1,200 applicants were selected to create art for the transit line that will zip through Los Angeles, El Segundo, Inglewood and parts of unincorporated L.A. County. The works, many made with tile, enamel and glass, are intended to capture the spirit of the historically rich neighborhoods the trains will sweep through.

“When we look at artwork for new projects, we’re really looking at diverse representation in every sense of the word, including diversity of approach,” says Zipporah Yamamoto, arts and design director for Metro. “And so the artwork is as varied as you would imagine from a city that is as diverse and a cultural hotbed like Los Angeles. We think there’s something for everybody.”

Even so, controversy and criticism has surrounded the Crenshaw/LAX line since it was announced, particularly for its potential to adversely affect the predominantly African American communities along the project’s path. Concerns over gentrification, rising housing prices and demographic change in the Crenshaw District inspired Destination Crenshaw, a 1.3-mile open-air museum meant to revitalize the core of black L.A. that has also raised questions about displacement.

Partly in anticipation of these concerns, all the artists — whether native Angeleno, transplant or out-of-state inhabitant — were given research about the neighborhood that corresponded to the station for which their art was commissioned, be it Expo/Crenshaw, Martin Luther King Jr., Leimert Park, Hyde Park, Fairview Heights, downtown Inglewood, Westchester/Veterans or Aviation/Century. And each project had to have a community engagement component, which led many of the artists to spend time in the neighborhoods.

“It could be anything from mentoring young students in the area to working in a collaborative way with residents,” Yamamoto says. “It was a little bit different for each artist, and it connected with that artist’s practice and approach to the work.”

The Times spoke to six of the artists.

Mickalene Thomas

When Mickalene Thomas was chosen to create art for the Leimert Park station of Metro’s Crenshaw/LAX line, she looked to iconic elements of the community’s landscape — including the Art Deco-era tower of what is now the Vision Theatre — then collaged them. She wanted residents to recognize the images in the piece.

“I think it’s important to think about the environment — about the people who live within those environments and will see this work every day,” Thomas says about being commissioned to produce a public art piece. She doesn’t necessarily think of it as her art. It’s the community’s.

In addition to the Metro commission, she’s been working on a series of collages and portraits for art shows, including one titled “Femmes Noires,” which just opened in New Orleans. The work, she says, is about celebrating black women, about “reimagining the black model through images, through the media, through our historical context” using photography, paintings, video, film, performance and silk-screen installations.

On a crisp late fall day, hundreds of South L.A. community leaders, activists and longtime residents convened on the top level of a parking structure adjoining the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza shopping center.

It’s all kept her busy. For the last eight to nine months, Thomas has been almost entirely consumed by studio production.

She’s also a mother of three children, ages 7 to 12: two girls and a boy. Every weekday morning after she takes the kids to school, she hops on an electric moped, stuffs her dog into her doggy bag and rides to her studio in Brooklyn.

With the help of her team, she gets to work. She returns home at day’s end, reads or meditates before bed, and wakes up the next day to do it all again.

“Right now,” she says, “there hasn’t been really any time for any other activity than studio production.”

Mickalene Thomas, up close and very personal

Born in Camden, N.J., in 1971 and raised in Newark, Thomas was raised by a single mother who worked as a social worker. “A creative and visual person,” Thomas says, her mother loved fashion — she modeled in the 1970s — and had a deep art appreciation that motivated her to enroll Thomas and her brother in after-school art programs.

After high school, Thomas moved to Portland, Ore., where she dabbled in theater and pre-law as a student. She immersed herself for the first time in artistic communities there. “I started really exploring and experimenting on my own,” she says.

So she dropped out and moved to Brooklyn to pursue art full time at the Pratt Institute. After earning her bachelor’s degree, she attended the Yale School of Art for a masters in fine arts, graduated in 2002 and did a yearlong artist residency in Harlem.

Her cross-country experiences served as fodder for inspiration. Her mother also became a profound influence for her art, which centers on black female empowerment.

The women she aspires to capture in her work, she says, are strong yet vulnerable, have prowess, charisma and fortitude. Women that persevere and are strong-willed. Women like her mother.

