Inside the Getty photography vaults: How the museum protects historic prints

- Share via

The photo album has been worn soft by the press of countless fingers, its water-stained cover turned the color of spilled coffee. Labeled “London Boys Home, 1857,” the album contains careful portraits of young men accompanied by neat handwritten script detailing biographies worthy of a Charles Dickens novel.

Fourteen-year-old William Ford is shown stiffly sitting in a suit twice his size. His slicked-back hair and high forehead tower above a small, pinched face with a long nose and sorrowful stare. The reader is told that Ford was admitted to the school on June 2, 1855. His parents are dead; his brother is a railway porter who is now out of work.

The school arranged for William to travel to Canada for employment, but his conduct on board the ship was not commendable and he gambled some of his clothes away during the voyage. The last entry in his biography, dated March 18, 1858, notes that our wee hero is in Toronto selling muffins.

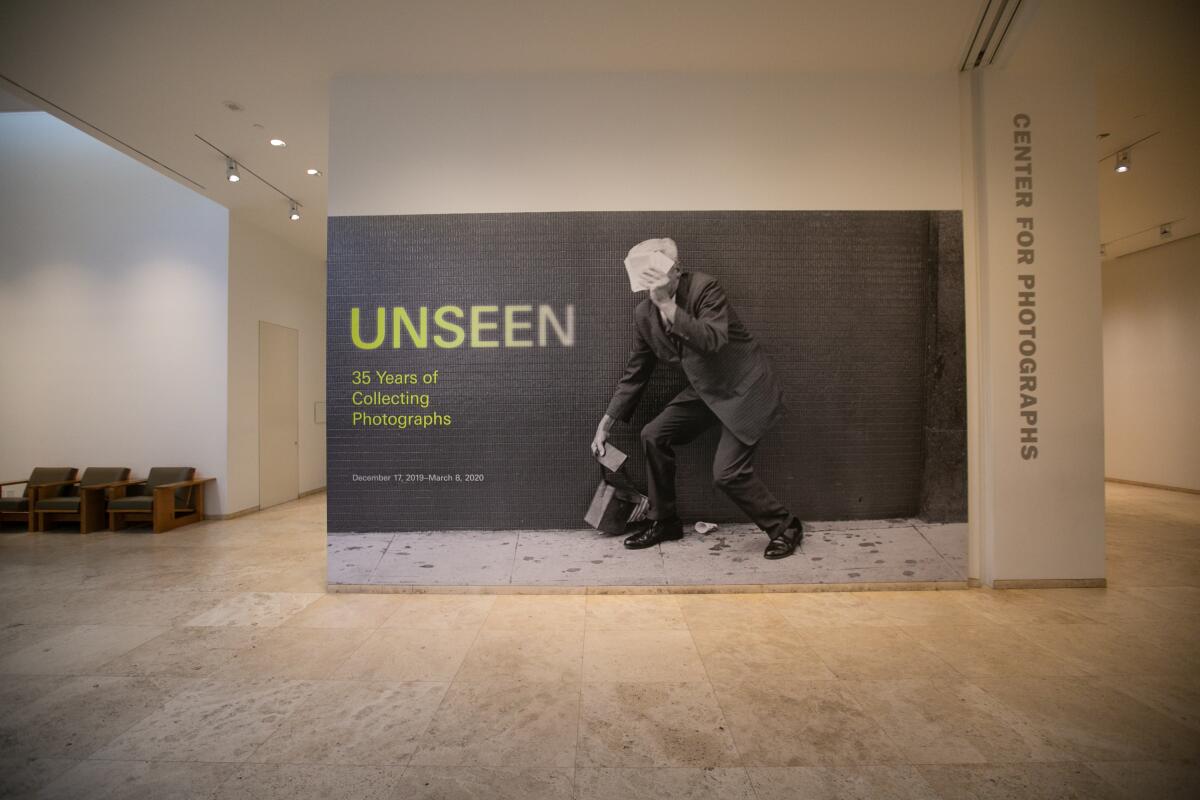

The rare handmade book was rediscovered in the Getty Museum’s main photo storage vault by senior curator of photographs Jim Ganz, who was searching for gems to include in the new exhibit “Unseen: 35 Years of Collecting Photographs,” which runs at the Getty Center through March 8.

Created to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the founding of the museum’s department of photographs, “Unseen” features images from the collection that have never before been exhibited at the museum.

