- Share via

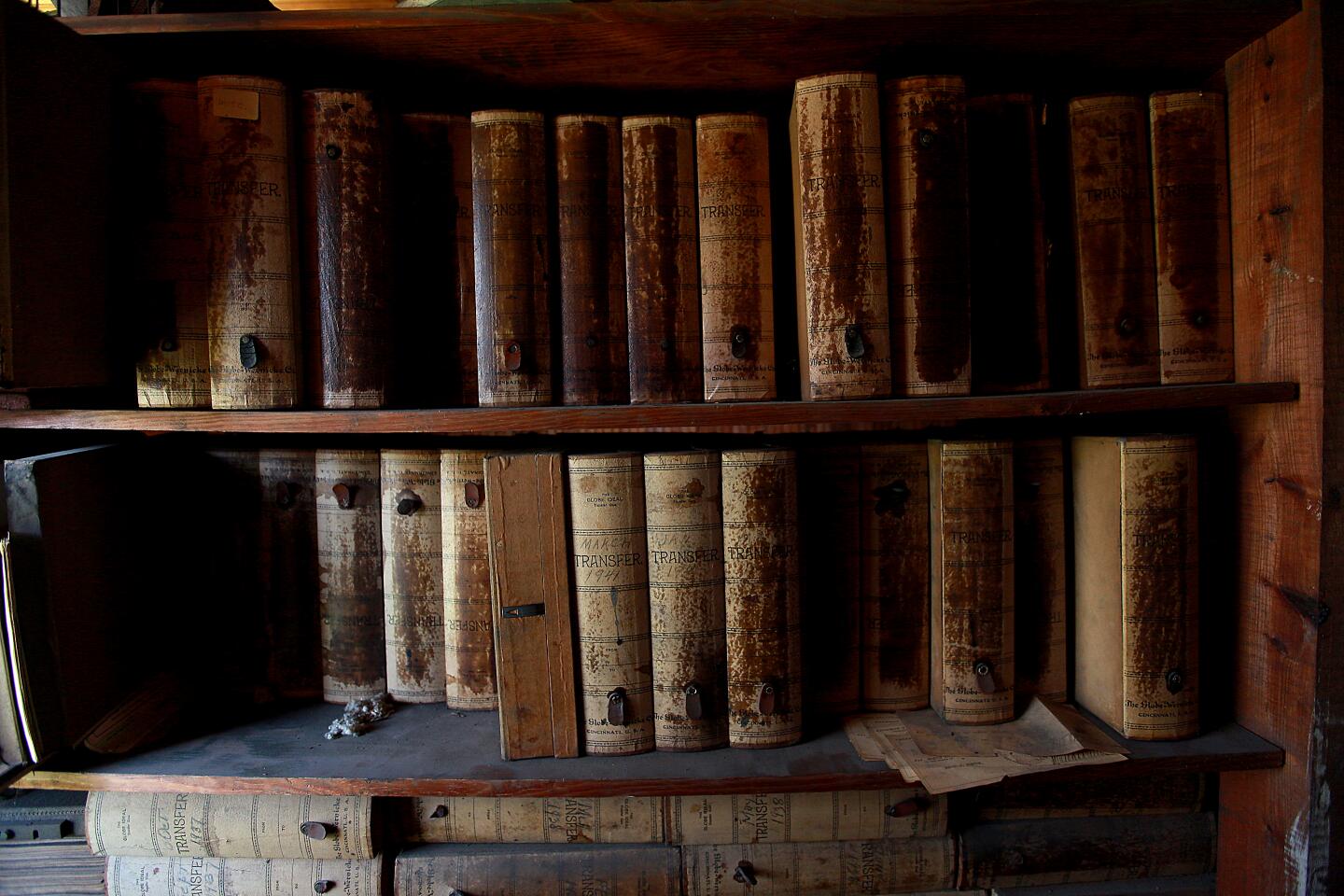

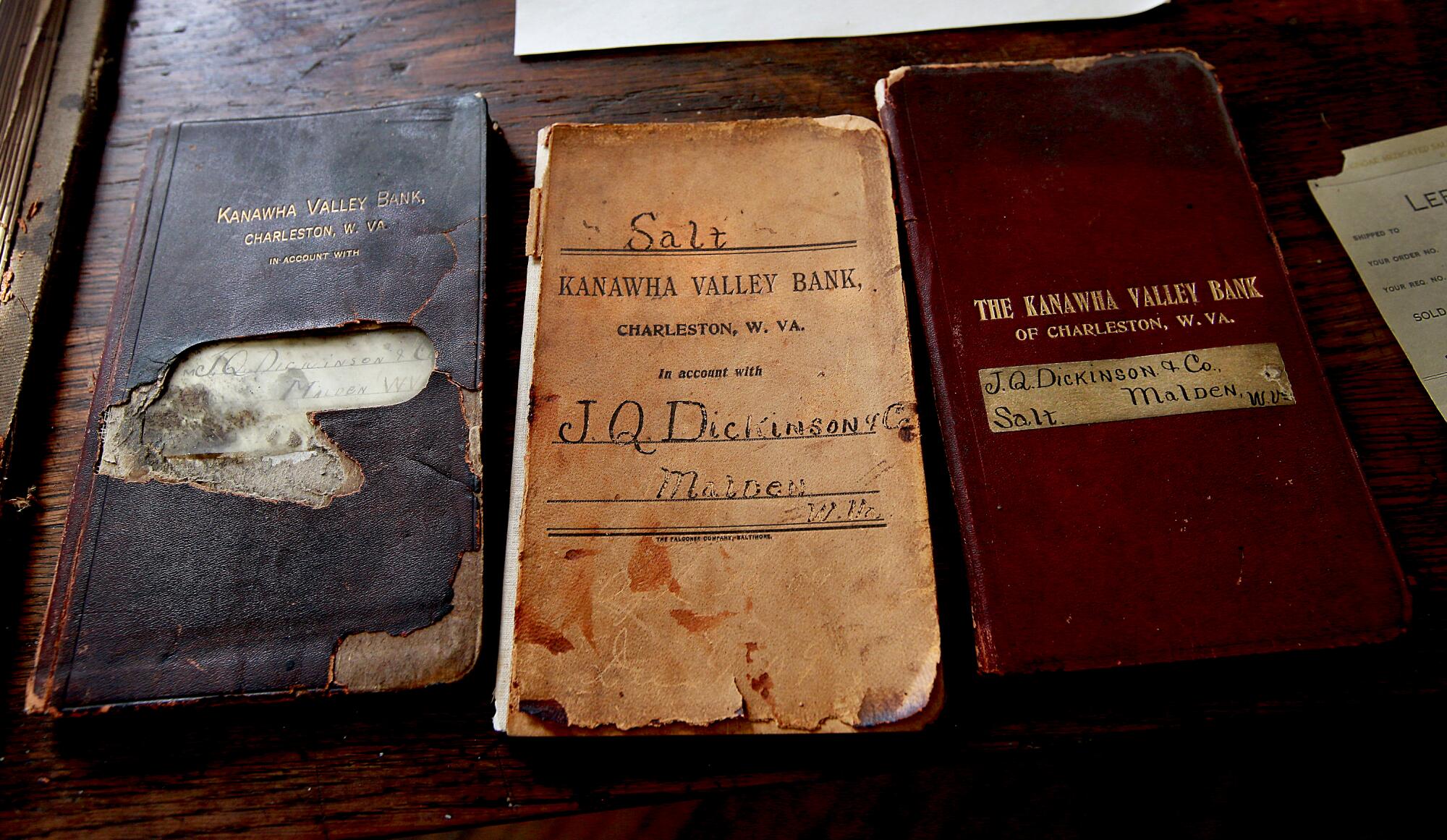

MALDEN, W.Va — Inside the cramped and dusty attic overlooking the pale green Kanawha River in the Appalachian Mountains, stacks of 100-year-old business records — deposit books, letters from customers, employee records — balanced precariously on cabinets, lined shelves and sat scattered across the wooden floor.

Siblings Nancy Bruns and Lewis Payne stumbled upon the trove of documents in 2013 after reviving the family salt business on the same farm where their ancestor William Dickinson lived and worked in the 1800s. The duo are seventh-generation descendants of Dickinson, the shrewd businessman who helped develop the region’s booming salt industry.

The documents and other items, such as photographs and vials of salt, stashed away in the attic and spread throughout the old office building, paint a picture of familial tenacity. For more than 200 years, the business evolved for survival, stretching across salt, chemical industries, land holding and banking.

