They lost their brothers to addiction. Now they’re tackling deadly stigmas head on, with humor

- Share via

When Stephanie Wittels Wachs introduces herself — to her daughter’s new first-grade teacher, for instance — it can be a little awkward.

“What do you do?” they’ll ask her.

For the record:

11:28 a.m. Oct. 22, 2020A photo caption in an earlier version of this story said that Harris Wittels died in 2017.

“I make podcasts,” Wachs replies.

“Oh, yeah? What’s your podcast about?”

“Um, death ...” Uneasy silence. “No, no, but it’s funny!”

There was nothing funny, of course, about the death that motivated Wachs’ podcast, “Last Day,” which premiered its second season Wednesday. Her little brother, Harris Wittels — a comedian, writer and guest performer on “Parks and Recreation” — died from an accidental heroin overdose on Feb. 19, 2015. He was 30.

Wittels’ death shocked and rattled the Los Angeles comedy community. His entertainment tenure was short but indelible: He coined the term “humblebrag,” and his chill, off-color, Phish-loving persona endeared him to podcast listeners as well as mentors and colleagues such as Sarah Silverman and “Comedy Bang! Bang!” host Scott Aukerman. He was set to play Aziz Ansari’s best friend in the Netflix series “Master of None” (the role was instead assumed by Eric Wareheim), and many of his famous friends grieved publicly and poignantly.

But it was a much deeper, more intimate loss for Wachs, who wrote her 2018 memoir, “Everything Is Horrible and Wonderful,” purely as an act of survival, says the 39-year-old mom of two. “I felt like I was dying of grief and pain.” She heard from many grateful, grieving people who told her they devoured the book in a single day — including Jessica Cordova Kramer, executive producer of the activist podcast “Pod Save the People.”

Kramer had just lost her own little brother, Stefano, to an overdose at age 34.

The two women connected online and quickly realized they were “soulmates from another dimension,” as Wachs put it. When Kramer, 41, met Wachs in person for the first time in February 2019, she realized not only that Wachs was “pocket-sized,” but also that together they could turn their very sour experiences into something semisweet. The result was Lemonada Media, which they formed from their home bases in Minneapolis (Kramer) and Houston (Wachs).

Drug rehabs across the U.S. have experienced coronavirus flare-ups or COVID-19-related financial problems, forcing them to close or limit operations.

Over a 24-hour “whiteboarding burrito session” at Wachs’ house in Texas (she now lives in Central California), they came up with a simple mission statement: “To make the hard things a little easier.” They self-funded the podcast network — employing help from their husbands, Wachs’ experience as a theater director and Kramer’s in nonprofit management.

Kramer proposed making their flagship show about the opioid epidemic, centered on one addict’s last day. Wachs was pregnant with her second child (a son she named Harry after her brother) and had no desire to talk about the smoldering crater in her heart. “But there was a thing in my body that was like: It’s wrong that opioids are killing more people than car accidents,” says Wachs, who persuaded Kramer to make Stefano the focal point of the series.

“Last Day,” which premiered in September 2019, tackles this national crisis through first-person storytelling. Opening with an on-the-ground re-creation of Stefano’s last day alive in Boston, it then gives way to interviews with his young widow and family — as well as policy experts, rehab specialists, doctors, recovering addicts and an expert in childhood trauma. Wachs treated the narrative as a manic investigative quest.

“There was a genuine curiosity and need on the parts of Jess and [me] to answer this question of ‘What could we have done differently?’” she says. “We’re educated. We’re tenacious. Our brothers were smart, they were successful, they died. Like, what went wrong?”

As host, Wachs reveals her own shifting paradigms about addiction and her lightbulb moments in real time. She also laces her intimate, gregarious, sometimes tearful narration with four-letter words. Empowered by having lost so much themselves, the duo wanted to make this “lemonade” with a balance of sweet and tart — to treat this stigmatized, misunderstood topic with a bracing irreverence and openness.

“We are members of the s—iest club,” Wachs says at the top of Season 1. “Our club may not have tote bags — which sucks — but Jess thought maybe we could have a podcast.”

Drugmaker Purdue Pharma launched OxyContin two decades ago with a bold marketing claim: One dose relieves pain for 12 hours, more than twice as long as generic medications.

“We thought our moms would listen maybe,” says Wachs. Instead, “Last Day” has had almost 4 million downloads and was the No. 1 global-trending podcast in February, according to Chartable. Though the first season ended in March, it’s still drawing 50,000 to 100,000 new listeners every month.

Wachs’ funny, acidic tone — combined with “This American Life”-caliber production values including original music by WNYC composer Hannis Brown — keeps the show from waxing pedantic. It gives listeners in bereavement, or struggling with addiction themselves, permission to ask uncomfortable questions, challenge received wisdom and laugh about their pain.

Kramer says she was flooded with emails asking: “Can you do something like ‘Last Day’ but for my issue?” “The way that Stephanie was able to talk about it in people’s ears,” Kramer says, “is like, ‘Oh, my God, if we could talk about x crisis or y issue that I’ve been working in for the past 20 years and I’ve been unable to get anyone to understand how complicated it is, that would be incredible.’”

