Commentary: Why finding mammy dolls at the Rose Bowl Flea Market was an unwanted reminder of racism

- Share via

During the pandemic, spending time at outdoor flea markets has become one of my favorite things to do. Before L.A. reopened and vaccines were widely spread, shopping outside felt safe. And having an excuse to dress up and buy things I probably didn’t need made me feel almost normal again. With my newfound love, I knew I had to check out the massive Rose Bowl Flea Market in Pasadena, which boasts more than 2,000 vendors and some 20,000 visitors every second Sunday of the month.

In July, I finally had that opportunity and was thrilled to shop for something unexpected. I thought I would find a fun summer outfit or unique jewelry. Instead my biggest surprise was the prevalence of racist, anti-Black memorabilia sprinkled throughout the market.

About 10 minutes after I entered, quickly scanning booths to see if anything caught my eye, I noticed a set of dark figurines lined up on a vendor’s table. “Are those mammy dolls?” I asked loudly, incredulously. I went to get a closer look.

They were not mammy dolls. With clownish red lips, ears pointing straight out, eyes fixed in a dazed stare and hands outstretched, the figurines were grotesque caricatures of Black men. Little white tags indicated that these rusted mechanical banks were really old — one was from the late 1800s — and expensive — some going for more than $300. Similar to a piggy bank, by placing a coin into the figurine’s hand and pushing a lever on the back, the caricatured Black man swallowed and stored money.

The longer I stared, the angrier I became.

“Why are you selling these racist things?” I asked, directing the question to the three men working the booth. After exchanging a look that I interpreted as annoyed, one of the vendors — a middle-aged Latino man in dark sunglasses — walked over to me. He said that people have been more argumentative with him about selling these items lately. (I explained that I was not arguing, just asking a question.) He said that the racist banks were a way of “preserving history.” He said that mainly educators and “African Americans” buy these artifacts. He said he had much more on another table to my left.