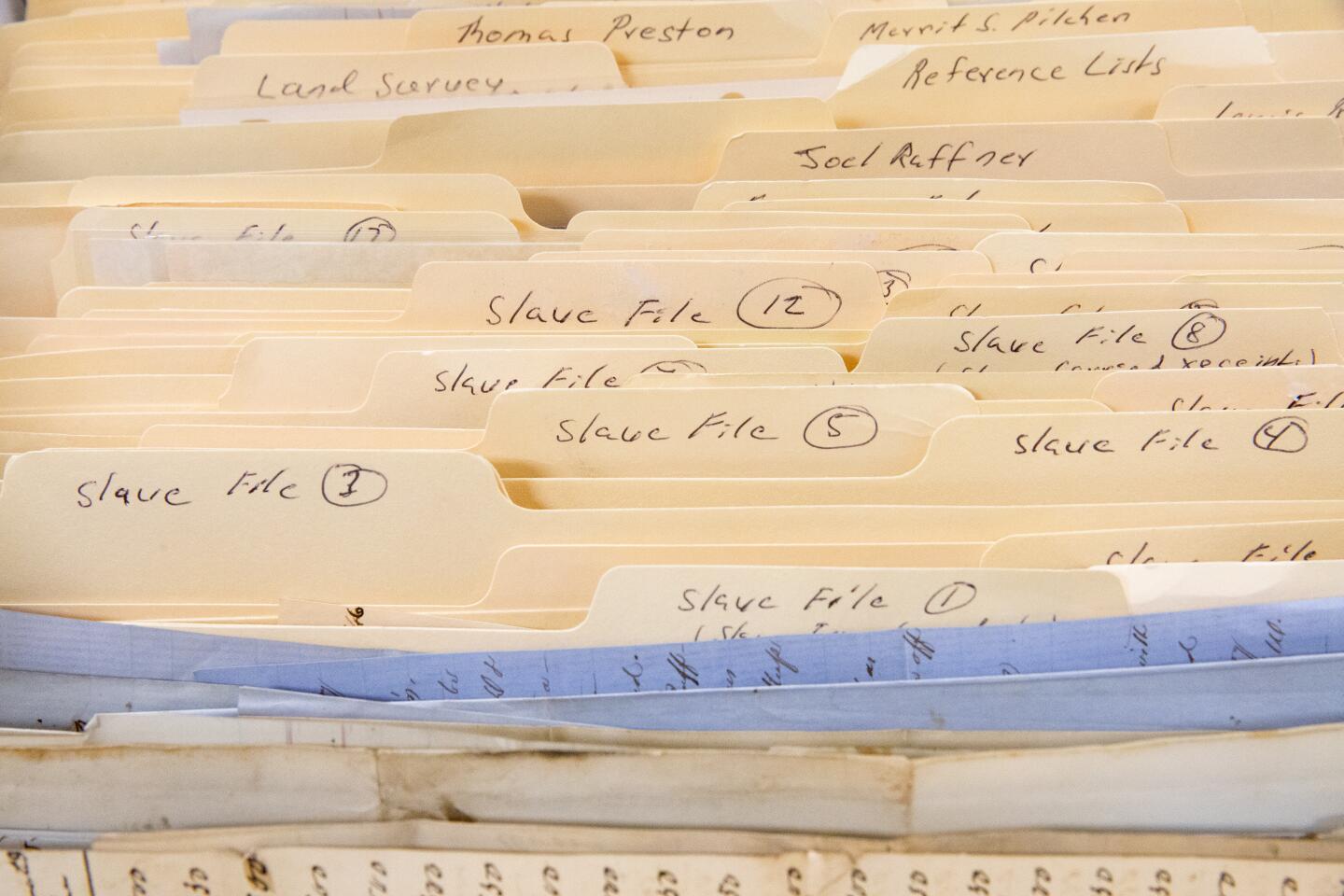

Nearly 2,400 miles away, another trove of documents acquired by the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, tucked neatly into four white cardboard boxes, illuminates a different aspect of the family business — its legacy of buying, leasing and selling enslaved black people.

In the fall, the Huntington purchased two collections related to abolition and slavery in 19th century America from New York’s Swann Auction Galleries.

One collection includes a rare account of the underground railroad from Quaker abolitionist Zachariah Taylor Shugart. The other, an archive of about 2,000 corporate records, documents the history of the West Virginia salt operation Dickinson & Shrewsbury from the early 1800s to the early 1900s.