“Those are the type of women you want to look toward as mentors and the type who need to be celebrated,” Thomas says.

Meditation helps spark her creativity, as does Jet, the African American magazine she grew up reading. There there is this sage advice her mother imparted: “Be true to yourself and make what you’re going to make and have fun. Once you stop having fun and stop enjoying it, then do something different.”

So long as she’s aware and observant as she walks through life, Thomas says she will always find inspiration. It’s something she hopes to bring to the Metro riders who will soon find her art as they disembark from their train.

“I hope they’re inspired,” Thomas says, “that they see a sense of themselves and their community.” And she hopes it brings them joy. “If anything, black joy.”

Rebeca Méndez

When Rebeca Méndez was 12, her parents gave her a giant wall in their home to paint what she pleased. “The responsibility I felt was enormous, and it was really nerve-racking,” she says.

Inspired by Henri Rousseau and Paul Gauguin, she painted a jungle, with jaguars, giraffes and exotic birds. Later, Henri Bergson’s idea of élan vital — described by the French philosopher as “the explosive internal force that life carries within itself” — fueled her work. As did these words by composer Karlheinz Stockhausen: “We are all transistors, in the literal sense. People always think they are in the world, but they never realize that they are the world.”

Méndez’s father would come to tell her that art was an unrealistic career pursuit, but it was too late. They’d already nurtured her interest.

Born in 1962 and raised in Coyoacán, in southern Mexico City, Méndez spent much of her childhood searching for archaeological sites in the jungles of the Yucatan Peninsula with her family, camping in the wild for up to a month. Her parents, both chemical engineers, cultivated her observations of the world, what she called “that physical, chemical point of view,” thinking often about what things are made of, how they’re organized, and their cycles and rhythms — all concepts found in her work.

When she was 17, she was on Mexico’s gymnastics team, bound for the Olympics, a feat she’d been training for since she was 7. Then the Soviet-Afghan War erupted in 1979, and Mexico boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.

“Like your sister, you’re going to go study in the university in the United States,” her father announced shortly after the team dissolved. Those words changed her life.

At 18, she went north, to San Diego State University, where she took science, art and design classes. Her art professors encouraged her to apply to the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, where she got in but found the curriculum “tight and restrictive.” Still, in 1984 she earned her BFA in graphic design there and landed a gig designing a poster for a Getty fellowship. She was given free rein over the museum’s collections and, in doing so, happened upon the Fluxus collection.

“And I went crazy,” she recalls excitedly. “That’s when I thought, ‘I want to be an artist.’” She returned to ArtCenter for an MFA while working full-time as the school’s design director, helping to produce more than 300 projects annually. By the time she graduated, her career was booming.

She married in 1985 but divorced four years later and was struck with an acute need to “purify myself,” she says. “I didn’t know how to cleanse myself, so I started looking at how my body cleans itself.”

Kidneys, she thought. “So I was painting kidneys like mad,” she says, often painting overnight and for up to 10 hours straight.

Curious and ever-evolving, Mendez’s interests eventually expanded to other mediums: installation, photography, video and 16 mm film.

Now a UCLA professor of design media arts, the silver-haired Méndez has built a successful career as an artist and designer. Her work has been exhibited from Mexico to Germany, Ecuador to Amsterdam, and has received numerous awards and honors.

When Méndez was approached to design a couple of art pieces for the future Crenshaw/LAX Line, she was thinking about the transit system as a great “equalizer” and about time. About the way people use subways and rails when they are “rushing from one place to another” and how “most of the time, you go into your work and you don’t come out sometimes until it’s dark.”

And she was also looking up to the sky. “I felt that I wanted to show the difference in an understanding of time and the rhythms of the earth versus the rhythms of our working life.”

That became the concept for her massive mosaic, titled “At the Same Time,” for the Expo/Crenshaw station. Over a 24-hour period, Méndez photographed L.A.’s sky in 15-minute intervals to capture its various shades of blue.

The result was a mosaic more than 10 feet tall and 92 feet long. Displaying the sky’s circadian hues, it’s a metaphor for the city’s diversity.