Work by prestigious names like Nan Goldin, Weegee, William Eggleston, Laura Aguilar and Anthony Hernandez share wall space with unknown talent, as is the case with the remarkable salt prints featured in the London boy’s home album or a grisly series of forensic crime photos made by the police in Paris in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Ganz, who collaborated on the project with the other six curators in his department, calls the result a “curatorial mixtape” and notes that objects that have no literal relationship to one another are found next to objects that present the opportunity for making unexpected connections and revelations.

He takes pains to stress that the photos in the show are not the greatest hits of the images not yet seen in the museum, but rather a loving assemblage of images that mean one thing or another to the curators who pieced them together.

“This is a collection of 148,000 objects,” Ganz says during a tour of the storage vault. “So you do the math and realize that most of it hasn’t been shown.”

Like the journey of 19th century portraits of orphans in England to a storage vault in a Los Angeles museum, the much shorter journey of a photo from that vault to museum gallery wall involves intricate interventions that are not be obvious to the casual observer.

Most of the objects in the collection live in one of five vaults, which collectively provide 4,400 shelves and 10,000 square feet of hanging space. Prints are kept safe in archival quality mats and folders inside slender, black solander boxes — rigid containers that protect prints from fluctuations in humidity and temperature, as well as from excessive light. Books and albums are stored in heavy metal cases with glass fronts. Some labels are written by hand, others are typed.

The main vault pairs the look of a library with the chilly, no-frills ambiance of a walk-in cooler. The room is kept at 68 degrees to protect the prints. The vault for color photographs is kept at 40 degrees to slow the inevitable changes with the dyes. Before color materials can be moved in or out, they must spend 24 hours in a transition room with the thermostat set to 55 to prevent condensation from forming on the surface of the work.

“It’s essential that photographs are housed with high quality materials and that the storage environment is climate controlled for long-term preservation,” explains associate conservator of photographs Sarah Freeman, who is part of the team that evaluates each of these factors to ensure they are optimal. Acid-free folders, mats and frame packages are key because they provide protection from handling and the environment. Cool, dry conditions are ideal, and proper air filtration is necessary.

Freeman and her fellow conservators, who work in the lab next-door to the main vault, are also responsible for determining whether or not an object needs treatment. The many options include repairing tears, stabilizing emulsion and the edges of prints, as well as structural work on bindings and book covers. The lab is clean, white and brightly lighted — a quiet place where science is obviously happening.

Conservators also must carefully assess an object’s light sensitivity. Prints made in early days of photography were often created using experimental techniques and unstable chemicals, so exposing them to too much light could cause them to yellow or fade.

“Unseen” features a series of cyanotypes made in the mid-1800s by English botanist and photographer Anna Atkins and her friend Anne Dixon. These showcase a technique that uses iron salts to produce blue-colored prints. The results resemble paintings.

The delicate works of art were determined to be so light sensitive that each Monday — when the museum is closed — a page of the book containing the prints is turned so as not to expose one particular cyanotype to more light than it can handle.

Every object in the Getty’s collection of photography has a back story that is often difficult to suss out. This is where the museum’s collection manager and curatorial assistants get their chance to shine. This group is in the process of cataloging and uploading the entire collection online.

When collection manager Miriam Katz began working at the museum eight years ago, she says that only about 3% of the collection was online.

“Now, as fast as they catalog an image, we’re uploading it,” she says, adding that there are still more than 36,000 objects to go, a process that will likely take another five years.