Many of the records relate to the slave labor that fueled the business and the region’s salt industry.

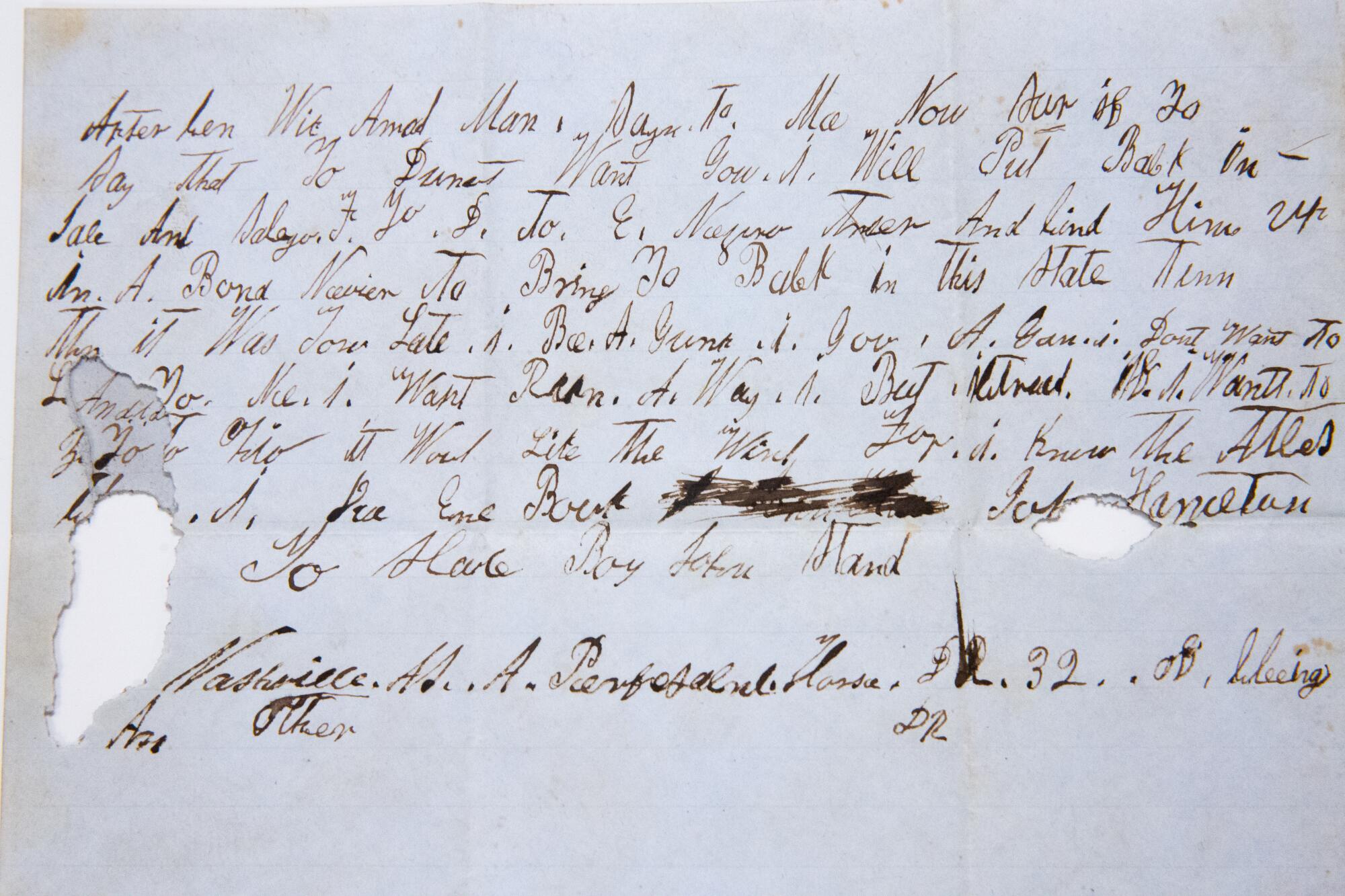

It includes correspondence between the two business partners in which slave labor was a constant and recurring subject, a handwritten letter from an enslaved person and inventories including the first and last names of enslaved workers owned or hired by the company. Other documents provide connections to Booker T. Washington, the post-Reconstruction era black leader, who lived near the salt company as a child.

Little is known about slavery in the salt industry, historians say. The product was essential to human life pre-refrigeration, used for preserving food, curing leather and dairy processing.