Or, as Méndez put it: “No matter who you are, where you live, what is your social strata, you see the same [sky].”

Jaime Scholnick

Tucked in an industrial block in East Los Angeles sits an unremarkable looking building. The brick walls are generic, and the gray metal garage door is just that.

But inside, Jaime Scholnick’s art studio bursts with vibrant colors. Jars and squeeze bottles of paint, along with spattered plastic containers of brushes, rolls of colored tape and works in progress fill the long, wide work surface in the middle.

This is where Scholnick created a 400-foot-long mural for Metro’s Expo/Crenshaw station. The intricately layered porcelain-glaze-on-steel mural began with images photographer Sally Coates took of the neighborhood around the station. Scholnick added color with paint and linework to transform the images.

“The area is so historical, and it’s gone through so many changes,” she says. “I feel that building up on [the photographs] is kind of creating that historical process too.”

For as long as Scholnick can remember, art has consumed her life. “There’s never been anything else that I’ve done.”

Though inspired by artists like Mark Bradford and David Hammons, she also looks to authors, filmmakers and activists like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, essentially “anyone who is willing to persevere even when the stakes are high and people are dismissing their efforts.”

“Things are really exciting right now. I think that there’s a lot of really good work coming out of all types of music, film, everything,” she said. “Maybe it’s that way because things are so [messed] up.”

Born in Brooklyn, Scholnick moved with her family to California when she was 7. Her father, who worked in aerospace, was offered a job on the West Coast, so they settled in Newport Beach, where she was one of the few brunettes in a sea of blonds, often teased for the way she looked. “I learned early on how awful it was to dislike people based on factors beyond their control.”

Scholnick studied ceramics and sculpture at Sacramento State before earning her MFA from Claremont Graduate University. Post-graduation life, she says, laughing, “was a pretty rude awakening.” To sustain herself financially, she taught English in a factory in Torrance, a job she loved and found fascinating.

In the mid 1990s, she moved to Yamagata, Japan, to study papermaking. For the next five years, she studied and made art. “Everything was fodder for ideas,” she says. “A candy wrapper on the ground was, like, so different than anything we had here. I just felt like a sponge.”

Much of the work she created in Japan was inspired by her status as a woman in a male-dominated society. “It’s so hard being a woman there, so that’s what my work ended up being about,” she says. “I’d never had that here, where you weren’t spoken to because you were a woman.”

Scholnick says her work isn’t easily “salable ... it always has a sort of edge to it ... it has a message and so sometimes people find it disturbing.” An art collector once told her she’d ruin her career with her “doom and gloom work.” Her mural for the Expo/Crenshaw station, however, is less edgy.