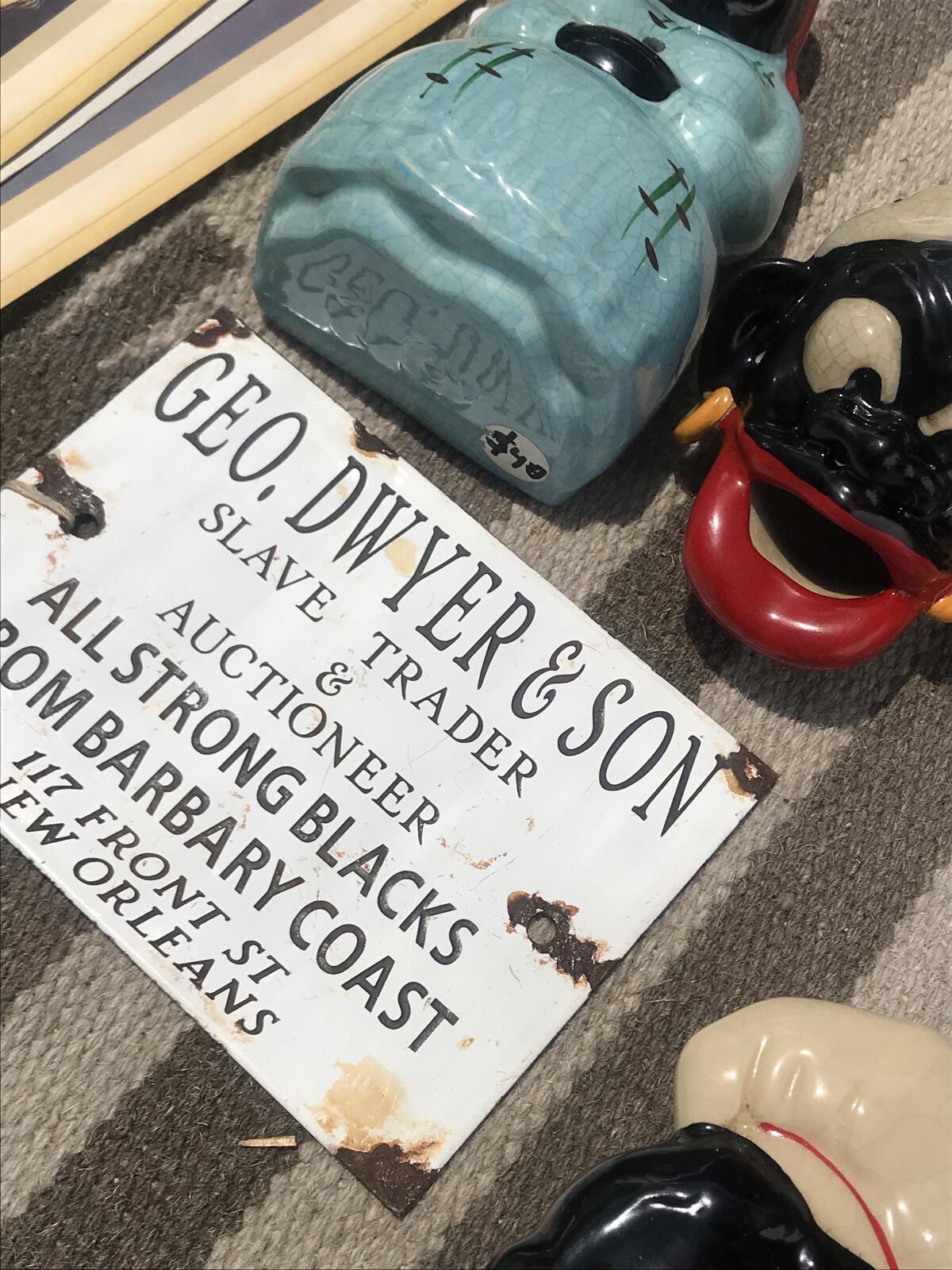

On the table sat even more hideous symbols of the violent racism and stereotyping Black people have faced in this country, including salt and pepper shakers carved into caricatures of Black men, mammy figurines and a sign for a slave auction company. I felt queasy examining the items and also thinking about the dealer making a profit from them. As my chest tightened looking, I noticed people nearby browsing the other antiques, seemingly unaware of the pain these objects conjured in me.

Eager to try and continue with my carefree Sunday, I moved on. But it wasn’t much later, before I noticed another set of racist, caricatured objects, including a life-sized lawn jockey-esque piece, obviously offensive children’s dolls and more mammy figurines at several vendor booths.

Near the end of my visit, I noticed yet another mammy. I was tired and ready to go home, but curiosity got the best of me. “Where do you find these?” I asked the middle-aged white woman, who was working the booth. She said they come from all over. When I told her the mammy was upsetting to see, she gave a similar line about preserving history and educating young people about racism and the atrocities of the past. In addition to the mammy and other antiques, I also noticed an anti-Asian bottle opener. I was over it.

When I returned home, I immediately started researching what I had just encountered. Those mechanical banks? Although one tag just referred to it as a “bank,” their official title is “Jolly N— Banks ,” which were first created in the 1800s. The children’s rag dolls? They’re based on a story book character called Golliwog, a Black minstrel doll. I learned some of the figurines I saw were based on the coon caricature, created during slavery, which depicts Black people as lazy and idiotic. I already had some knowledge of the mammy caricature, which depicts Black women as content in their servitude, but didn’t realize the prevalence of the imagery, which has appeared in popular culture — think Hattie McDaniel’s Mammy in “Gone with the Wind” and Aunt Jemima — but also on ashtrays, fishing lures, string holders, detergent and kitchenware.

I’m no performance artist, but I had vivid visions of “accidentally” dropping and smashing those racist objects in plain sight of the dealers.

After sharing my experience on Twitter and Instagram, friends and strangers reached out, equally disturbed by what I had encountered at the Rose Bowl Flea Market. “In all my many times of going, I’ve never really noticed,” wrote one friend in a direct message. “Or maybe it’s because I just go for the clothing and get lost in that section, but this is sick!”

In an effort to understand why the Rose Bowl Flea Market allows its vendors to sell racist memorabilia, I reached out to Dennis Dodson, chief operating officer of R.G. Canning Attractions, which launched the event in 1968 and runs markets in Beaumont and Ventura.

“We’ve come across a lot of this stuff over the years,” Dodson said. About 20 years ago, the company faced a lawsuit from a customer upset about a vendor selling a Nazi flag. The judge ruled in favor of the event company because of the First Amendment, Dodson said.

After the lawsuit, R.G. Canning worked with the Rose Bowl operating committee to change its vendor rules. Now, vendor permits say that the company can remove items it finds objectionable, “keeping in mind that we have 2,400 vendors, and it’s hard to see every little thing,” Dodson said.

During the monthly events, a team patrols the grounds, looking for counterfeit and other questionable items and responding to complaints from customers. He said that if I had noted the booth number and vendor name and made a call on the Sunday I attended, someone from the team would have inspected the items.