Thinking about slavery, “we tend to imagine plantations — cotton, rice, sugar, agriculture,” said Olga Tsapina, the Huntington’s curator of American history. “We don’t appreciate often how much slavery was worked into the very fabric of American society.”

Growing up in Charleston, Payne and Bruns said, the family didn’t talk much about its slaveholding past. The salt business wasn’t a topic of conversation either, added Payne, 49. “It was so distant that I didn’t really understand it until we got into this.”

Bruns, 53, spent the first half of her career in the food industry and began to take a closer look at the family business after her father died. She learned more about Dickinson & Shrewsbury from her then-husband, Carter Bruns, a historian who wrote his master’s thesis on the salt industry in West Virginia.

The Kanawha Valley region in the Charleston area was the largest salt producer in the U.S. before the Civil War. It attracted entrepreneurs hoping to make their fortunes off the product.

After Dickinson partnered with his brother-in-law Joel Shrewsbury, they began their salt-making operation around 1817. At its height in the 1840s, Dickinson & Shrewsbury had multiple salt factories and hundreds of enslaved people working on its property. When the partnership dissolved in the 1860s, the Dickinson family continued to make salt as J.Q. Dickinson & Co. until 1945.

Local attorney, politician and historian Larry Rowe refers to Dickinson and Shrewsbury as two of the four leading “salt kings” in his book, “Virginia Slavery and King Salt in Booker T. Washington’s Boyhood Home.” Today, Bruns and Payne run a much leaner operation with 10 employees at their revived J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works in Malden, about 10 miles from the state’s capital. Lined with flat white and pale houses, churches dating back to the mid-1800s and a general store, it’s a town where visitors can drive through in less than five minutes.

Paul Evans, 95, lives in a duplex about a mile from the saltworks. He worked for the company as a teenager, making 40 cents an hour sacking 100 pound bags of salt. “It was hard work,” he said. “Nothing real easy about it, just shoveling salt with a coal shovel.”

These days, things are different. Unlike earlier times when salt was churned out quickly, J.Q. Dickinson has a six-week process that involves solar evaporation. To augment the revenue of what is now a boutique operation, the company also hosts weddings, farm-to-table dinners and other events on the property.

On a recent tour, Bruns explained how her ancestors made salt.

It involved drilling deep into the earth to tap into the ancient and extinct Iapetus Ocean, which now produces salty water. The brine is boiled until the water evaporates and the crystallized salt residue is extracted, packed and shipped.

In the early years of Dickinson & Shrewsbury, before modern drilling technology, hollowed out trees were used to dig down and tap into the brine. “They put a man down in there with a bucket and shovel and he would dig,” Bruns said.

Calvin Grimm, a local filmmaker who spent two years researching slavery in West Virginia, added another detail. The men inside the hollowed out trees were often enslaved.

“They start digging and about 5 feet down, ice old water starts rushing into the hole and after about two minutes of being in that water, shock will set in and you die,” Grimm said. “At times, there were a couple dead slaves down in the hole.”

Even with technological advances, salt making remained a brutal job.

Enslaved people often worked 12 hours a day, in hot furnaces filled with smoke and chemicals, burning timber and coal. The region had the highest concentration of slaves in then-western Virginia (West Virginia became a state in 1863), and Bruns estimates that Dickinson & Shrewsbury had 500 enslaved workers over the course of its operation. About half were leased from plantations, often in eastern Virginia.

“There were regular explosions,” said historian Cyrus Forman, who grew up in the area. During the industry’s peak, there were “60 salt furnaces burning 24 hours a day, seven days a week … 3,000 enslaved people were working nonstop.”

The work was so dangerous that some slave owners took out life insurance policies that reimbursed them for financial losses if their enslaved workers died. Some companies that offered such policies are still around today, including Aetna and New York Life.

Kirk McKoy/Los Angeles Times)

The Huntington will spend months cataloging its Dickinson & Shrewsbury collection, for which the institution paid $173,000. Although it’s counterintuitive, Tsapina said, the institution has a rich archive of non-Western American history.

“Our collections on slavery, abolition and antebellum in the Civil War and Civil War-adjacent era is the third in the nation,” behind the Library of Congress and the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, she added.

Even with a small sampling of faded documents, Tsapina was able to add more context to how Dickinson and Shrewsbury viewed their enslaved workers.