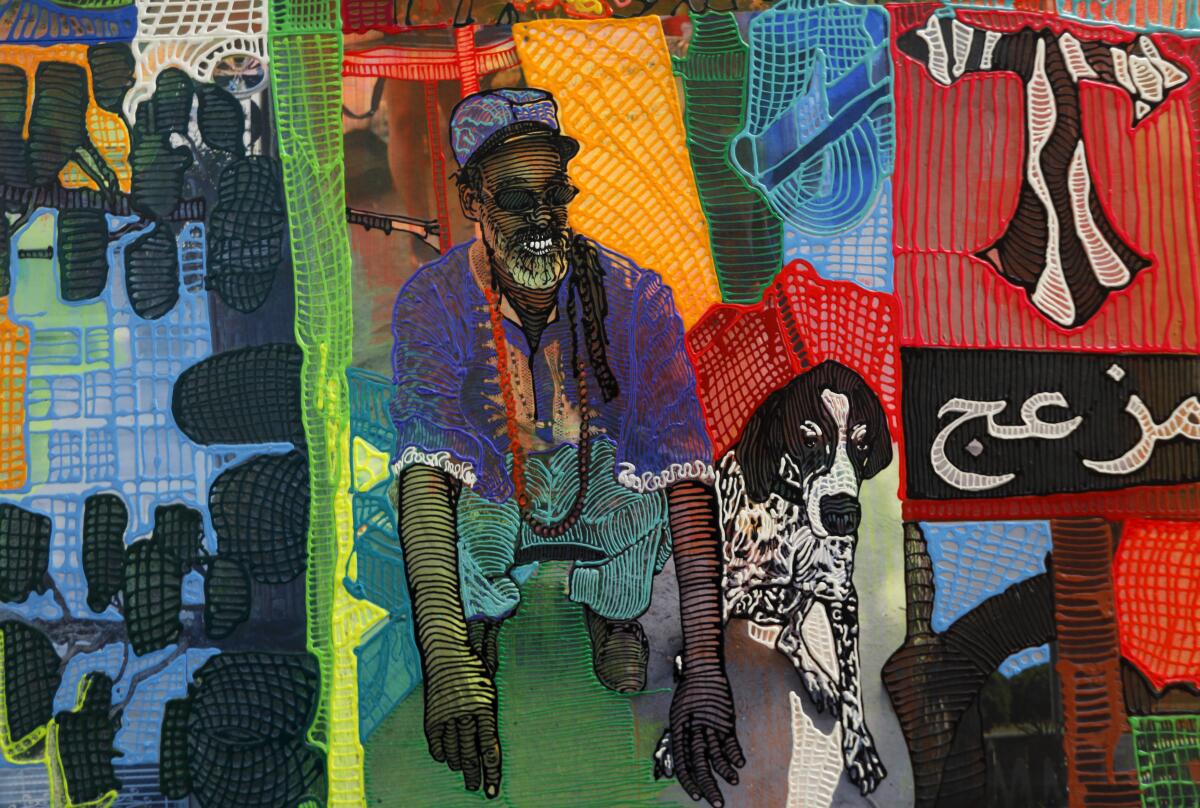

As Scholnick was exploring ideas for the Metro project, she and Coates walked around the community photographing its architecture and talking to locals, asking what they wanted to see on the Metro line. Her late dog Malcolm, a shorthaired pointer suffering from cancer, often accompanied the pair. Named for Malcolm X, he proved to be a handy icebreaker. “He was sort of an entree to meet people.”

Thousands of photos later, Scholnick put the parts together like “a stream of consciousness,” layering the original photographs and collaging different scenes together.

“I was pretty intimidated, to be honest with you,” Scholnick says about being commissioned for this project. “I have never done a public art piece.”

That didn’t stop her. Scholnick isn’t a person who lets fear get in the way.

Eileen Cowin

Not far from the cool of Santa Monica beach is Eileen Cowin’s small studio, where she spends most of her time on photography. Panels of her work reach high against the walls. If there’s an open space, it’s soon filled with photographs.

Besides reading fiction, she doesn’t have time for much else beyond working on photography, video and mixed-media installations. “I don’t really have hobbies. I don’t know if artists have hobbies,” she says “If I’m not with friends or family, I’m just very focused on my work.”

Born in Brooklyn and raised in Queens, Cowin studied drawing and printmaking at the State University of New York at New Paltz and quickly realized her artistic limitations.

“I wasn’t very good at painting,” she admits. “Even my parents didn’t like my paintings.”

But around her junior year, she discovered photography. In a less-than-ideal way.

“I had a boyfriend who was very into photography — he always had his camera — and he told me that I would never be able to learn it because it was too technical for me,” she says.

So naturally, she picked up a camera and started shooting. She fell in love with it. As her work evolved, she began fusing printmaking techniques with photographic images.

Cowin sold her first works in 1969 as a second-year master’s student at Illinois Institute of Technology. With the encouragement of a professor and few expectations, she dropped off her portfolio at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

The museum bought her work.

“That was a really big deal,” she says, pausing, “because I was still in school.” Professors, she says, “really championed the male students,” who were always the first to be recommended for jobs.

But that was less of an issue in the world of photography, a medium then considered a lesser form of art. “You were more discriminated against because you were doing photography,” she says.

That never stopped her from building a burgeoning career as a successful artist and photography professor, first at the now-defunct Franconia College in New Hampshire and later at Cal State Fullerton, where she taught for 33 years before retiring in 2008.