“When we see these vendors with stuff that we call — some people call it — objectionable, another person will call it history, so it’s kind of a borderline. If we think it’s objectionable, we’ll just plain ask them to put it away.”

I asked Dodson how “objectionable” is defined. Judgements are made on a case-by-case basis. Playboy magazines, “the ‘N-word,’ the ‘F-word’ or a Nazi flag” are out of line, Dodson said. “Even Confederate flags are out of taste right now.”

So is anti-Black memorabilia, he added, saying that he’d seen my tweets. “We really don’t think this is in good family taste, especially right now with Black Lives Matter being such a big issue.”

I also asked Dodson about the things he’d seen that crossed the line in his more than 50 years being involved in the flea market. “Usually it’s the flag, and a lot of times it’s a flag on the ground,” Dodson said. “It could be any foreign country, any country — a flag on the ground is to me unacceptable.”

To learn more about what it’s like to actually collect these painful artifacts as an educator, I reached out to David Pilgrim, the founder and director of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University.

The museum, which began with Pilgrim’s personal collection of 2,000 items, now houses about 18,000 artifacts spanning the Reconstruction era, the segregation era, the civil rights movement and beyond. Many of the objects in the museum are cruel, anti-Black caricatures — not unlike what I encountered at the Rose Bowl Flea Market.

Pilgrim, who is Black, began collecting items that belittled Africans and their descendants in the 1970s in Alabama. He began with a mammy saltshaker, and over the years, he’s collected racist children’s games and musical records with racist themes. In building his collection, he’s also encountered horrifically violent objects including lynching post cards and a puzzle game first manufactured in 1874 called “Chopped Up N—s.”

In the past, Pilgrim would end up in “really ugly conversations” with dealers about the objects they were selling. “It was counterproductive, because I was trying to collect stuff to document the atrocities of the past, but all I was getting was the argument,” he said. “I had to find some level of detachment in order to do what I thought I needed to do.”

Anti-Black memorabilia is a powerful teaching tool, Pilgrim said. It’s a way to show people how everyday objects portraying Black people as subhuman were used as a form of social control, both reflecting and shaping attitudes in society.

Pilgrim wasn’t surprised that I found numerous racist items at the Rose Bowl Flea Market. “As a matter of fact, for a flea market of that size, I would have been really surprised if you hadn’t,” he told me. “Flea markets, along with what you might call internet flea markets like eBay, are really the primary way that these objects are sold these days.”

In Pilgrim’s experience, the argument from dealers that selling these objects is about preserving history has always “rang hollow.” “Because in almost every instance in over four decades of collecting where the person used that argument, they were selling a reproduction,” he said. And while there are Black people who purchased these artifacts as a way to document the past, most collectors were in it for the money, “because those original pieces from the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s had escalated in value.”

Filmmaker Chico Colvard’s 2018 documentary “Black Memorabilia” dives into collectibles culture and explores how some of the racist memorabilia being traded at flea markets are still being replicated at factories abroad.

While Pilgrim doesn’t believe it should be illegal to sell racist artifacts, “my work is about making it so there would be no demand, so that folks would recognize the harm that are done by these objects.”

I wondered if the so-called “racial reckoning” across the arts and preservation communities had any impact on collecting these objects and if dealers might have greater awareness about the pain selling these items could cause.

Pilgrim doesn’t believe it has.

“On one hand, some people become more aware, and they’re more sensitive to the presence of those pieces and they’re more likely to challenge folks who are selling it,” Pilgrim said. “But the flip side, there are all these new racist objects that are being produced as expressions of political freedom or being a maverick or being politically correct, so I think it’s probably a wash.”

Pilgrim, who said his experience collecting has never been pleasant, also looks for items that document racism in the present. Recently, while browsing a booth selling Donald Trump paraphernalia, he came across an object he couldn’t stomach — an election yard sign that said “Joe and the Hoe Must Go.” “In all the years that I collected, that was the first time that I just could not make myself give that guy $20,” Pilgrim said.

My experience forced me to think about whether or not these items should have a place at an outdoor market. I believe that they are a useful teaching tool, perfect for a museum or classroom setting. But a surprise encounter with racist, anti-Black memorabilia was immediately triggering for me, adding a stain on a day I wanted to use for rest, and made me feel that I didn’t have a place at the Rose Bowl Flea Market. To me, it crossed a line.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.