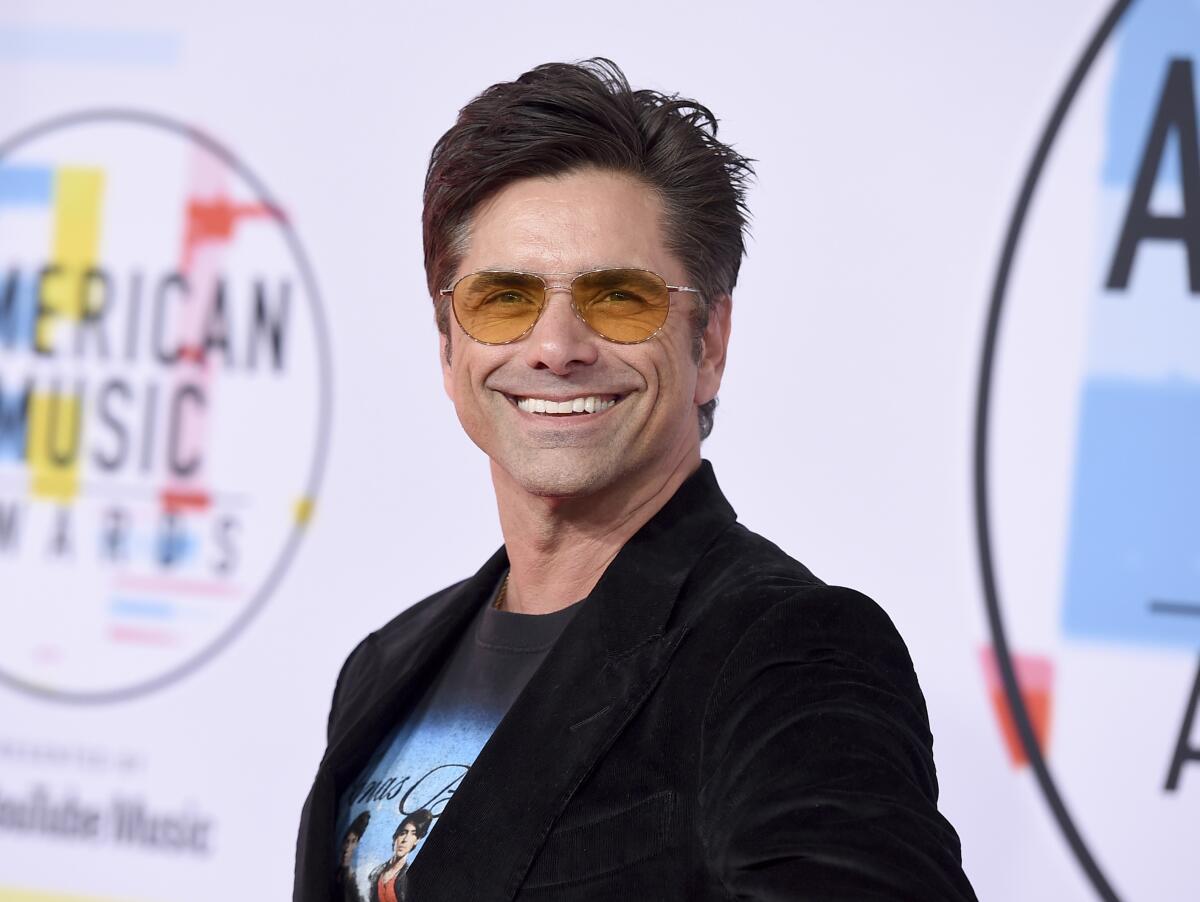

John Stamos’ Sinatra-kidnapping podcast is so wild that ‘you can’t believe it’

- Share via

John Stamos has been flexing new muscles lately — his podcasting muscles.

The actor and musician is narrator of “The Grand Scheme: Snatching Sinatra,” a multi-episode series that hits Wondery and all podcast platforms Tuesday after premiering ad-free earlier this month on Wondery+.

With it, Stamos finally brings to fruition the story of Barry Keenan, one of the men who kidnapped Frank Sinatra Jr. in 1963 when the son of legendary singer Frank Sinatra was 19.

It’s a tale that Stamos, star of the new Disney+ teen comedy “Big Shot,” got access to in an only-in-Hollywood kind of way. And he has been sitting on it for decades.

“I mean, this story is — you can’t believe it,” Stamos said in an interview last week.

With “Big Shot,” on Disney+, the “Full House” veteran has found the perfect part in a lovely show. Perhaps the Stamossance is already here.