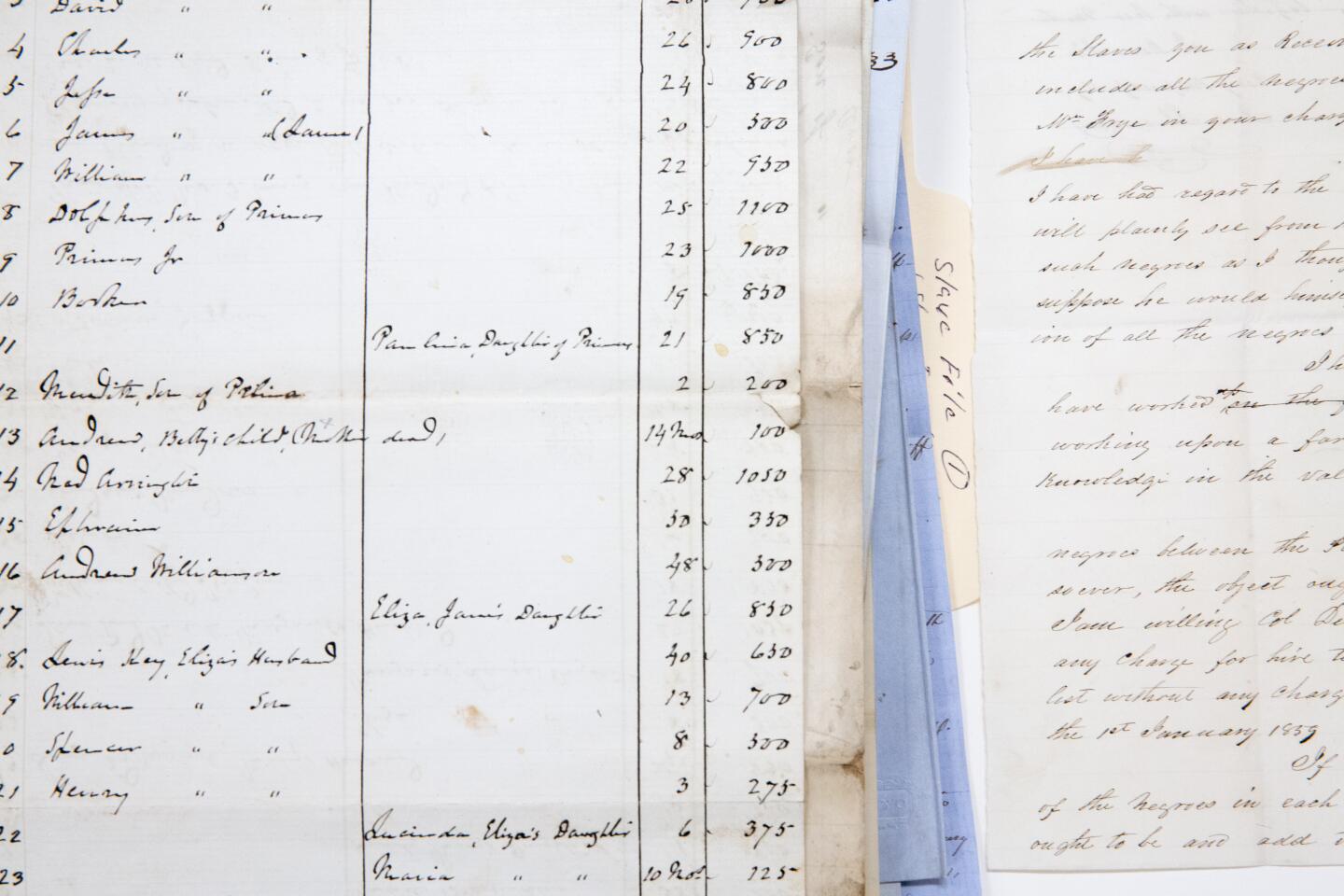

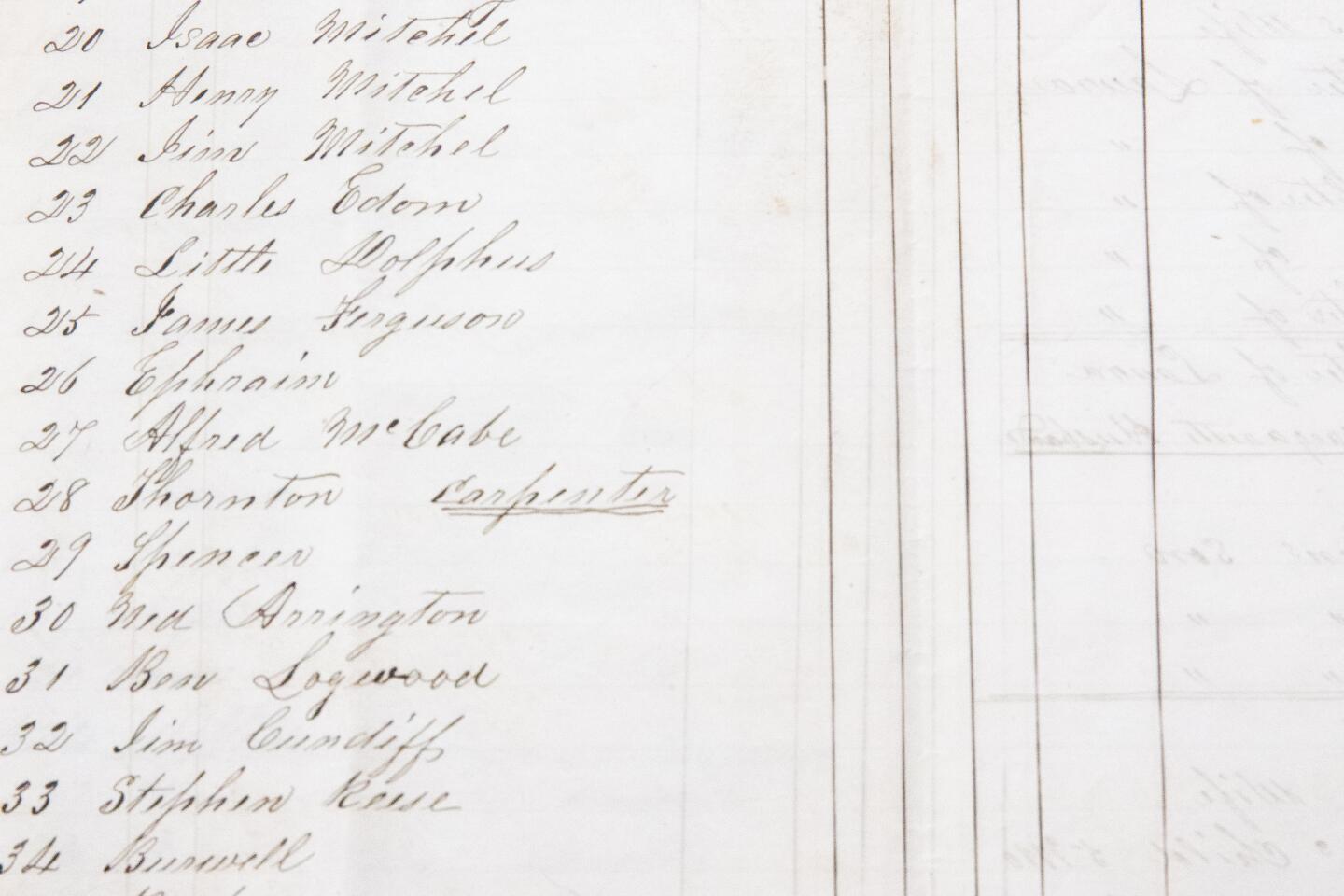

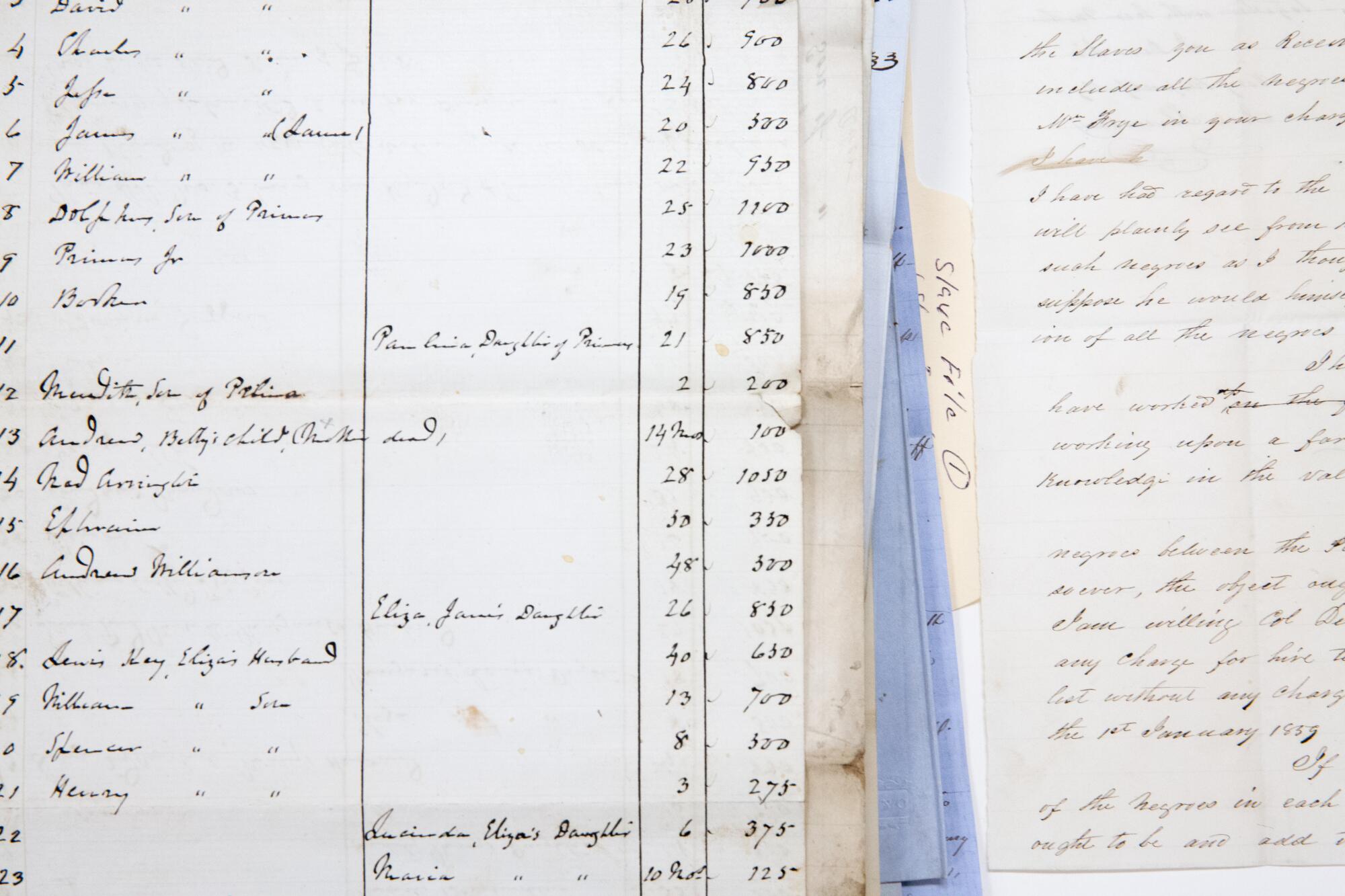

Tsapina removed a couple of documents from a file with her bare hands. (She clarified that using bare hands is safer than using white gloves to handle the fragile records.) One was an auction list from 1858 that included first and last names, ages and estimated values.

“Lot No. 3,” she read from the top of the page. “People were arranged in lots like cattle.”

“The company was breaking up. They were running sales because they needed to divide up the property between the partners.”