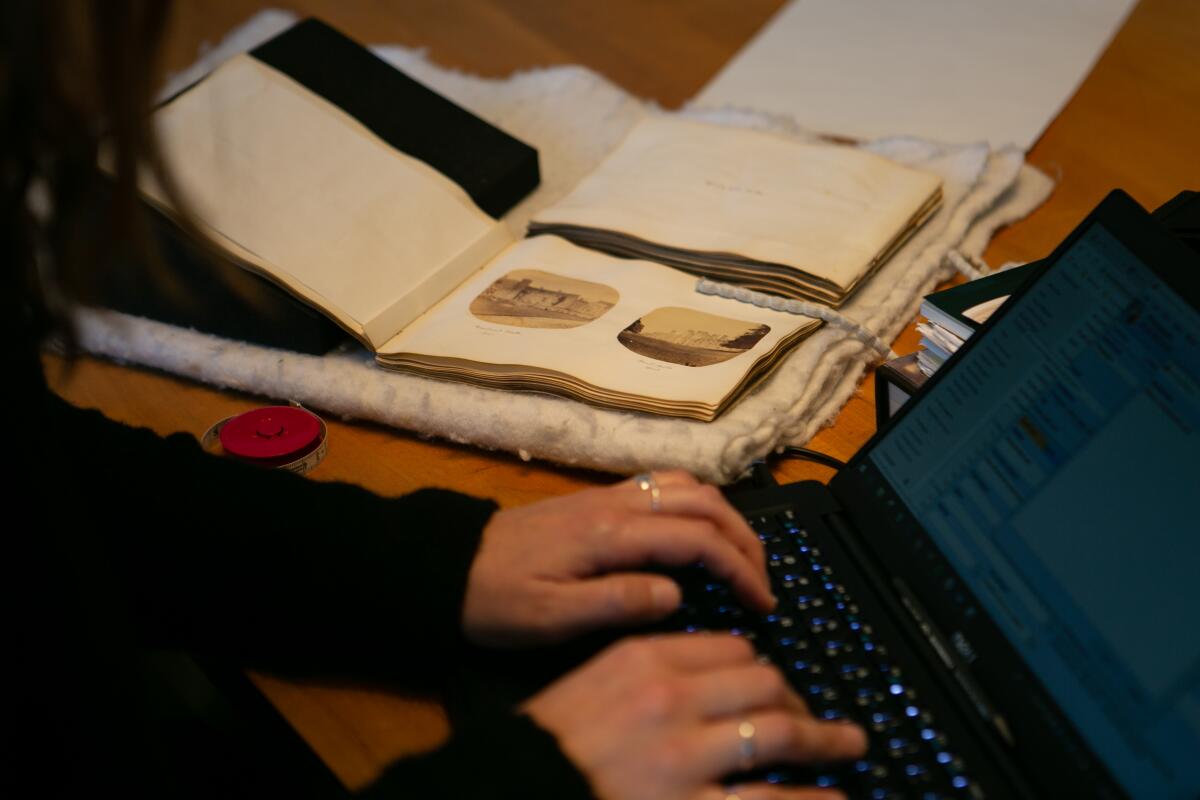

Cataloging an image is a fascinating combination of scholarly research, hard science and imaginative speculation. Before an image is uploaded, the curatorial assistants have recorded as much information as possible about who took it, when, where and why. Historical background that adds meaning to the image is limned, as are identifying characteristics of the print and entries about who owned an image over the years, and where it may have been exhibited.

“To my mind this is the most essential curatorial work there is,” Ganz says, “because if you don’t know what you have, you don’t have anything.”

The curatorial assistants work at long, polished wood tables in the museum’s study room, which is open to the public. A print or album is laid on soft, white cloth. The staffers use a loupe to magnify the image, a tape measure to record its dimensions and a pocket microscope to help identify the process used to create the image.

Then there’s the historical research work, which often can yield thrilling results, as was the case with the mysterious “London Boy’s Home” portraits. When the book fell into the hands of curatorial assistant Megan Catalano, very little was known about it, including the name of the school and where it was located.

She did some digital sleuthing and finally found another handmade copy of the book in the London Metropolitan Archives. This copy identified the school as being in Walton-on-Thames, which is a borough of Surrey about 15 miles outside of London. Catalano now had a place to start, and she began digging through old newspaper records and other historical materials to figure out the name of the school (Hurst Refuge) and the name of the headmaster (James Edmond Harries), who she thinks is likely the person who kept the book.

“It took a very long time, but it was incredibly satisfying,” Catalano says.

The book, which the museum has relabeled “Walton-on-Thames Boys Home Case Book,” arrived at the Getty in 1984 as part of curator and art collector Sam Wagstaff‘s collection. Catalano says Wagstaff acquired it a Sotheby’s auction in 1975.

Catalano hopes that someday someone will try to find the boy’s descendants, and that her research might help with the hunt. Most of the boys were sent to Canada for work, she says, and a few were sent to Australia or Africa.

“One or two entered the Royal Navy, so there may be more information about their fates in other government records or archives in other parts of the world,” she added. “The reports of the boys mostly stop a few years after they arrive in Canada, some having found steady work, others bouncing around. Sadly, one or two didn’t survive the journey or died shortly after arriving in Canada.”

Each image on the wall in “Unseen” has its own story. Visitors need only pull back the curtain on the process of telling it.

'Unseen'

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Tuesdays-Sundays, through March 8

Admission: Free

Info: (310) 440-7300, getty.edu

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.