The former “Full House” star said he was in his mid-20s and about to play an encore with the Beach Boys at the Orange County Fair when he was approached by Dean Torrence of the 1960s surf-rock duo Jan and Dean. Torrence asked Stamos if he ever produced anything. “I didn’t,” Stamos said, “but I told him yes.”

“He said, ‘Well, my friend, my best friend, kidnapped Frank Sinatra Jr. in the ‘60s, and I have this manuscript that he wrote in jail.’”

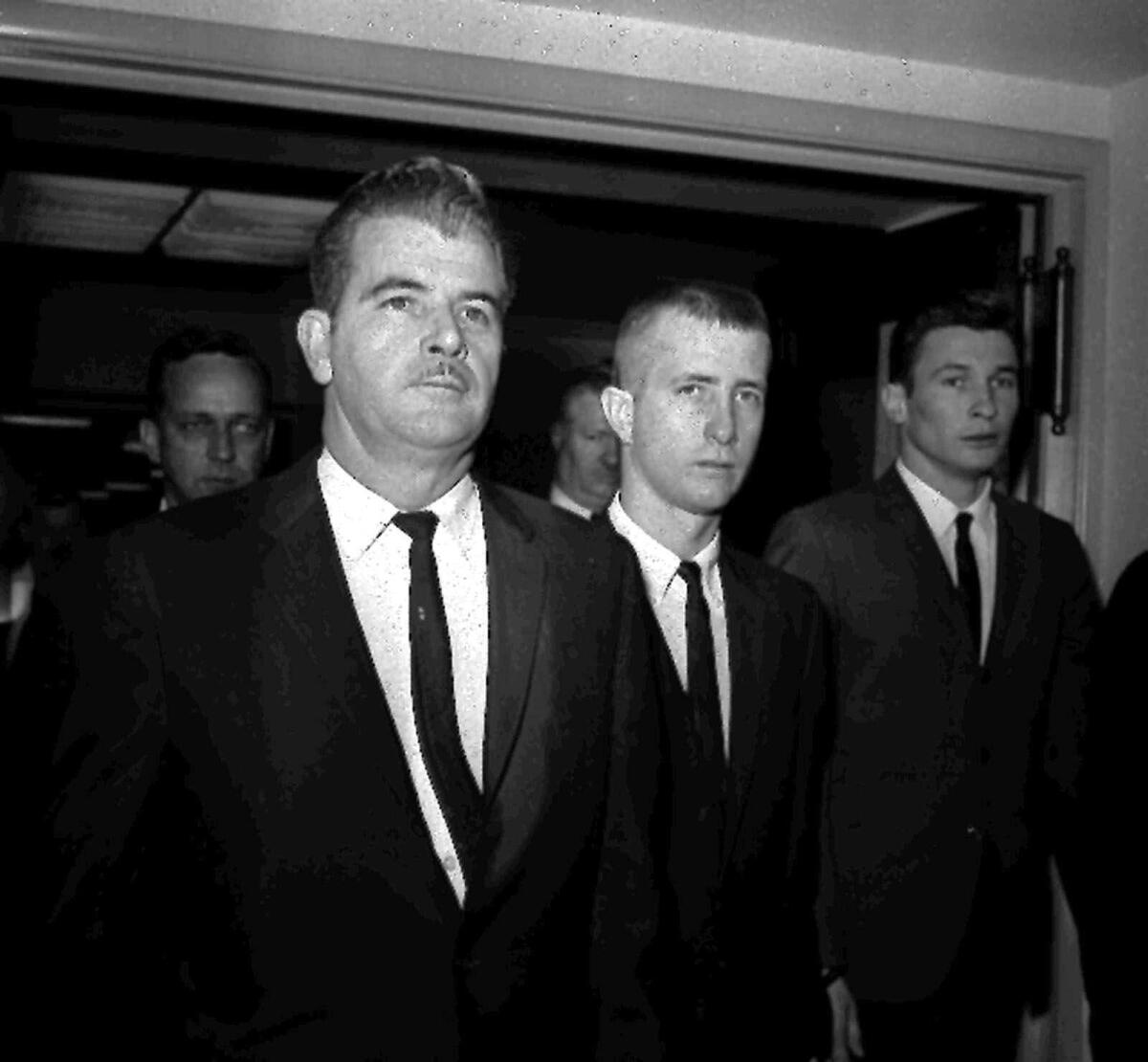

Torrence had apparently loaned Keenan some money over the years, and to pay him back, Keenan gave him what he had written while in prison, detailing the kidnapping that put him behind bars. Keenan masterminded the whole thing along with Joe Amsler and John Irwin. All three were convicted.