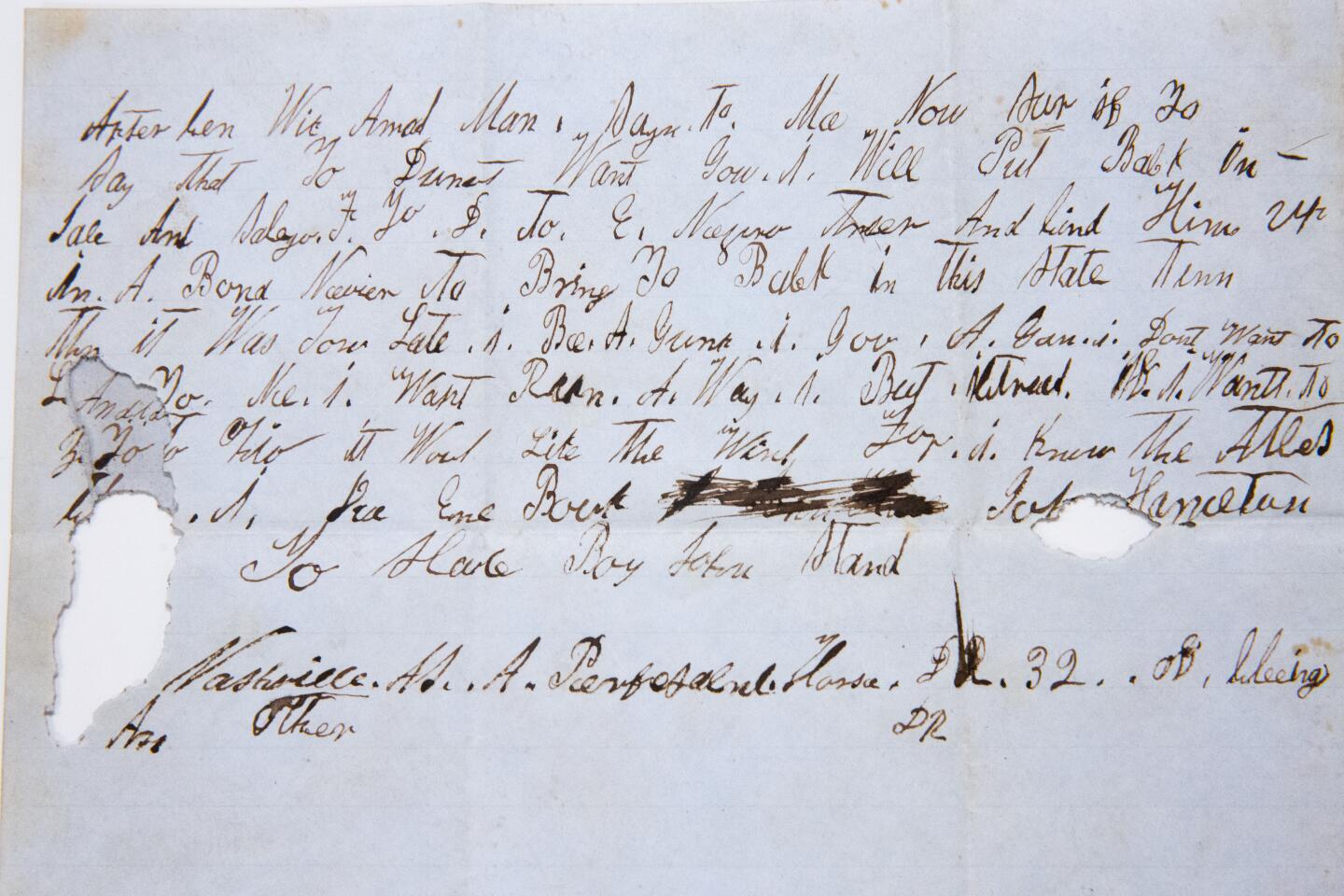

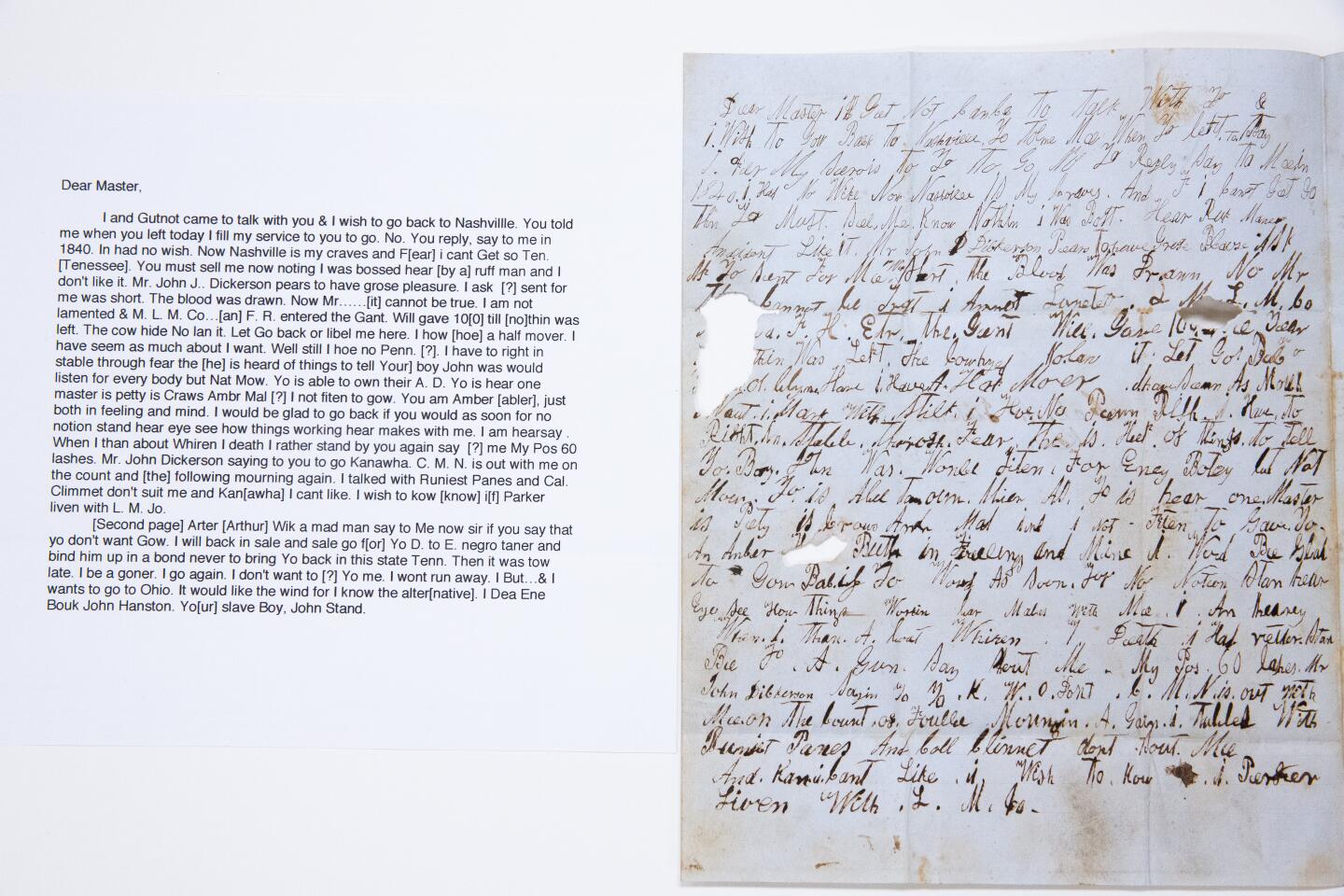

Signed “yo slave boy John Stand,” an extremely rare handwritten letter from an enslaved person is part of the collection. Although it’s hard to make out what the letter says, Stand expresses to Dickinson his wish to return to Nashville, Tenn., where the company had operations.

