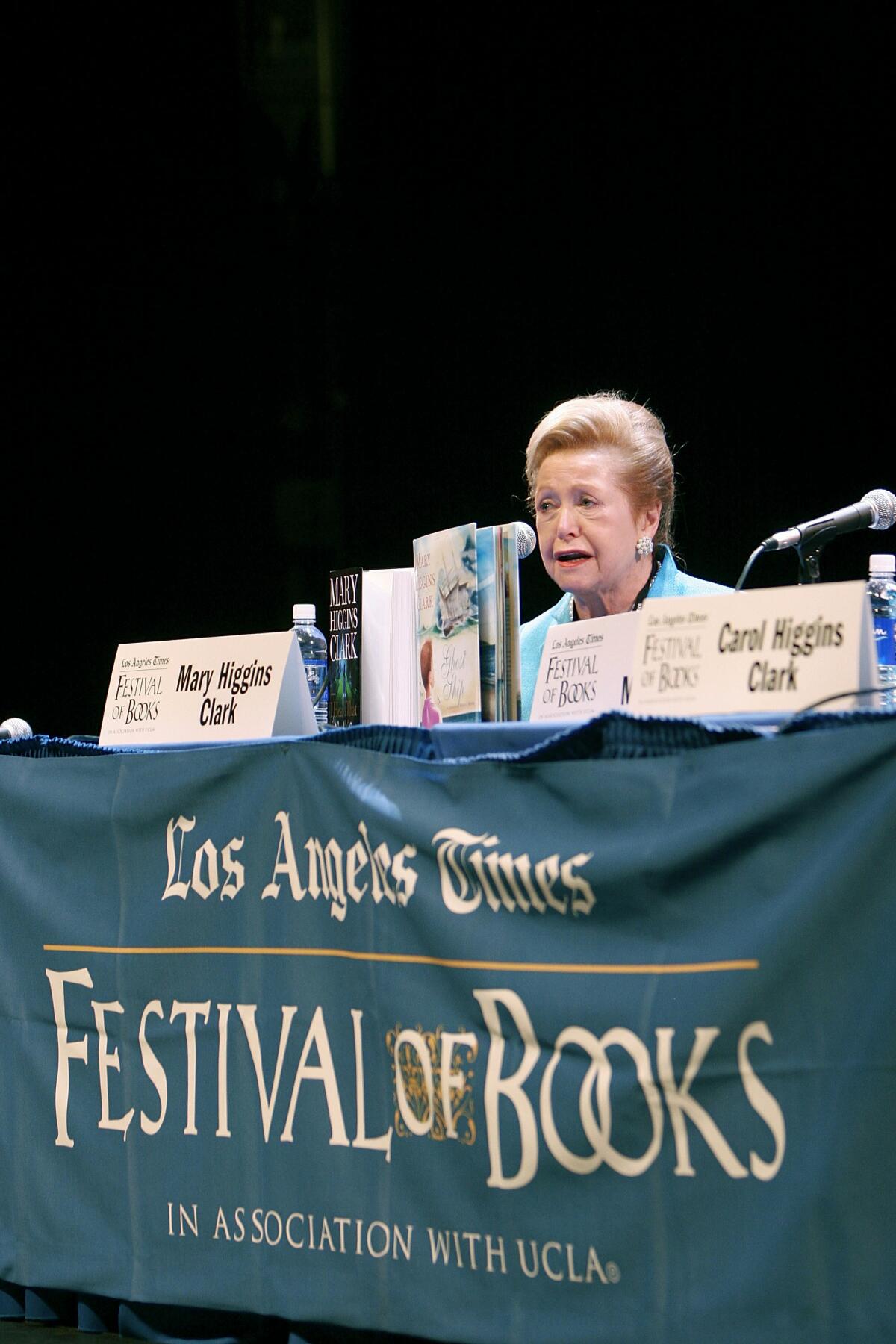

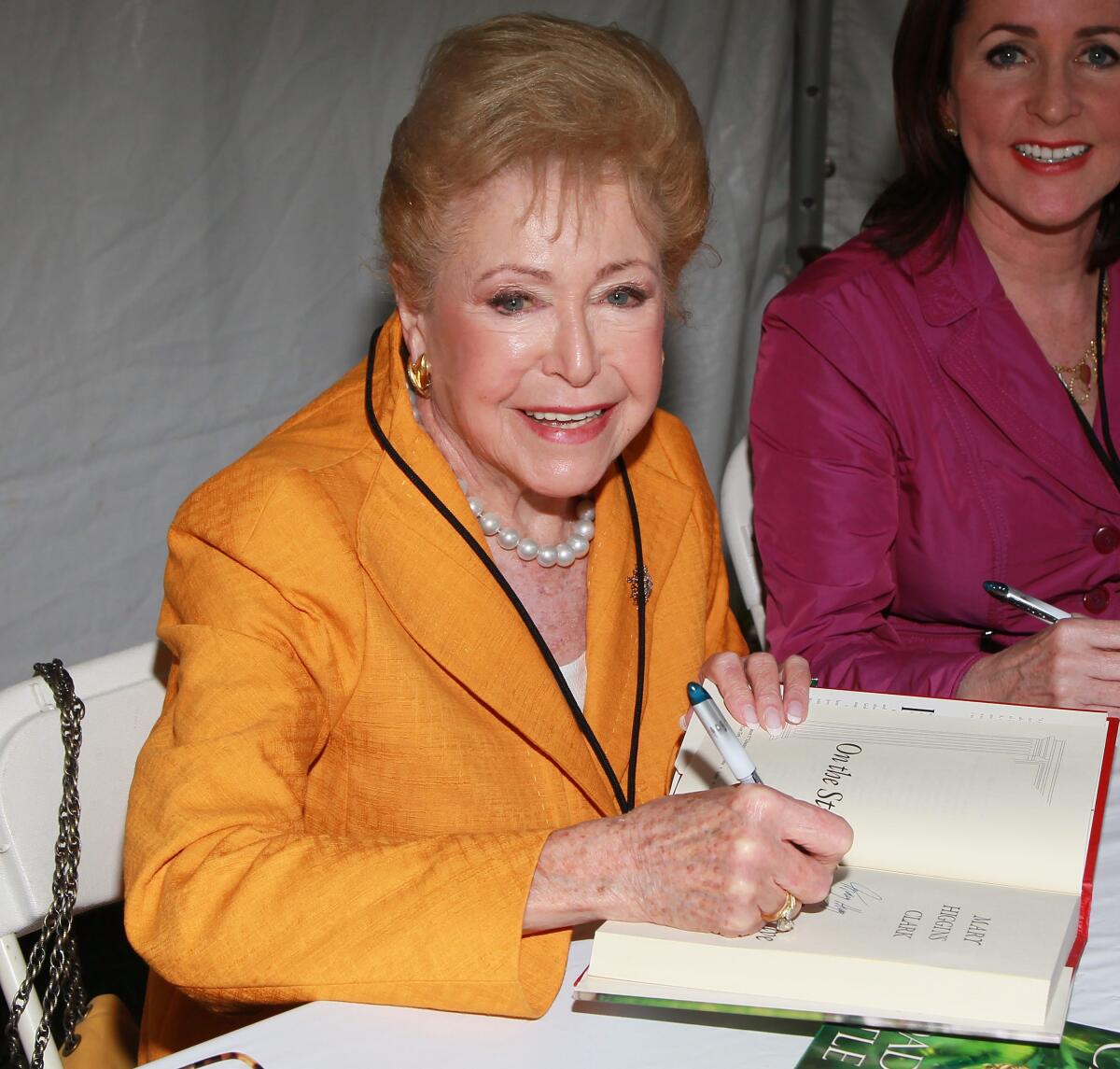

Appreciation: Mary Higgins Clark and her endearing women in peril

- Share via

No one deserved the sobriquet “Queen of Suspense” more than Mary Higgins Clark. She spun anticipatory dread into sly satisfaction. Her style was clean — no profanity or sex — her heroines endearing and her resolutions tactful, with the perfect sting of surprise. Her books embodied the spirit of a tabloid-adoring aunt ready to whisper to you about extraordinary danger lurking just around the corner, waiting to find you.

Clark created a brand, and it resonated. She wrote nearly five dozen novels, largely on her own and sometimes with others. Long before I ever met her, or profiled her, as I did in 2015, I was a fan, devouring Clark novels such as “Weep No More, My Lady” (1984) and “A Stranger Is Watching” (1978) in high school, wondering how she kept me turning the pages so fast.

One of my favorites, “Loves Music, Loves To Dance” (1991), was, I now realize, a gateway into my lifelong fascination with true crime. When I learned of the novel’s inspiration, the crimes of 1950s serial killer Harvey Glatman, I wanted to understand how he could set a snare for potential victims through “Lonely Hearts” ads, and what compelled him to murder these women. Clark’s novel provided many of those answers, updated to the then-present day.

“As soon as I could write, I was writing stories,” Clark, who died Friday at her home in Naples, Fla., once said. She was 92.