As they were wrapping the first season, they decided to focus the second on a related crisis with rising rates: suicide. It presented a unique challenge to their “psychological autopsy” approach.

“When you find somebody who has a needle in their arm and they’re behind a bathroom door, you’re like, oh, that person overdosed — probably accidentally. Right?” says Wachs. “And we need to figure out how to make it so that person is not going to die.

“But it’s much more complicated with suicide,” she continues, “when there’s not a needle, when it’s not accidental, and you have to figure that part out. So I was interested in, from a storytelling perspective, how hard it is to talk about suicide. Because I love a challenge, and I love a Rubik’s Cube. And it is very inexplicable.”

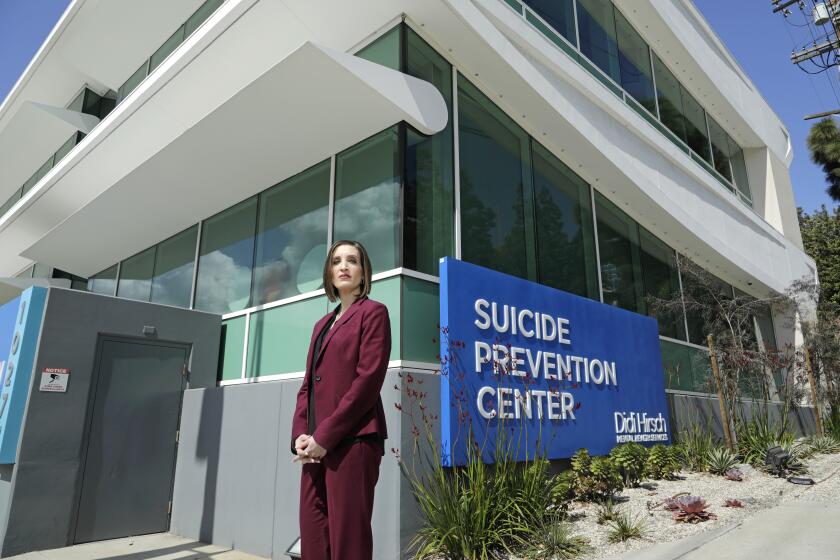

Crisis counselors at Didi Hirsch in Century City, whose job it is to reassure, now need some reassurance of their own — because the coronavirus knows no boundaries.

The 12 episodes of Season 2 take on this equally stigmatized demon — which has claimed victims from the elderly to veterans to families of those killed at Sandy Hook — with the same tone and storytelling approach, centering on a suicide intervention and its aftermath. Wachs and Kramer partnered with the Jed Foundation, a nonprofit suicide-prevention organization that sponsors the show, to make sure they don’t trip any of the many landmines surrounding this complex topic.

But they still wanted to ask all of the “wrong” questions, to interrogate conventional beliefs and misinformation. They discovered, for example, that growing research shows trigger warnings can potentially do more harm than good.

Lemonada has a full-time staff of 17, made possible by $1.38 million in seed funding raised this year. Other podcasts on the network fit the core theme, covering the “hard things” of body image, loneliness, parenting, bullying, immigration — and, unexpectedly, the pandemic. Andy Slavitt, a health executive in the Obama administration, was able to get “In the Bubble” up and running within a week in late March.

“The Untold Story: Policing,” a podcast about police violence against Black Americans, came together almost as quickly in July. As a whole, the network is closing in on 1 million downloads/listens per month.

“If our goal is to talk about hard things, and they keep happening, we have to be able to meet the moment,” says Wachs.

Not every Lemonada show has such a heavy brief. The network’s next entry is “Add to Cart,” a podcast about conscious consumerism with Kulap Vilaysack — who cohosted the comedy podcast “Who Charted?” from 2010 to 18 — and SuChin Pak, a former MTV News correspondent. They met last year in the Asian American and Pacific Islander breakout group of Time’s Up Entertainment.

“Add to Cart,” which premieres Nov. 17, offers “a subversive and fun way about talking about consumerism, and how we all participate in it — especially as Americans — more and more subconsciously and unconsciously than ever,” says Pak. “It was a way to talk about really intimate and personal things in our lives, and in other people’s lives, but through something that’s very accessible — like, what’s in your medicine cabinet? Or what’s the most embarrassing thing you bought during quarantine?”

Vilaysack was a close friend of Harris Wittels, and she connected with Wachs after his death when everyone was “just kind of clinging to each other and just trying to figure out the why,” Vilaysack recalls. “And I just came to love her. Steph introduced me to Jess, and I think Jess is so smart and so experienced, and she’s the type of woman I love — somebody who’s like a go-getter, makes things happen, has strong will.”

Kramer is spending time with her husband and children in Rome, where she speaks the language and holds dual citizenship. She’s there in part to launch an Italian Lemonada series.

It’s a country where podcasting is just getting off the ground, she says, and — with its challenges as an early COVID-19 hotbed in the north and a new front for the disease in the south — “a place where an infusion of hope will be a good thing.”

‘Can’t Stop Watching,’ ‘Asian Enough,’ ‘Legend of Sport’ and other podcasts by the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.