Slave labor was a regular topic in business correspondence. “The private letters were not entirely concerned with the welfare of the black folks,” Tsapina said. “If they are mentioned, it’s because they misbehave or run away.”

In one 1853 letter, Shrewsbury complains to Dickinson about a black woman named Mary, calling her “spoilt.” “If she cannot be made to know she is a Negroe & try to help herself,” Shrewsbury wrote, “she better die than to be the cause of 2 or more Negroes spoilt & run away.”

Hundreds of other letters and documents around slavery, including plans for slave hunts and inventories of slaves owned or hired by Dickinson & Shrewsbury, are part of the collection. One of the few printed documents is a runaway broadside signed by Shrewsbury offering $100 for “a bright mulatto man named William.”

Seeing just a couple of the documents was a surreal experience for Bruns, who with Payne first learned of the Huntington acquisition from The Times. During a recent interview, both were practically motionless as they studied the documents.

“It’s not something you want to know about your ancestors, but I guess that was the reality of the time,” Bruns said. “They were slaveholders and they were treated like property, not like human beings. It was disturbing.”

Inside the company’s shop, visitors can sample salt in flavors like wild onion and smoked bourbon barrel and purchase 1-pound bags for $28. There is no acknowledgment of the slavery that sustained the family business in the 1800s.

Bruns said a poster recognizing slave labor is in the old office building, where tour groups stop to learn more about the company’s history. The website includes a line on its history page timeline — in the 1830s, “most of the workers are slaves,” it says. Bruns also wrote a blog post acknowledging slavery in 2014.

In the company’s early days, she faced criticism for not acknowledging slavery in marketing materials.

“It’s delicate,” she said. “I do come from white privilege, but I didn’t make the decisions then and I’m open with whatever history I know, but I don’t think I need to have it in my advertisement.”

She hopes to learn more from the Huntington’s collection. “I don’t apologize for it, because it’s not my fault,” said Bruns, who added: “Acknowledging it and keeping it alive is important.”

How should companies reconcile with slavery in their past? It’s a question people are grappling with across the country.

Last year, wedding planning platforms Pinterest and Knot Worldwide changed their policies to stop promoting venues that romanticize former slave plantations after pressure from a civil rights advocacy group.

Georgetown University is among several academic institutions attempting to make amends for its ties to slavery. The school sold nearly 300 enslaved people to help keep the college afloat in the 1800s.

Historian Adam Rothman was part of Georgetown’s working group of faculty and students that studied how the school should make amends. As the group’s archivist, he digitized records about slavery to make them more accessible.

Institutions and companies have an obligation “not to hide the history,” Rothman said. “Whatever position you take on reparations, I think everybody can agree that it’s important to preserve that history and make the archival materials available to researchers.”

“I just think about how many other companies or families have archives that date back to that era of slavery with names of enslaved people in them and they’re sitting in a warehouse or attic,” he said. “That’s really precious information for a lot of people, just to know something about their own histories.”

For West Virginia, the Huntington’s acquisition is a missing puzzle piece to questions about slavery in the state. Documents like the salt company records are rarely available to the public — often lost, destroyed or hidden away in private collections.

“For 150 years, we’ve had a filtered view of slavery, I contend, led by Virginians talking about it being benign and good for the enslaved,” Rowe said. “The gaps in what we really know are just huge.”

The region’s history has been whitewashed, Grimm said. In downtown Charleston, the slaveholding salt industrialist families, including Dickinson and Shrewsbury, are used for street names.

But the Huntington’s collection could correct the narrative. “For the first time ever, people who still live in this area might be able to find their ancestors,” Grimm said.

He speculated that the well-preserved documents were willfully hidden so the family could distance its legacy from the horrors of slavery. (Bruns and Payne said they did not know of the documents’ existence, let alone who possessed them before the Huntington.)

Rick Stattler, the Swann Auction Galleries’ director of printed and manuscript Americana, said the collection’s source is confidential.

Generally, slavery records “can be cosigned directly by the original family, they could be from a collection that’s dispersed in an estate sale. … It could be from a collector who’s picked things up in various places over a long period of time,” Stattler said.

In 1850, California entered the union as a free state. But in that same decade, San Bernardino prospered with slave labor.

After cataloging the records, the Huntington will open the collection to researchers. Bruns and Payne hope they can also get access.

Payne recently obtained 501c3 status to preserve and archive the J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works collection. He’s working to convert the old office building into a museum.

Each year, the company also hosts a salt festival for the community. Bruns hopes a future festival can explore slavery and potentially create connections with descendants of enslaved workers.

It’s “an important part of the story that needs to be brought out into the light,” Payne said.

Acknowledging the history is important, said Kenneth B. Morris Jr., a direct descendant of Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington. Morris is also the co-founder and president of the abolitionist organization Frederick Douglass Family Initiatives.

“We’ve never had a point of reconciliation in this country around slavery,” he said.

He hopes that once more people in the community find out about the collection, they will “hold the company accountable, at least for acknowledging their slavery past. But then also what are they going to do to recognize and honor those they exploited to build their company.”

He quoted his ancestor Douglass — “agitate, agitate, agitate.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.