“Now,” she says, “I have my dream-come-true life” — the ability to dive into what she loves and pay more attention to “the extraordinariness of the ordinary” as she creates narratives from her work.

Commuters will soon see that perspective in the art she was commissioned to create for the Crenshaw/LAX Line.

Along each of the Martin Luther King Jr. station platforms, Cowin’s 14 film strips will encourage passengers to design stories for the people in them. The work combines the public with the private, fact with fiction, and gives riders — whose attention often tilts toward their phones — something to engage with.

“I thought, if I can create these little narratives that maybe people could see themselves in ... sort of an ordinariness ... that they might relate in some way to that narrative,” she says.

The scenes and worlds Cowin captured in her project feature residents she photographed along the Crenshaw corridor. In one, she pays homage to civil rights activists, and in a subtle way she references Martin Luther King Jr.

Only those who look closely will notice that one of the photo’s suited-up subjects stands in certain iconic poses of King.

And within the strip, these words: “Depart not from the path which fate has you assigned.”

Carlson Hatton

Carlson Hatton’s parents, both ceramic artists, immersed him in the family trade from a young age. They had the young Hatton help around the art studio, pouring and making molds, and painting cups, vessels and other objects. He learned to draw from his father, from watching TV and from taking any art classes he could.

“And that’s what I wanted to do,” he says. “Having parents who were both artists was a big, big kind of inspiration.”

Now teaching drives his creative impulses.

“The way people kind of enter into a creative field with no set idea of [art] can be really inspirational,” says Hatton, who’s taught art at Santa Monica College for about 10 years.

Hatton, born in San Diego in 1974, moved to New York when he was 18 to pursue art. He’d read about Cooper Union, the then-tuition-free college in Manhattan. “And that sounded like something I could benefit from,” he says. “It was founded by the guy who invented Jell-O, and he also invented the predecessor to the steam engine and the predecessor to the elevator.”

At Cooper Union, he studied all forms of art, but painting was his emphasis. Though he never officially became a printmaker, it was an art form that always resonated with him. “That method of thinking, that method of layering is something that remained very constant in my work.”

As an undergraduate, he participated in a foreign exchange program in Holland before briefly attending art school in Amsterdam.

He finished his four-year program in New York and flew back to Amsterdam for his MFA, where he was provided with “this enormous studio ... I started making big sculptures and big installation projects, and work that was not painting because I felt like I had to take on this ridiculously big studio space I was provided.” When he completed those studies, he couldn’t resist the pull, yet again, of Holland, where he lived until 2001 while undertaking another postgraduate program.

Not long after 9/11, Hatton and his then-girlfriend moved to Los Angeles, a city he’s always loved. But it felt like a mistake. Jobs were scarce. They didn’t know anyone. And it took some time to establish himself as an artist. But they made it work, and he discovered that the numerous jobs he took on — architectural fabrication, window and set design — all used the introductory-level skills he learned in art school. They now factor heavily into his artwork.

“I found that I picked up so many technical skills in that world, and particularly architectural interiors, that I think really factor into my current work,” he says, and helped a lot with bigger projects like this Metro project — these things that kind of go on for a long time and where you’re working with a lot of different individuals and institutions.”

As his largest public art project yet, Hatton thought a lot about its horizontal format. He knew he wanted to create something involving “L.A.’s broad and sweeping horizons” for the Hyde Park station, but he wasn’t sure what its focus would be.

Eventually, he narrowed his interests to the music history of South L.A.’s Hyde Park area and its nature.

“I found it funny that there are historical palm trees in L.A. that have been here longer than most anything,” he says, “and a lot of them are throughout that Crenshaw District.”

Hatton sought the help of several of his art students to take photos in their communities to give him a different perspective of the area.

Having them “show me their neighborhood and their surroundings and their take on a city that we all share together was a really interesting aspect of the project,” he says.