Stamos took the document and “just threw it in a box,” he said, because at the time he didn’t know how to proceed. Turns out the elder Frank Sinatra wasn’t a fan of the story.

“He didn’t want Barry to tell the story, and he put a number of hits out on Barry,” Stamos, 57, alleged over Zoom right before sharing video of himself interviewing Keenan, who was talking about one of the alleged attempts on his life.

“The guy who was shooting at me on the beach, in Huntington Beach. He had me dead to rights in his scope,” Keenan said in the video, “and his colostomy bag broke and caused him to miss me. He fired off a couple more shots, the sand popping up in front of me, so I just ran.”

The children: Frank Jr., rather than sisters Nancy and Tina, was the offspring most directly eclipsed by his father.

“That was the third attempt on him,” Stamos said.

The kidnapping had been embarrassing for both Sinatras, especially after it was over and Junior was accused of setting it up for publicity. Later, the younger Sinatra would say, “This family needs publicity like it needs peritonitis.” The elder Sinatra passed in 1998, while his son, also a singer, died in 2016 while on tour.

Keenan, who later had a career as a real-estate developer, actually struck a deal with Sony Pictures and Columbia Pictures in 1998, selling them the rights to his story. The younger Sinatra sued to stop the deal, arguing that perpetrators should not profit from their crimes.

In 2004 Showtime presented “Stealing Sinatra,” a semi-comedic dramatization of the kidnapping, which in real life included a $240,000 ransom payment for Sinatra Jr.’s safe return.

Frank Sinatra Jr. has filed a lawsuit to stop the men who kidnapped him 34 years ago from collecting a portion of a reported $1.5 million for movie rights to the story of his ordeal, his lawyer said Monday.

Stamos said of the kidnapping story, “I always say it’s like the Marx Brothers meet the Coen Brothers, where it was wacky, but the truth was, this was a mentally ill man who — this was not funny.

“I mean, I have a son. The idea of someone kidnapping him is not funny,” he said. “So I wanted to dig into his psyche and figure out why.”

Stamos is genuinely intrigued by Keenan’s story, which includes bizarre twists and turns, is complicated and weird, and has that trendy true-crime element. Although Keenan, who’s now 81, was sentenced to life plus 75 years behind bars for the kidnapping, he was released after only 4 ½ years after it was determined he hadn’t been legally sane at the time of the crime.

Joe Amsler, 65, one of three men who kidnapped Frank Sinatra Jr. in 1963, died May 6 in Roanoke, Va., of complications from liver disease, family members said.

“To be brutally honest, I’ve been trying on all fronts to get the story out,” Stamos said, “and I’m still going at it and I’m gonna get it done.”

He’s done it already, of course, through the podcast. But that’s not enough for the entertainment veteran, who’s been pitching it as a limited series as well, a la “Dirty John,” the Los Angeles Times story and podcast by Christopher Goffard that was turned into a series for Bravo.

“The thing that was appealing to this was that this story, it takes a lot — you can’t do it in a movie, you know,” he said. “I’m out pitching a limited story to some good people, but it takes time.”

“This guy’s life, you have to go back to his childhood ... you realize that he was mentally ill,” Stamos added. “He was hearing voices, and he turns to his aunt, who was Catholic, and he was Catholic, and said ‘I’m hearing these voices,’ and she said, ‘Don’t tell anybody, assimilate,’ and that’s what he did his whole life.”

At the time of the kidnapping, Keenan and Sinatra Jr. were both practically kids. The latter was starting out on a singing career, and the former was a frustrated young guy who “wanted a seat at the big table,” Stamos said, “and he was going to do anything he could to get there.” Keenan had also been obsessed since a young age with getting into heaven.

Then one night, at the lowest point of his life, Keenan was sitting on Balboa Island in Newport Beach when, according to Stamos, “He said God’s voice came over the radio and told me how to get out of this” — by kidnapping Sinatra’s son. “And the radio wasn’t even on.”

Jim Mahoney believes he’s stumbled on the rarest of rarities: two unreleased Frank Sinatra songs. Experts aren’t so sure. You can decide for yourself.

The podcast takes that story and runs with it.

Making “The Grand Scheme,” which was produced by Spoke Media in collaboration with Wondery, used “a different muscle” for Stamos, who has done series TV for decades as well as acting in multiple shows on Broadway.

“It’s not like acting,” he said. “I really had to have people trust me to take them on this long journey.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.