Growing up in the Bronx, N.Y., Mary Theresa Eleanor Higgins was reciting her own poems at six and later submitting short stories to the confession magazines in high school. She lived through the Great Depression and the sudden deaths of her father and brother. Writing was at once her refuge and her dream. But to pay the bills she worked as switchboard operator, secretary for an advertising agency and Pan Am flight attendant. The people she met and the voices she eavesdropped on would find their ways into her novels.

In 1964, long before her reign on bestseller lists, Mary Higgins Clark became a working writer while raising five children. Her first husband, Warren Clark, whom she married in 1949, died after a series of heart attacks. Hours before his death, Mary Clark had been offered a job as a radio scriptwriter but demurred so as not to interfere with her aim to sell short stories, as she had done in years past to the Saturday Evening Post, Extension Magazine and other outlets.

But after her husband died, Mary, now a single mother, accepted the job, where she stayed for several years before co-founding her own syndication script company, Aerial Communications. Clark also made the time, writing in the early mornings, to research and publish her first novel, “Aspire To the Heavens,” in 1969. She later characterized the book, on the lives of George and Martha Washington, as a “triumph” although not a commercial success. Poor marketing and a title she loathed doomed the book’s prospects. (It would later be reissued, with greater success, as “Mount Vernon: A Love Story.”)

As her children grew, with two accepted to law school, Clark felt a sense of urgency to earn money. She thought about the books she most enjoyed, the ones she would take to bed after a long day’s work. They were mystery novels, by the likes of Agatha Christie, Charlotte Armstrong and Rex Stout.

Clark became intrigued by the case of Alice Crimmins, a Queens housewife accused, tried, and twice convicted of murdering her children in the mid-1960s. The case — both convictions were overturned — was relentlessly covered by the tabloids. Clark recalled lessons she learned earlier at her NYU writing classes. How phrases including “suppose” and “what if” could transform an idea into a novel.

The result was “Where Are The Children?” (1975). Its hardcover sale to Simon & Schuster netted Clark a $3,000 advance. The paperback publication, and its mainstay on bestseller lists, changed Clark’s life. Every subsequent suspense novel, more than 50 in all, kept her bestselling perch. Readers responded to stories that hearkened to the best mystery writing of the past but whose style spoke to the present. Many also respected Clark’s vow to keep things strictly PG-13, allowing her to enjoy the most catholic of readership, not just in America but around the world (she was especially popular and beloved in France.)

Clark’s suspense novels fused classic women-in-peril narratives by the likes of Mary Roberts Rinehart and Daphne DuMaurier — “Rebecca” was an oft-cited favorite, and one Clark drew from for one of her best and scariest books, “A Cry In The Night” (1981) — with contemporary crime stories published in New York city tabloids, which Clark read faithfully each morning in search of story prompts. She was the inflection point between the domestic suspense of an earlier era and recent psychological thriller blockbusters by Gillian Flynn, Paula Hawkins and Megan Abbott.

Clark, by her own admission, was less concerned with beautiful sentences and social commentary. Her strengths were story, sympathetic heroines and structure. How else could so many millions of readers keep turning the pages of her books, year after year, generation after generation? They could identify with the protagonists, “nice people whose lives are invaded,” and feel catharsis when bad people were caught for their horrific crimes and good people prevailed. As her longtime editor, Michael Korda, once said: “Mary’s great genius is that she writes for but also thinks like her readers, and predicts what her readers will accept and what they won’t. Mary is very certain about what they want and what she wants.”

She could, and did, extend that knowledge of readers’ wants to others. One of Clark’s gifts was her unerring generosity towards writers, in her own family and well outside of it. She co-wrote five novels with her daughter, Carol, and several more (and more recently) with the crime novelist Alafair Burke. Clark was also a longtime member, later Grand Master, of the Mystery Writers of America (who give out an annual award in her name) and co-founder of the Adams Round Table, a monthly writing group that, at stages, included Lawrence Block, Harlan Coben, Nelson DeMille, and Dorothy Salisbury Davis.

If there is an underlying reason why Clark became the “Queen of Suspense,” it might be found in a 1989 interview with McClatchy News Service. “I think the person who becomes a professional is the one who has a need to write. You know, a lot of people have a talent for writing and they say, ‘When I get around to it, I will,’ and if they ever did get around to it they probably could, but they don’t because they don’t have a need. I have a need to write; it’s in my very bones. I enjoy the process.”

That need to write, combined with an unerring, and superbly honed, instinct for what people needed to read, made Clark a grand success for more than four decades. As Clark’s publisher, Jonathan Karp, told the Guardian in 2015, “She’s writing the Great American Standards of suspense novels. She’s singing in a major key and playing big meaty chords and people are applauding at the end of the song.”

Weinman is the author of “The Real Lolita.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.