The collective work resulted in a “bright, “vibrant,” “rhythmic” and richly layered project that references, among other things, jazz, the Inglewood-raised saxophonist Kamasi Washington, the late rapper and entrepreneur Nipsey Hussle, and low-rider car culture.

Though it’s been 20 years since Hatton moved to L.A., the city is still revealing itself. When he embarked on the Crenshaw/LAX project, his impressions and understanding of the city shifted.

“It’s been so interesting for me to be able to look at the city in a different way,” he says, “to look at it from a different angle, to open up research about a part of the city.”

In a place that once felt unwelcoming, Los Angeles, for Hatton, has become a place of perpetual discovery.

Kenturah Davis

After settling into a new home in Highland Park, a space she moved into in September, Kenturah Davis is in the midst of a life transition.

She doesn’t cook, so she converted her dining room into her studio space. Her living room is still mostly empty, except for the wooden couch her dad built. She redid its cushions, now cream-colored, and quilted inserts for its pillows using residual fabric from other sewing projects. It’s what she loves about quilting — the part about “being able to use small pieces left over from something else and giving it new life.”

She learned to quilt and sew from her mother, a homemaker. Her father, now retired, was a set painter for TV and film, though he’d occasionally pick up graphic design jobs.

From the time she was young, her parents nurtured and encouraged her artistic expression. She distinctly remembers her father taking her and her sisters to the Rose Bowl to paint en plein air.

Art was as consistent as the air she breathed.

“I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t making it,” Davis says in a cool, calm voice. Her interest in portraits has also been consistent. “That’s been the driving force and being interested in human interaction and the nature of that.”

But as she’s evolved and matured artistically, people’s relationship with language has increasingly fueled her work.

Born in Glendale and raised in Altadena, Davis received her bachelor’s from Occidental College. After she left a job in a gallery, she got the chance to work abroad.

She flew to Ghana in 2013 to take a job as a production manager for her friend’s clothing line. What was supposed to be a six-month trip became a stay of nearly two years, off and on.

She’s never stopped going back. And her creative work has been directly, deeply influenced by her time there.

“Everything was just so vivid,” Davis says about Ghana. “I was hypersensitive to all the sensory experiences: the smells, the sights, the sounds, everything.” West African textiles — with their intricate weaving designs, bright hues and meaningful patterns encoded with information — also began influencing her work.

Where most of her art was — and still is — black and white (she’s interested in the relationship between text and a white page), she’s begun incorporating more color into her work.

In the fall of 2018, shortly after finishing her master’s program at the Yale School of Art, Davis landed a teaching gig at Occidental — a move she didn’t anticipate so soon after graduating.

But the opportunity presented itself when a former printmaking professor phasing into retirement invited her to take over a few of her classes.

“It just seemed insane to turn it down.” She remembers how her favorite educators helped her define the kind of teacher she wanted to be.

“What I liked about them is that they created a situation where the class was a time for thinking through a problem and experimenting without necessarily presuming what the results would be,” she says. And that left room for the teacher to also learn.

When she’s not teaching, Davis usually flies to New Haven, Conn., for her yearlong NXTHVN (Next Haven) fellowship, where she’s learning professional development skills, mentoring local youth, and making art in a “beautiful” studio with windows facing the street.

When Davis was commissioned to make art for downtown Inglewood’s station, she had been thinking a lot about “The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows,” the website and YouTube channel by John Koenig, who invents words for powerful emotions.

“I was really interested in one word … ‘sonder,’” a word, she says, “that poetically describes the experience of noticing a stranger and being curious about what their lives are like and thinking about how your life might intersect with theirs.”

It was the perfect word to fixate on for the project, she thought, since trains and public transportation spaces are where strangers often clash, especially in a city where most people drive.

So she took the word and its definition and stamped it on the background of her drawings, drawings of people she photographed interacting with or observing each other who were somehow associated with Inglewood.

She hopes her work inspires curiosity in commuters. Curiosity about the people she drew, about others on the train. She hopes it makes them think about their relationship to language, about the word “sonder.”

And with her art, she hopes to create more opportunities for moments of serendipity.

Residents of South and Central Los Angeles have had far too little access to rail.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.